1.6 — Consequences & Sources of Power

ECON 306 • Microeconomic Analysis • Fall 2022

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microF22

microF22.classes.ryansafner.com

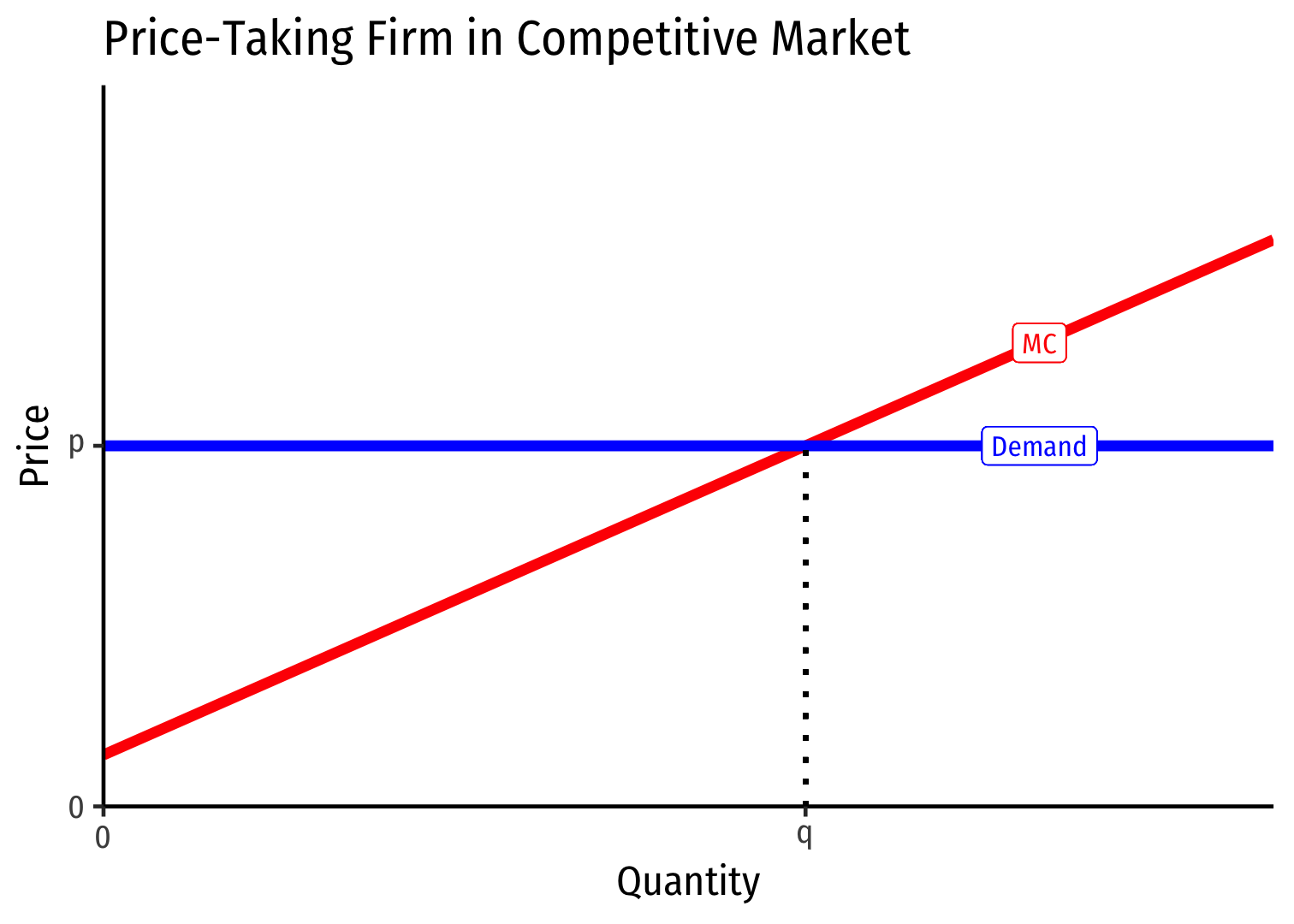

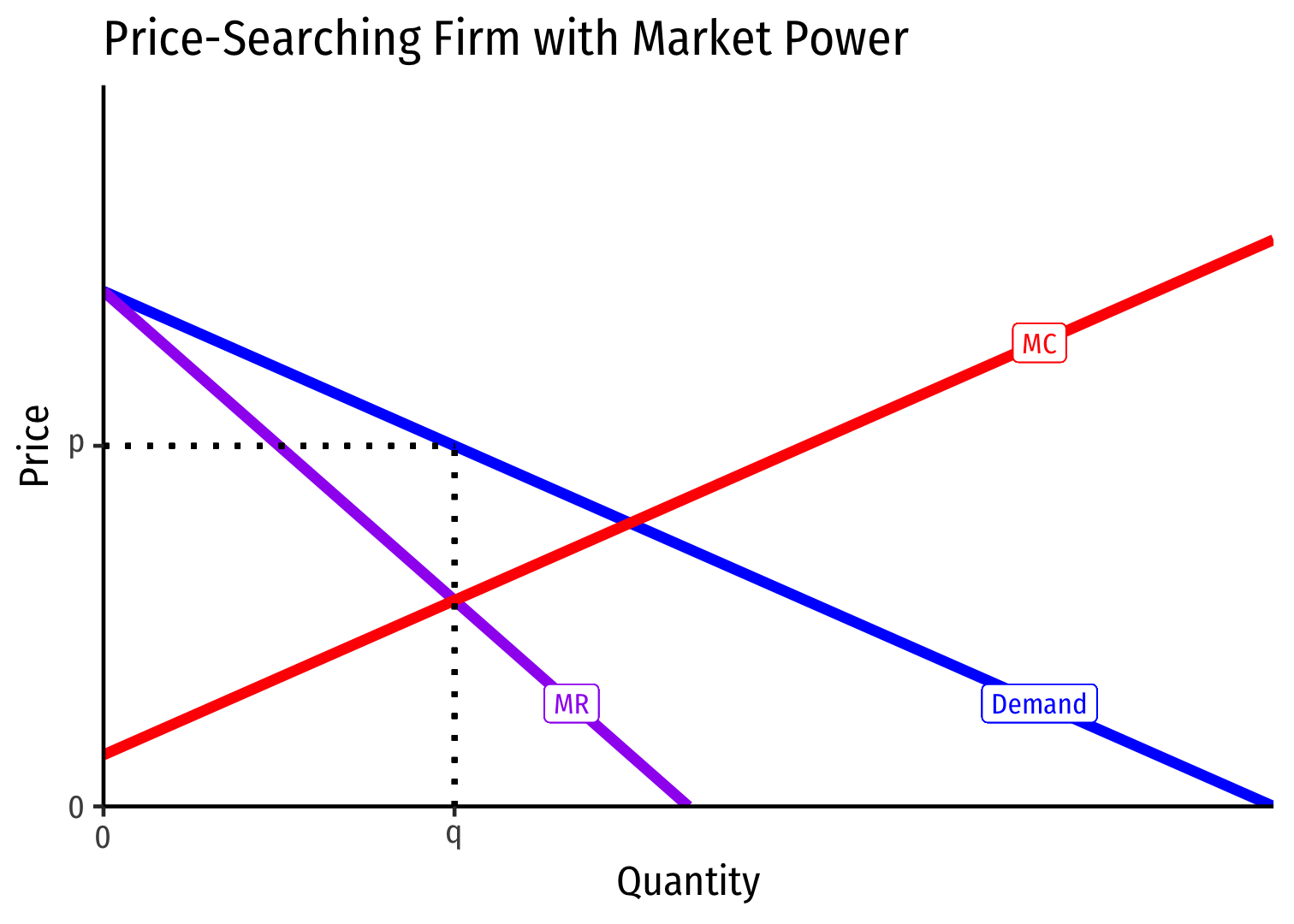

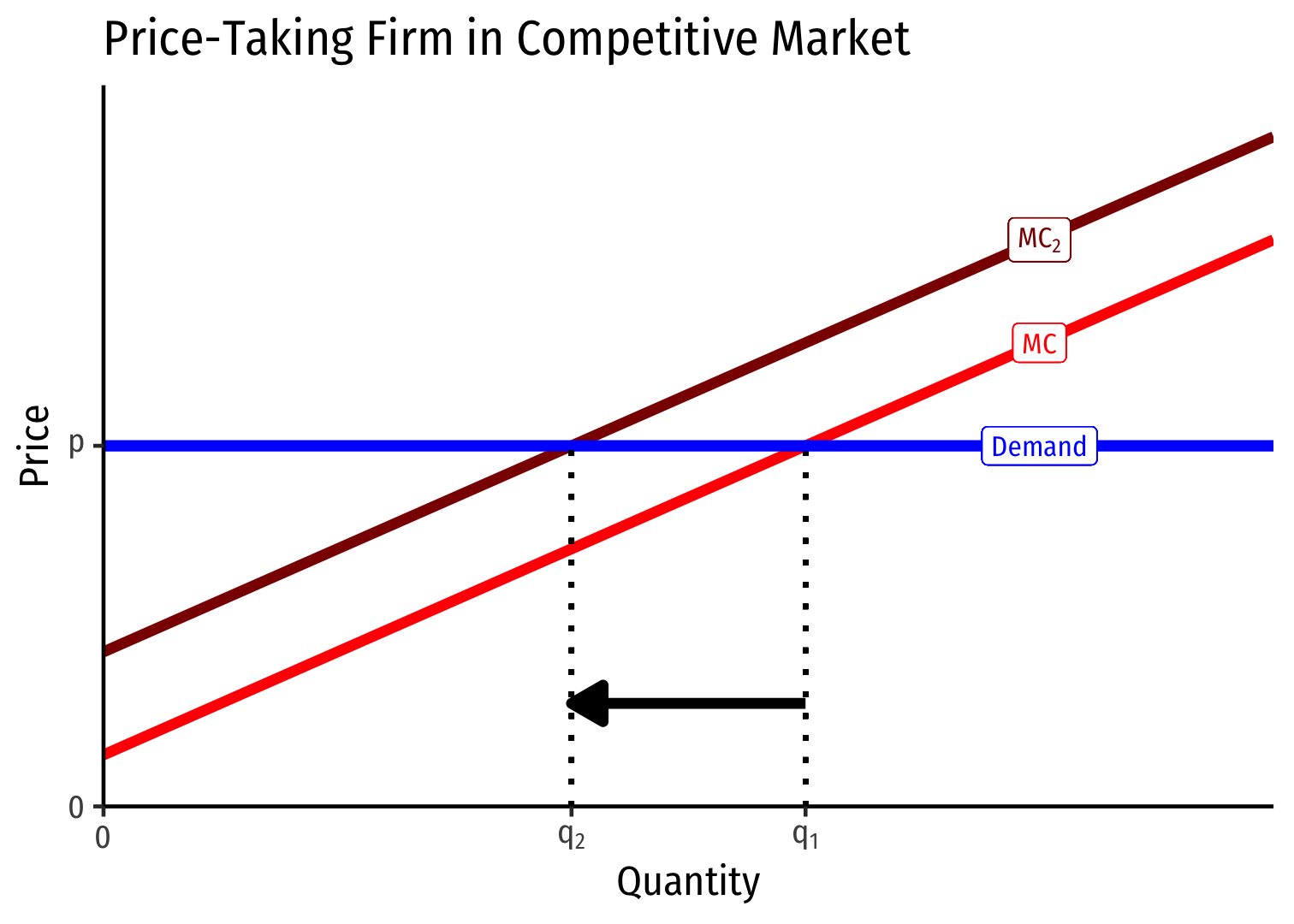

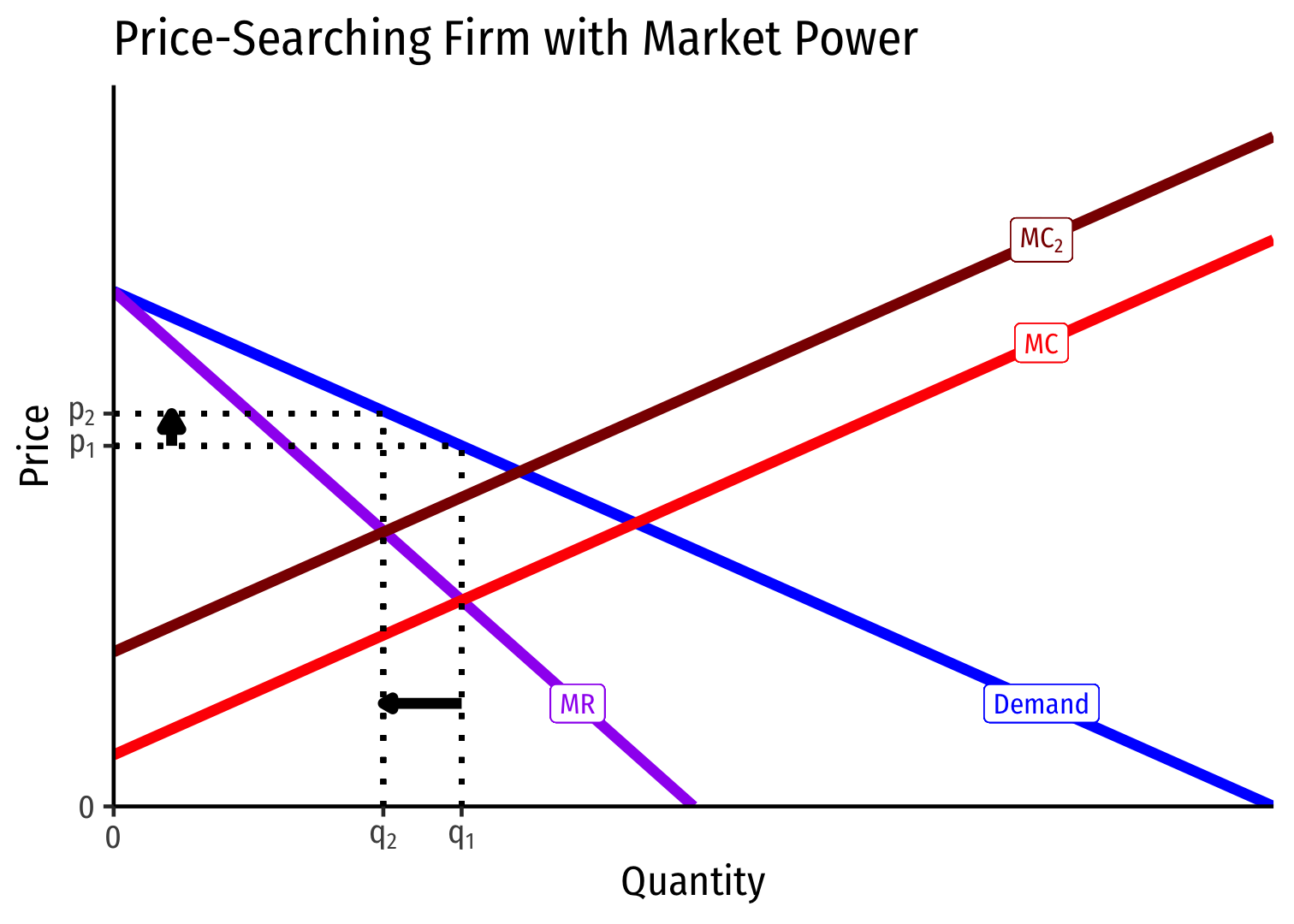

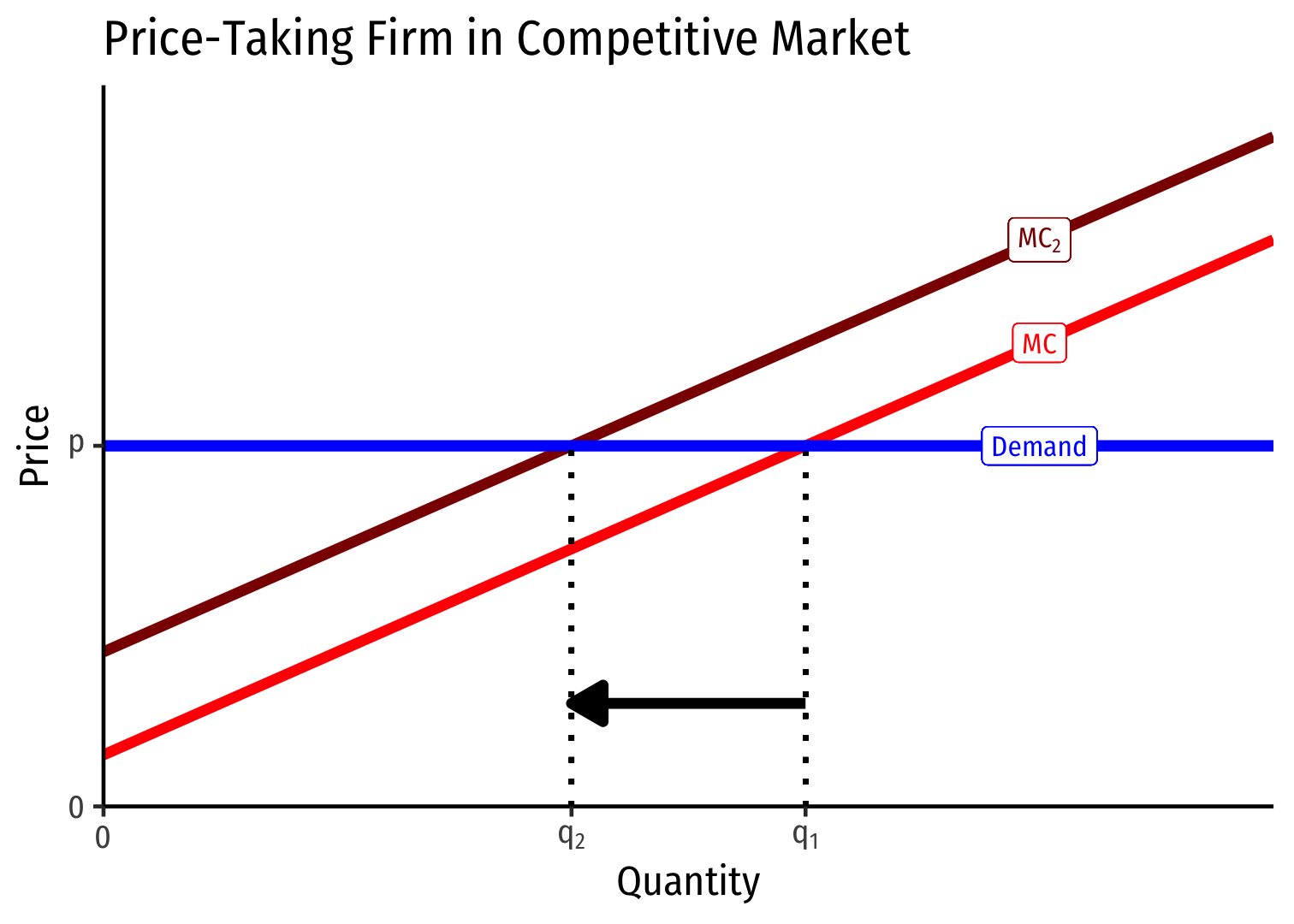

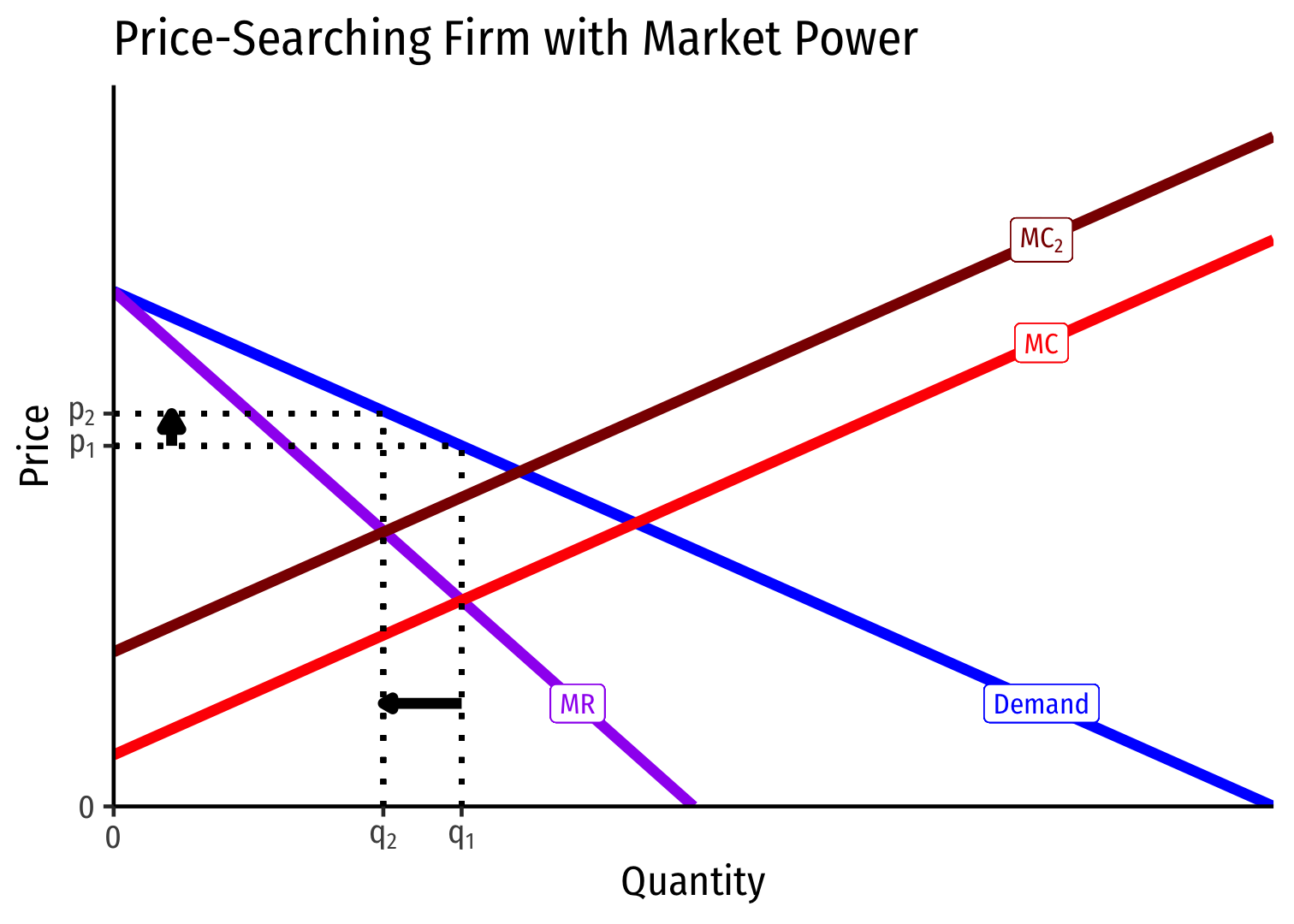

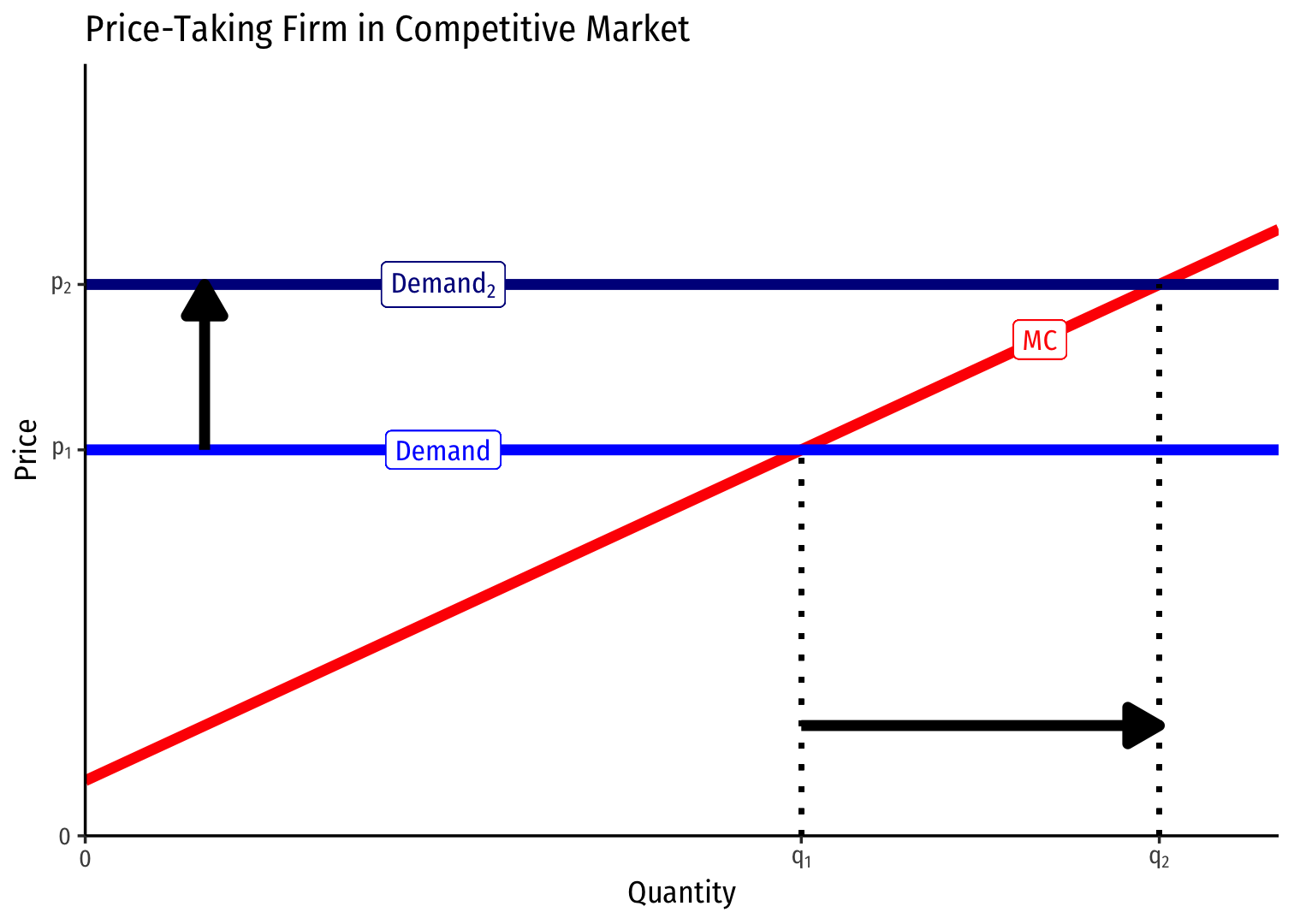

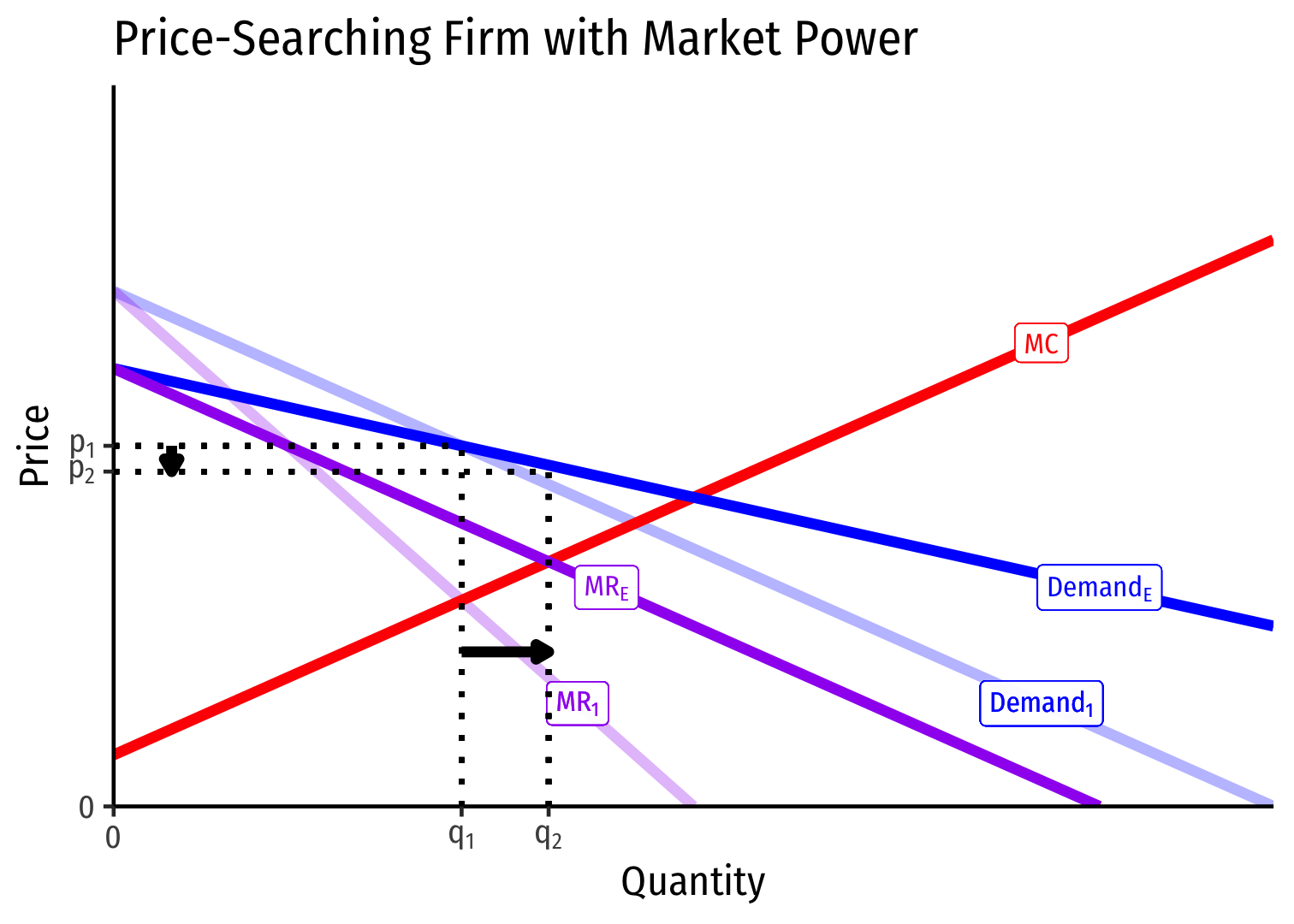

Comparative Statics: Differences In Firm Behavior

Firms With Market Power Respond Differently

A Change in (A Firm’s) Marginal Cost

- Change in q⋆ only

- Change in p⋆ and q⋆

A Change in (A Firm’s) Marginal Cost

- Change in q⋆ only

- Change in p⋆ and q⋆

- Firms with market power will pass on cost increases (from e.g. taxes, etc.) onto customers, competitive firms will not

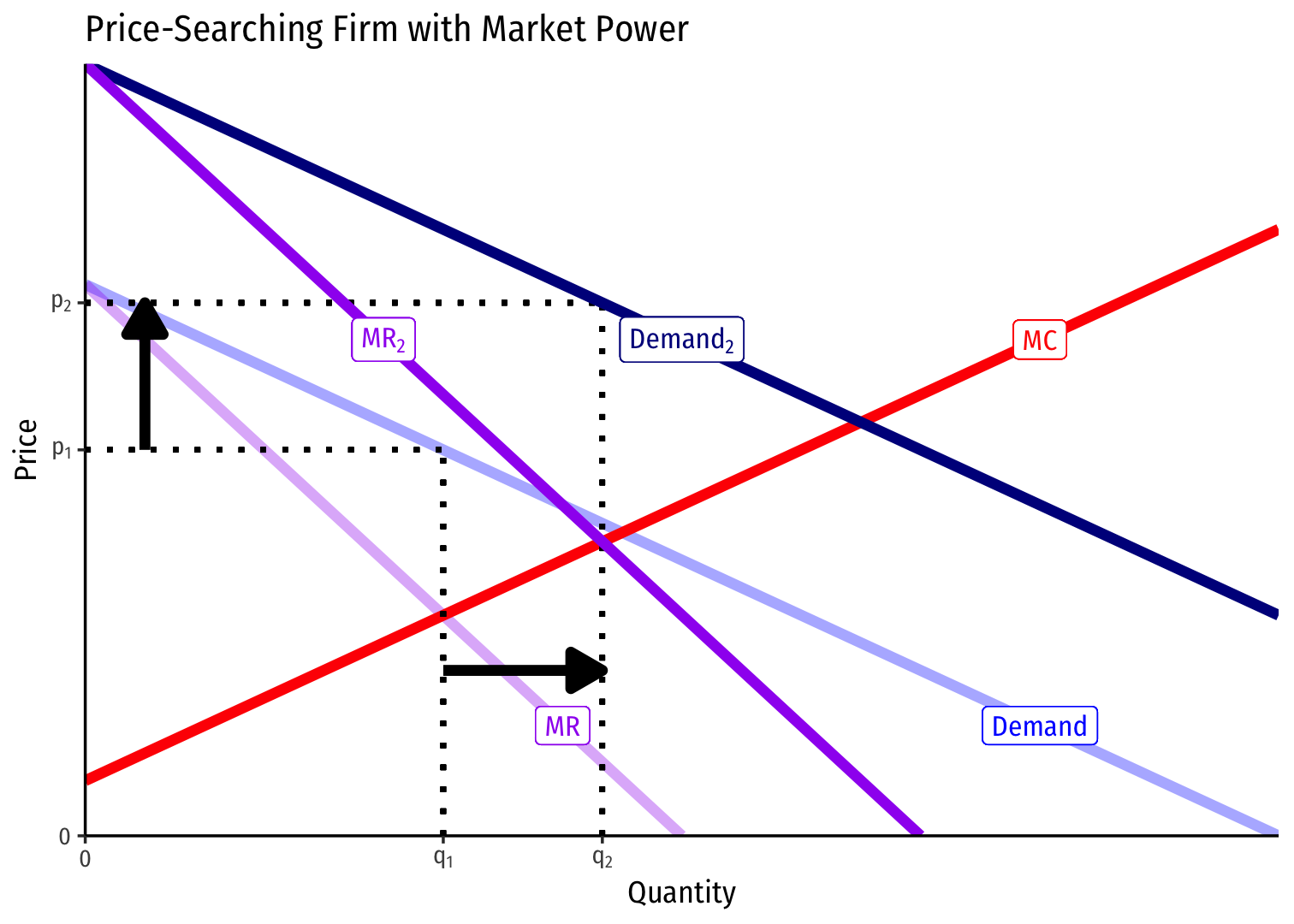

A Shift of Market Demand

- Both firms change p⋆ and q⋆, but smaller change in q⋆ for monopolist

A Change in Price Elasticity of Demand

- No change in q⋆ or p⋆ for the industry!

- Monopolist will lower (raise) p⋆ and raise (lower) q⋆ as demand becomes more (less) elastic

Market Power: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

No market is perfectly competitive, but that does not necessarily imply market failure

- Static vs. dynamic benefits of markets

Market power is interesting

- Most firms clearly have some market power

- Market power ≠ bad, necessarily!

Today, we’ll examine what I call “the good, the bad, and the ugly” of market power

- (but not necessarily in that order)

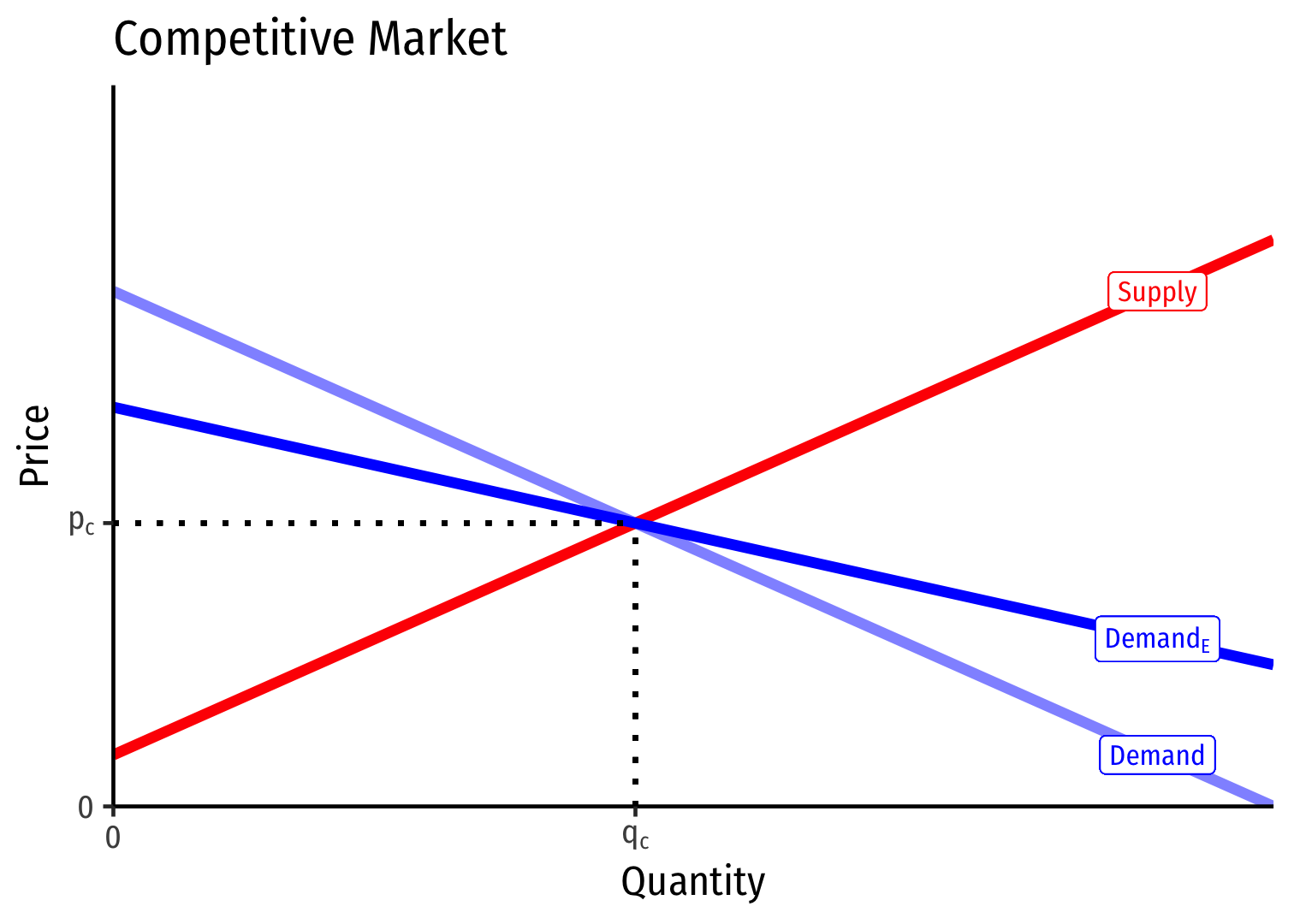

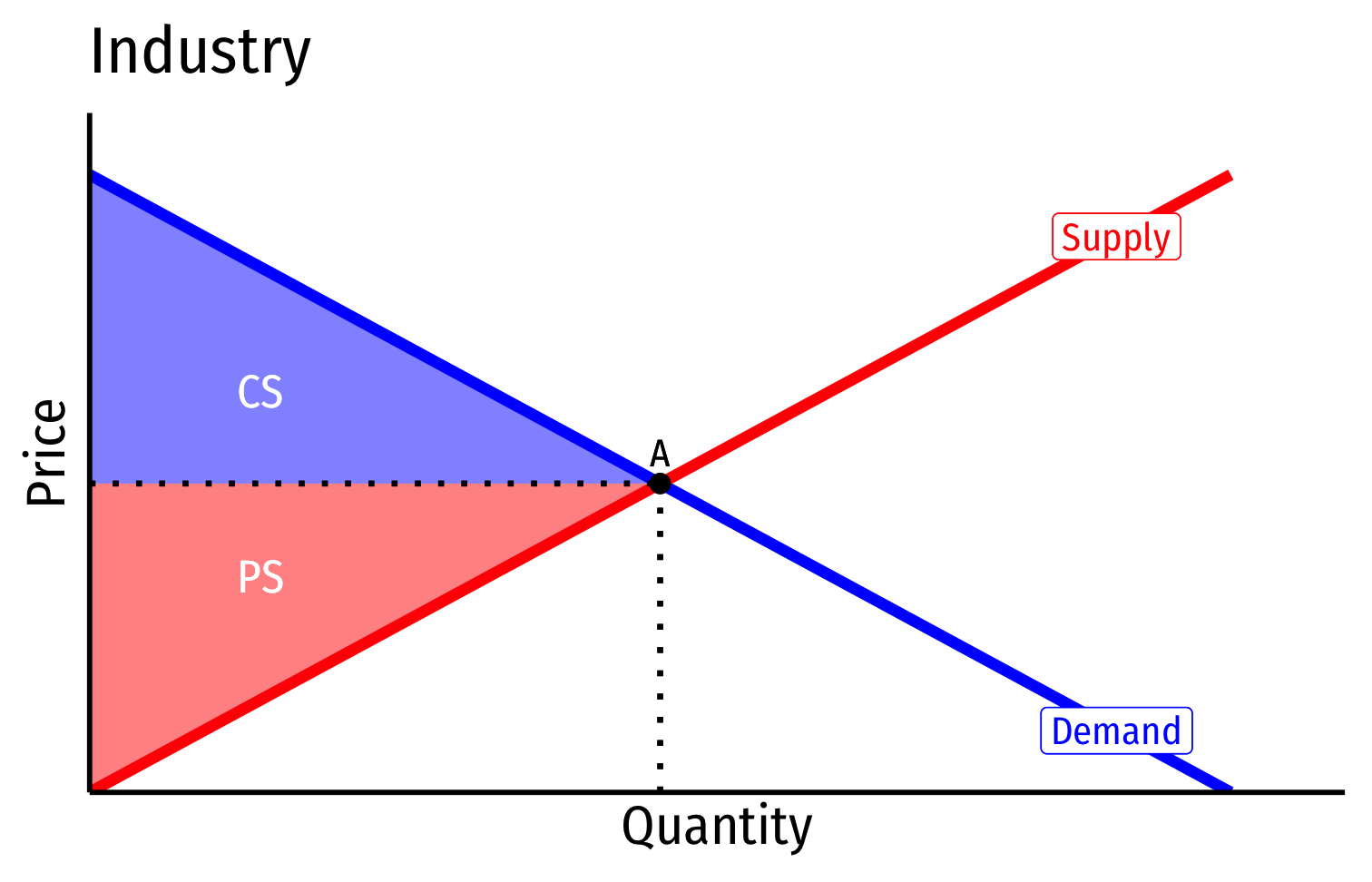

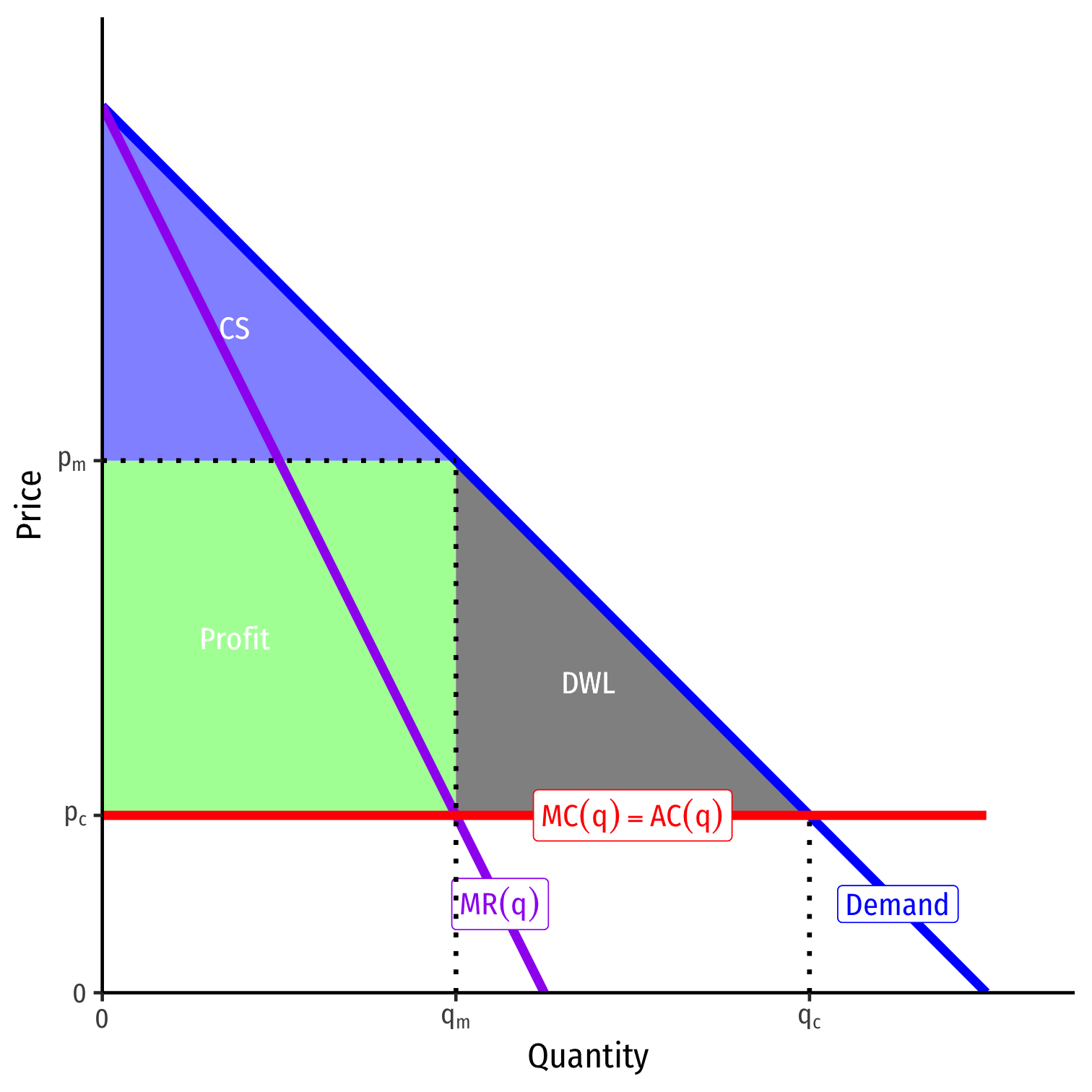

The Social Harm of Market Power

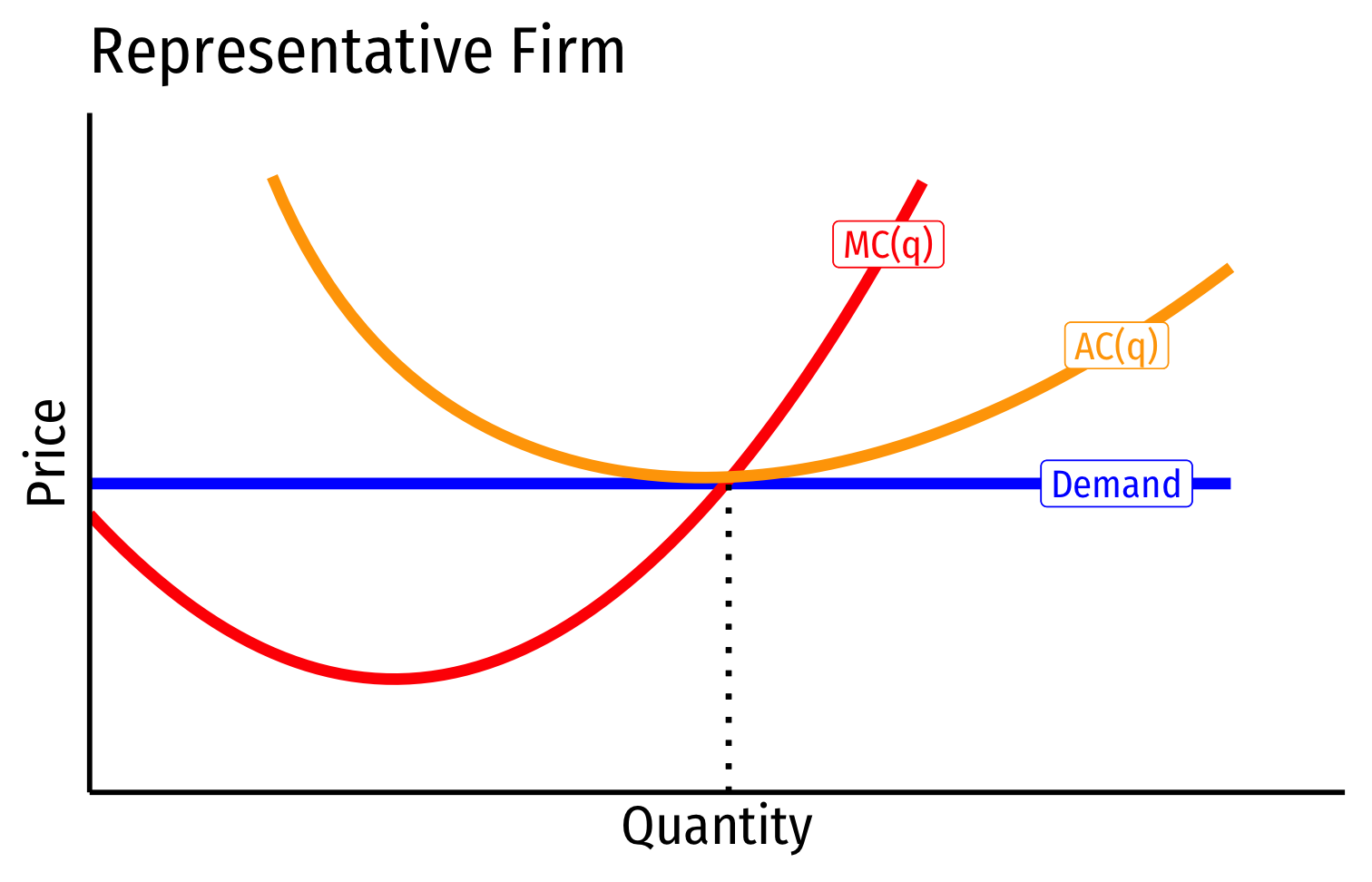

Perfectly Competitive Market

- In a competitive market in long run equilibrium:

- Economic profit is driven to $0; resources (factors of production) optimally allocated

- Allocatively efficient: p=MC(q), maximized CS + PS

- Productively efficient: p=AC(q)min (otherwise firms would enter/exit)

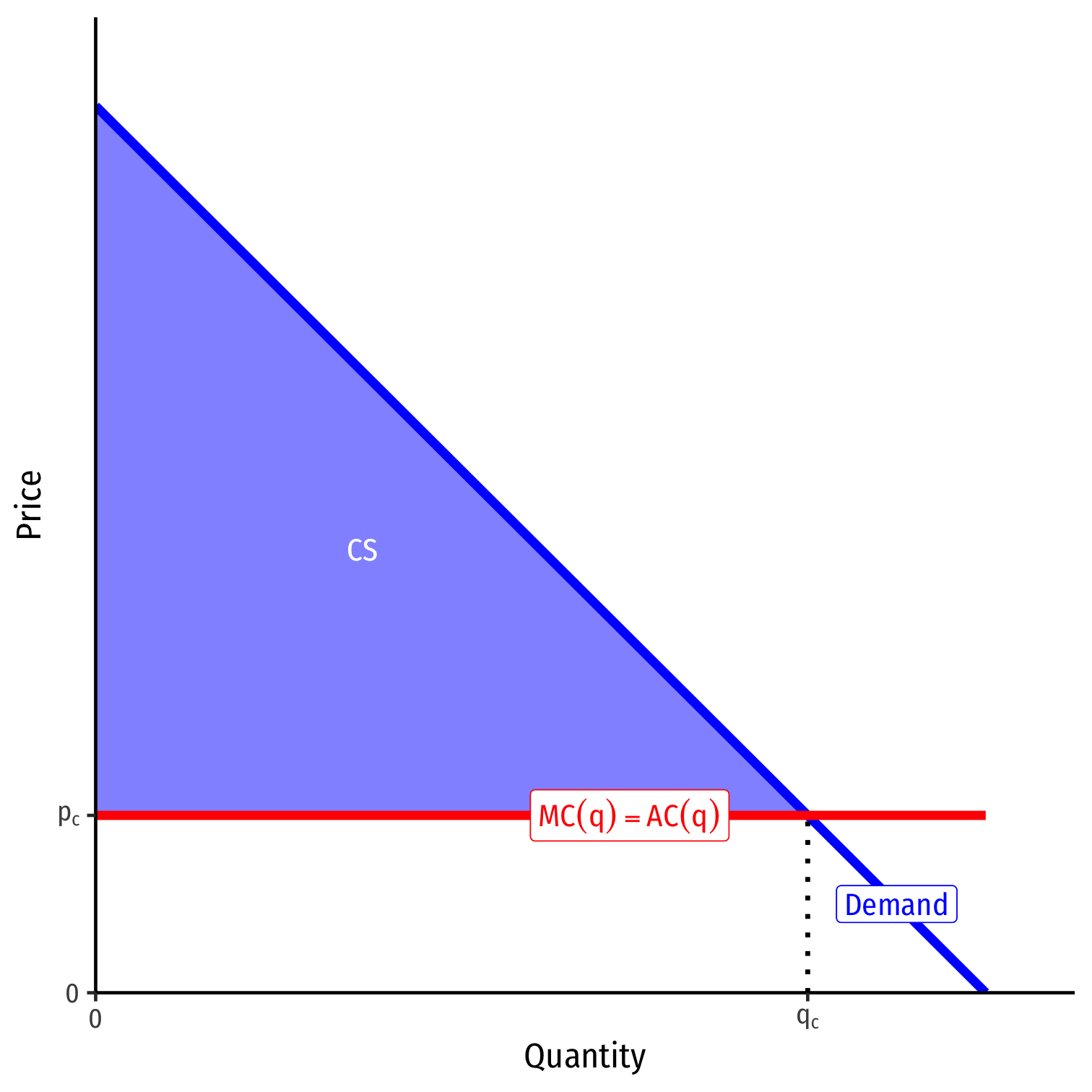

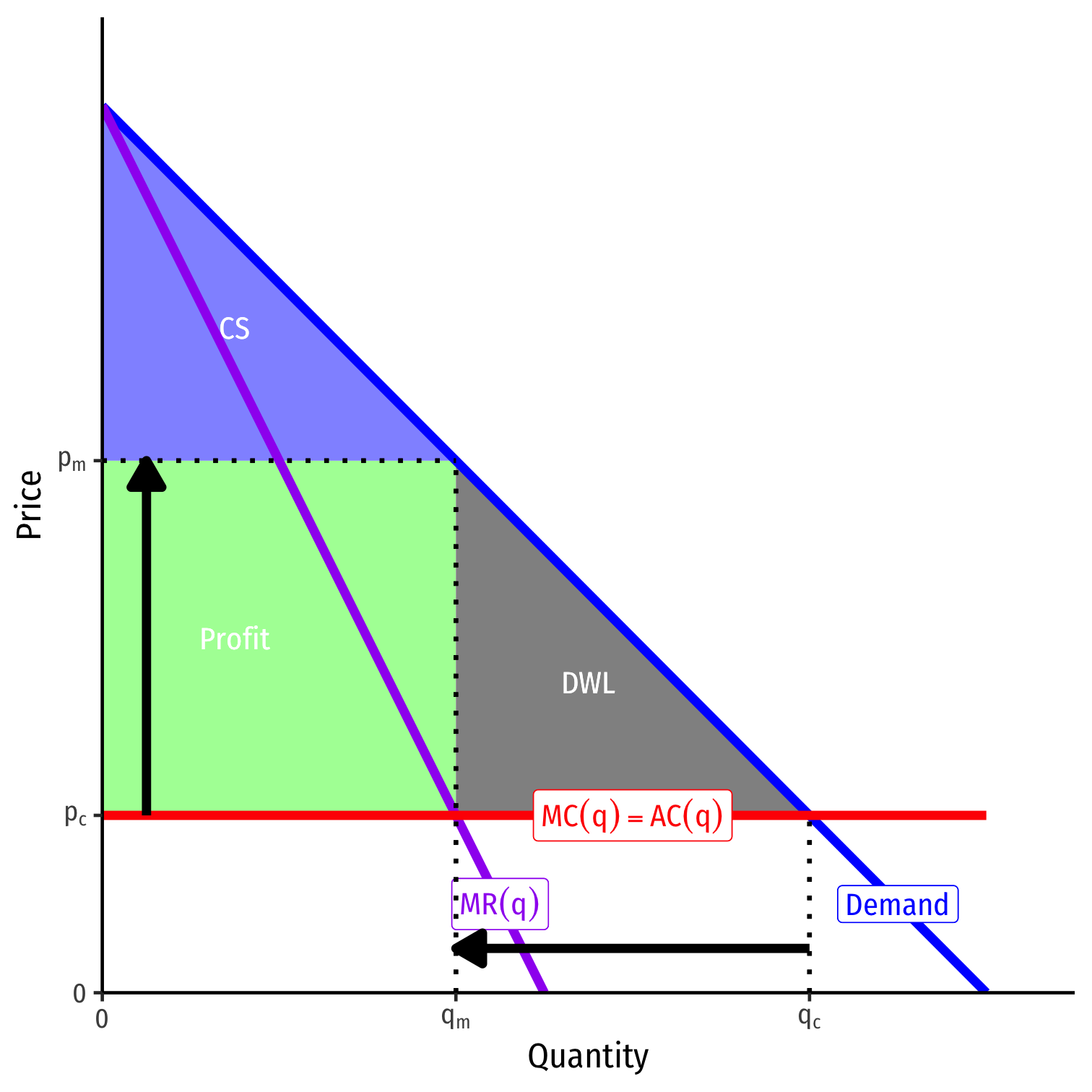

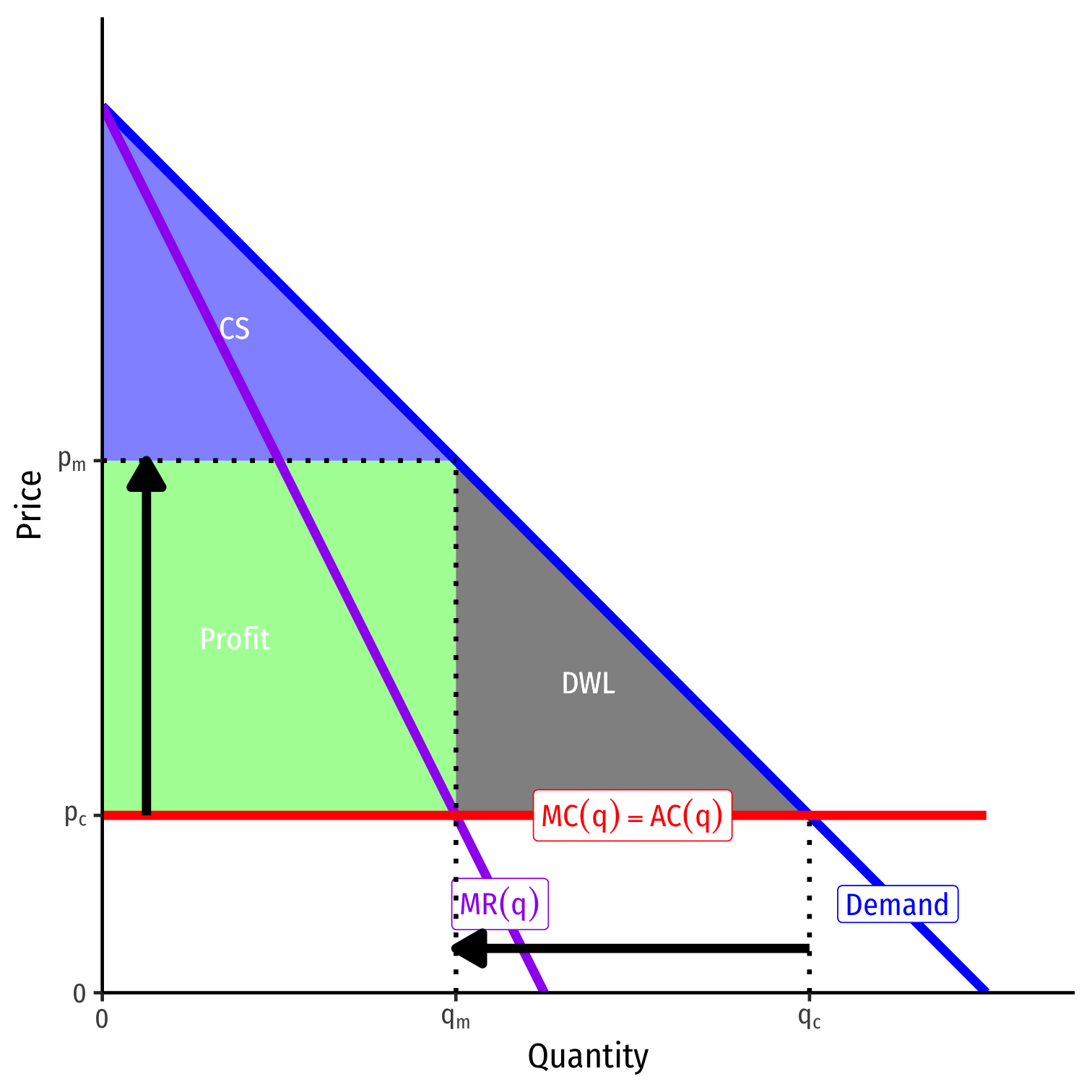

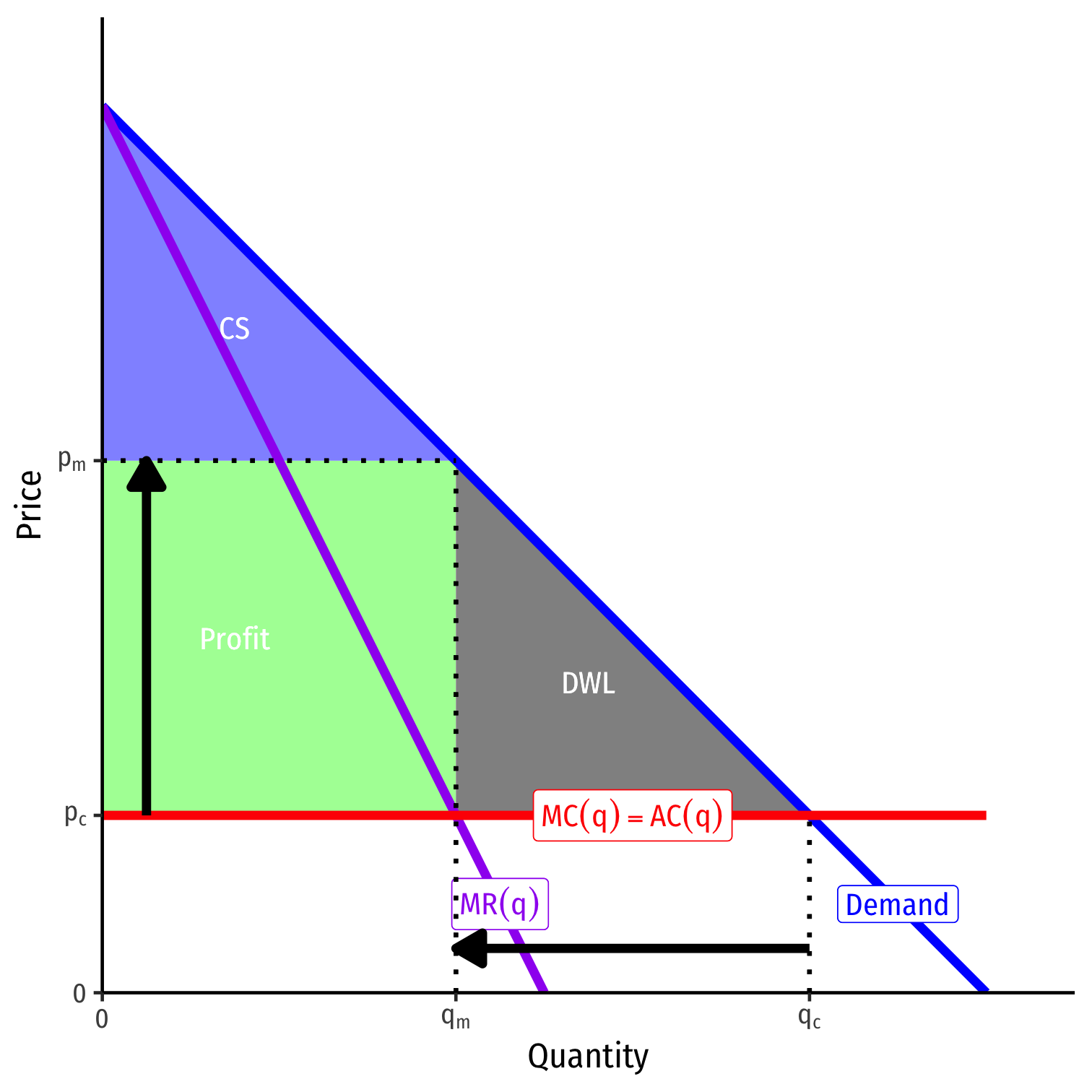

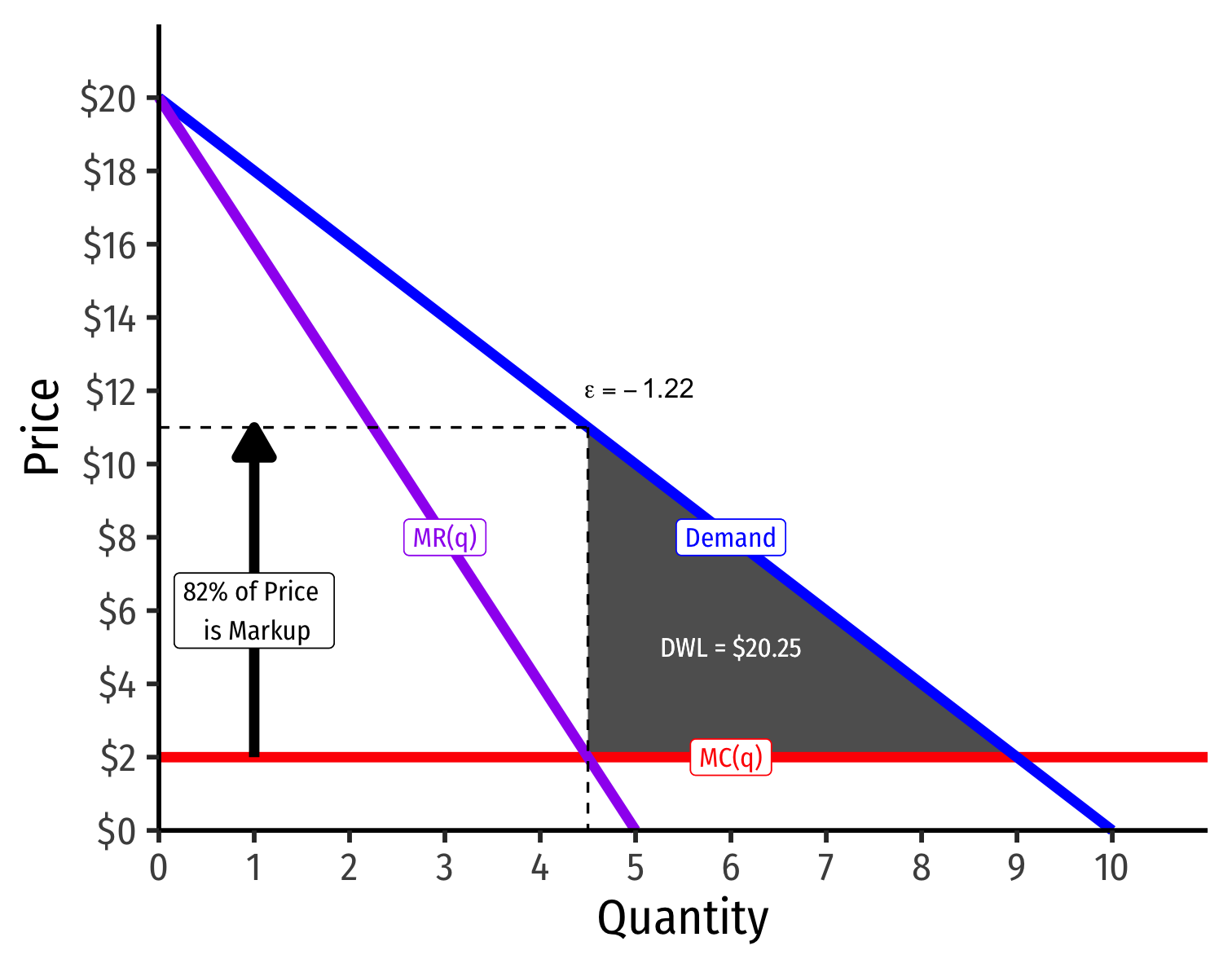

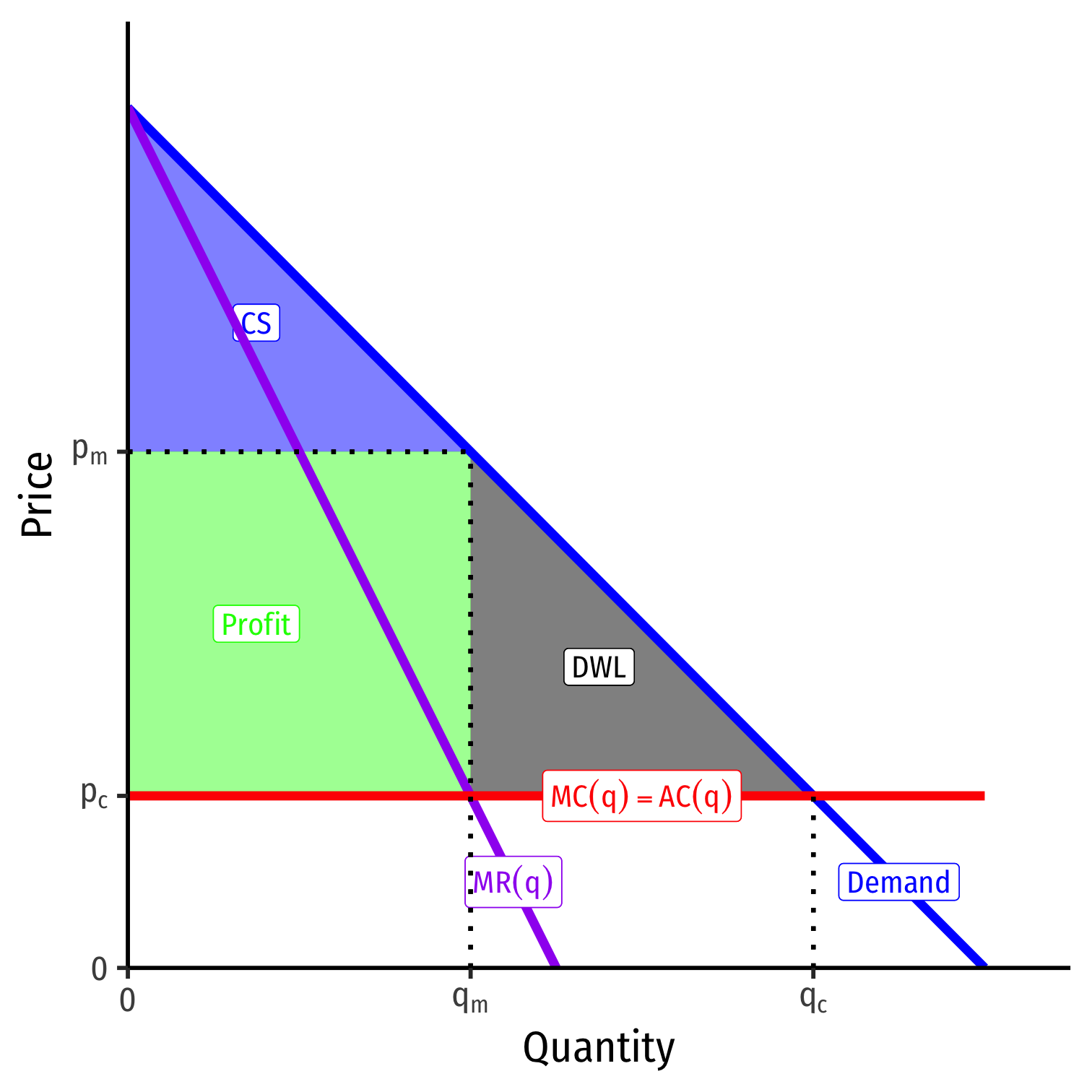

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL I

- Consider an industry with some simplified cost assumptions:

C(q)=cq

- No fixed cost; MC(q)=AC(q)=c†

- If this industry were competitive, firms would set pc=MC(q) and (collectively), industry would produce qc

- Max consumer surplus, π=0

† Why? See here for a reminder.

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL II

A monopolist would face entire industry demand and set (qm,pm):

- Set MR(q) = MC(q): qm

- Raise p to max. WTP (Demand): pm

Restricts output and raises price, compared to competitive market

Earns monopoly profits (p>AC)

Loss of consumer surplus

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL III

- Deadweight loss of surplus destroyed from lost gains from trade

- Consumers willing to buy more than qm, if the monopolist would lower prices!

- Monopolist would benefit by accepting lower prices to sell more than qm, but this would yield less than maximum profits

- main problem is that monopolist must lower price on all units sold

The Bad of Monopoly II

- Deadweight loss of surplus destroyed from lost gains from trade

- Consumers willing to buy more than qm, if the monopolist would lower prices!

- Monopolist would benefit by accepting lower prices to sell more than qm, but this would yield less than maximum profits

- main problem is that monopolist must lower price on all units sold

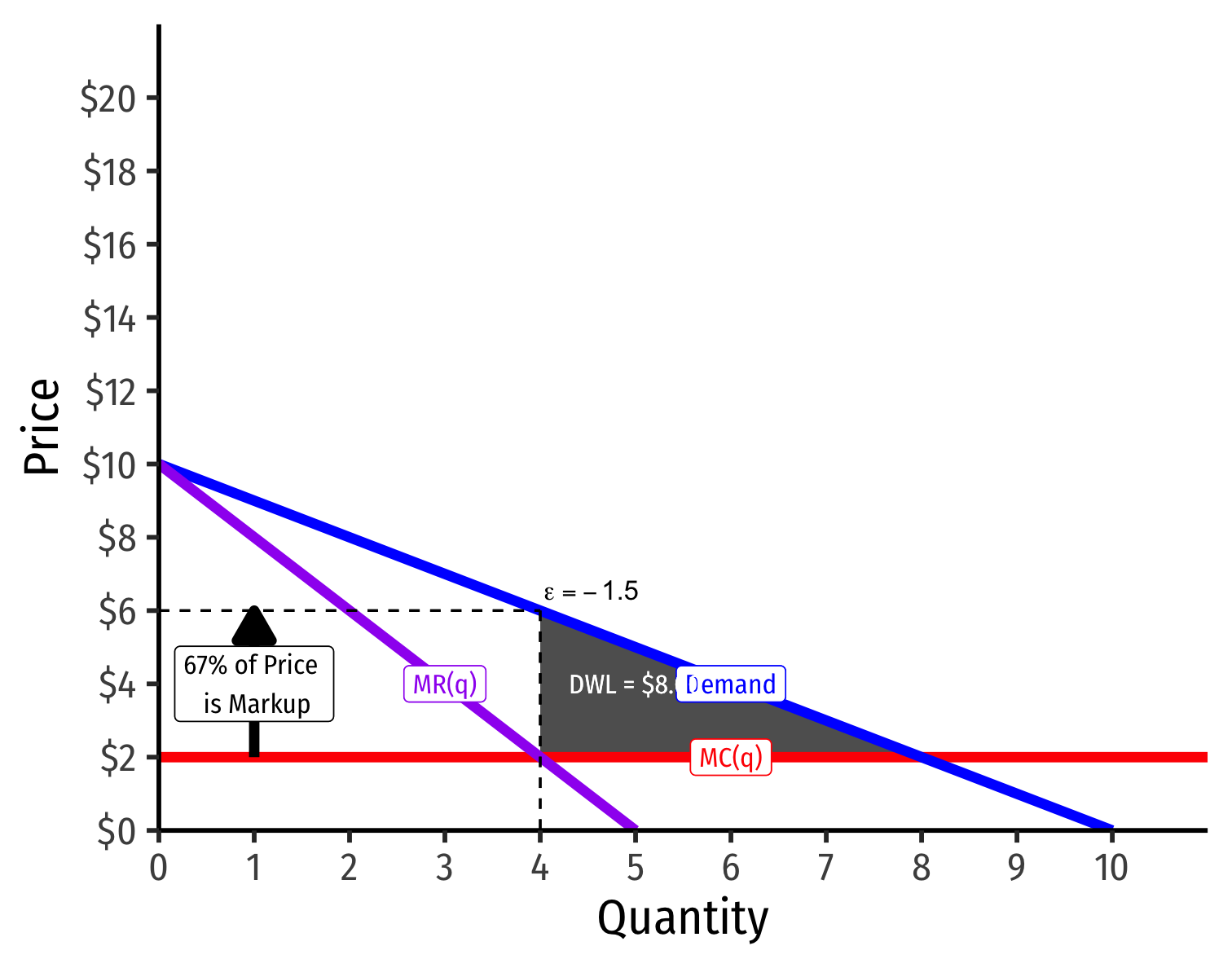

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL III

- Size of DWL depends on:

- price distortion (pm−pc) (varies inversely with demand elasticity)

- quantity distortion (qc−qm) (varies directly with demand elasticity)

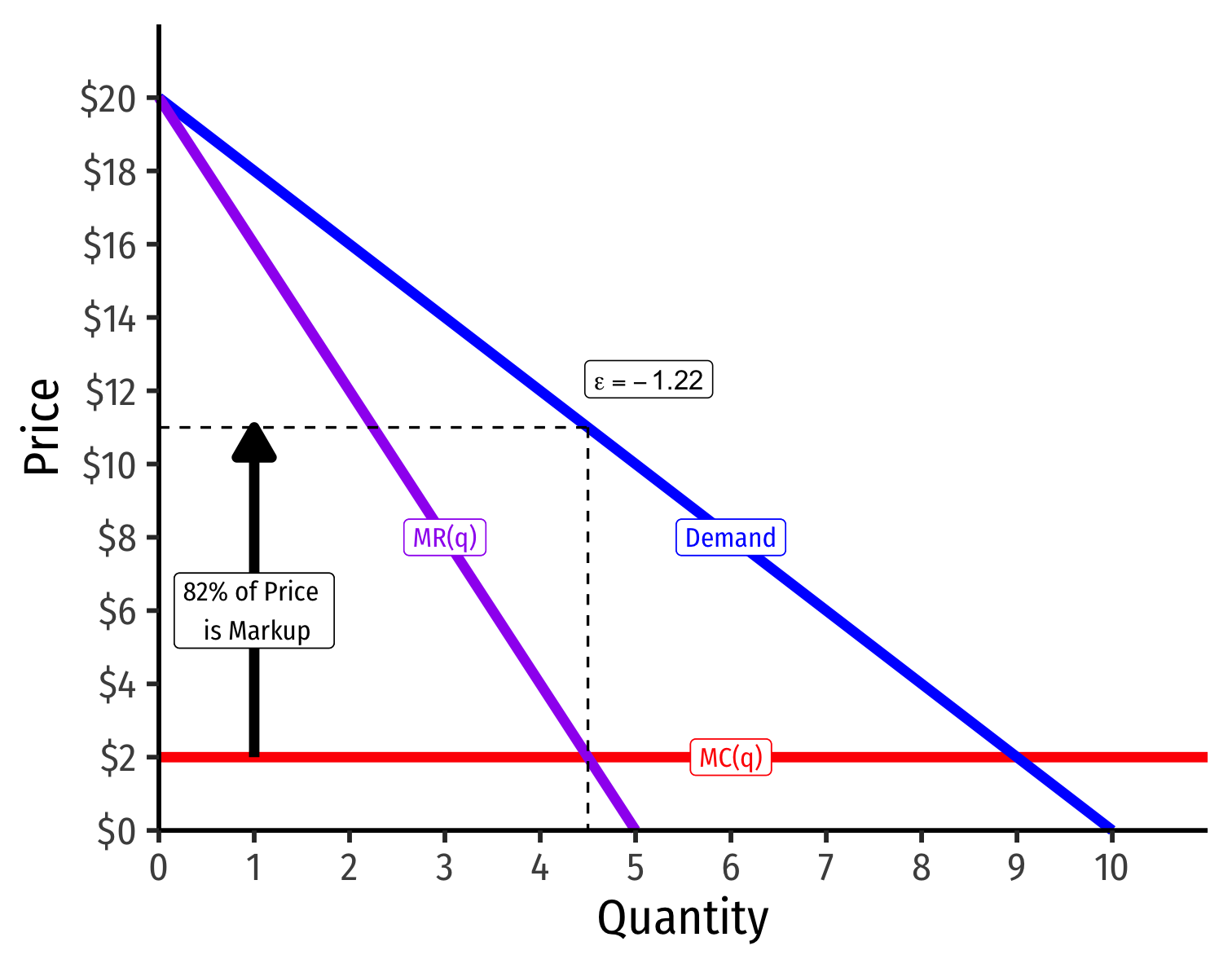

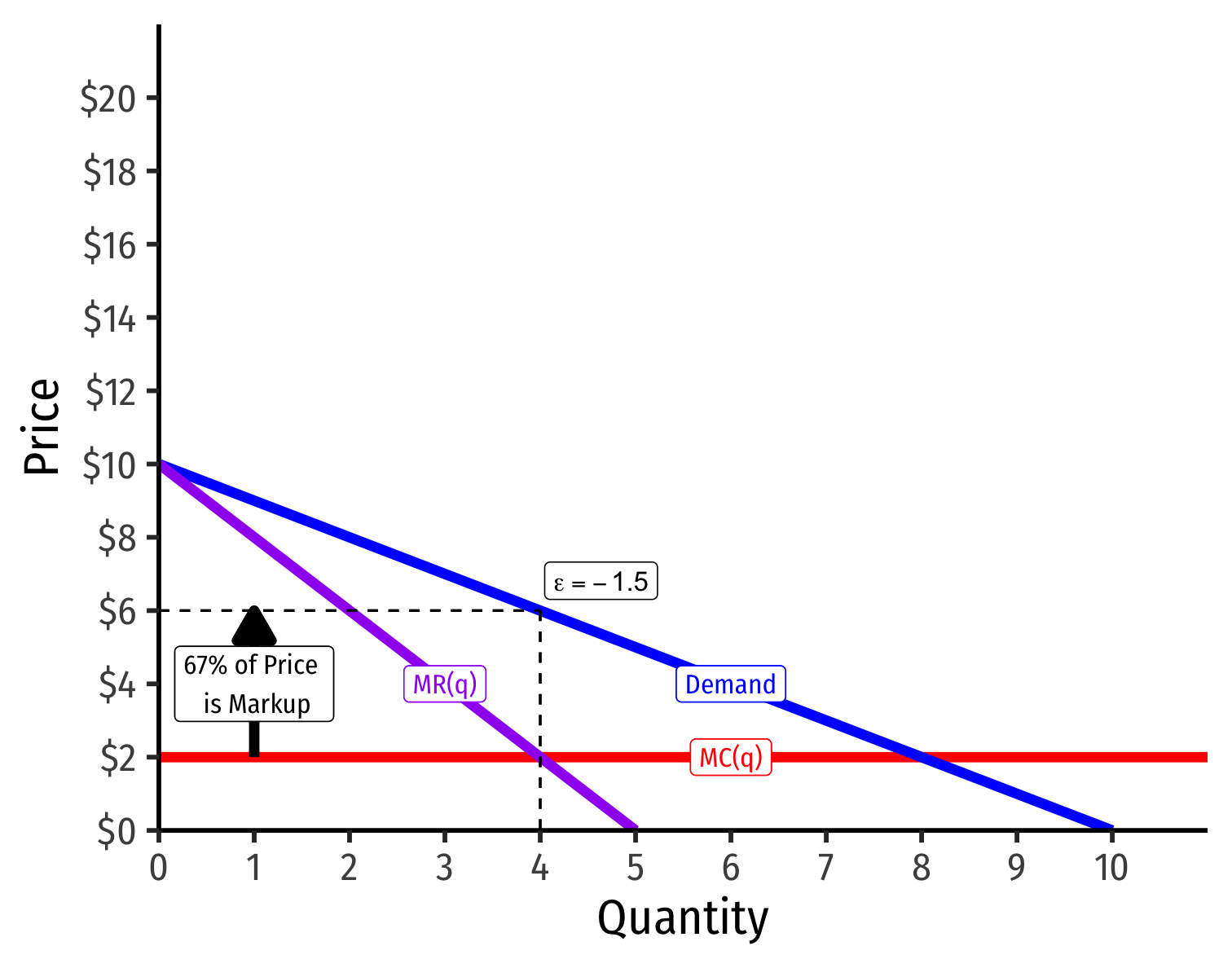

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL IV

Demand Less Elastic at p∗

- Price distortion is larger, quantity distortion smaller

Demand More Elastic at p∗

- Price distortion is smaller, quantity distortion larger

The Bad of Monopoly: DWL V

- In general, with a linear demand curve and constant marginal costs,

DWL=12εPmQmL2

- And more simply:

DWL=π2

DWL VI: Harberger Triangles I

Arnold Harberger 1924 —

“One of the first things we learn when we begin to study price theory is that the main effects of monopoly are to misallocate resources, to reduce aggregate welfare, and to redistribute income in favor of monopolists. In the light of this fact, it is a little curious that our empirical efforts at studying monopoly have so largely concentrated on other things. We have studied particular industries and have come up with a formidable list of monopolistic practices...And we have also studied the whole economy, using the concentration of production in the hands of a small number of firms as the measure of monopoly. On this basis we have obtained the impression that some 20 or 30 or 40 per cent of our economy is effectively monopolized,” (77).

“In this paper I propose to look at the American economy, and in particular at American manufacturing industry, and try to get some quantitative notion of the allocative and welfare effects of monopoly. It should be clear from the outset that this is not the kind of job one can do with great precision. The best we can hope for is to get a feeling for the general orders of magnitude that are involved,” (77).

Harberger, Arnold C, 1954, “Monopoly and Resource Allocation,” American Economic Review 44(2): 77-87

DWL VI: Harberger Triangles II

Arnold Harberger 1924 —

“Thus we come to our final conclusion. Elimination of resource misallocations in American manufacturing in the late twenties would bring with it an improvement in consumer welfare of just a little more than a tenth of a per cent. In present values, this welfare gain would amount to about $2.00 per capita,” (84).

“I must confess that I was amazed at this result. I never really tried to quantify my notions of what monopoly misallocations amounted to, and I doubt that many other people have. Still, it seems to me that our literature of the last twenty or so years reflects a general belief that monopoly distortions to our resources structure are much greater than they seem in fact to be,” (86).

Harberger, Arnold C, 1954, “Monopoly and Resource Allocation,” American Economic Review 44(2): 77-87

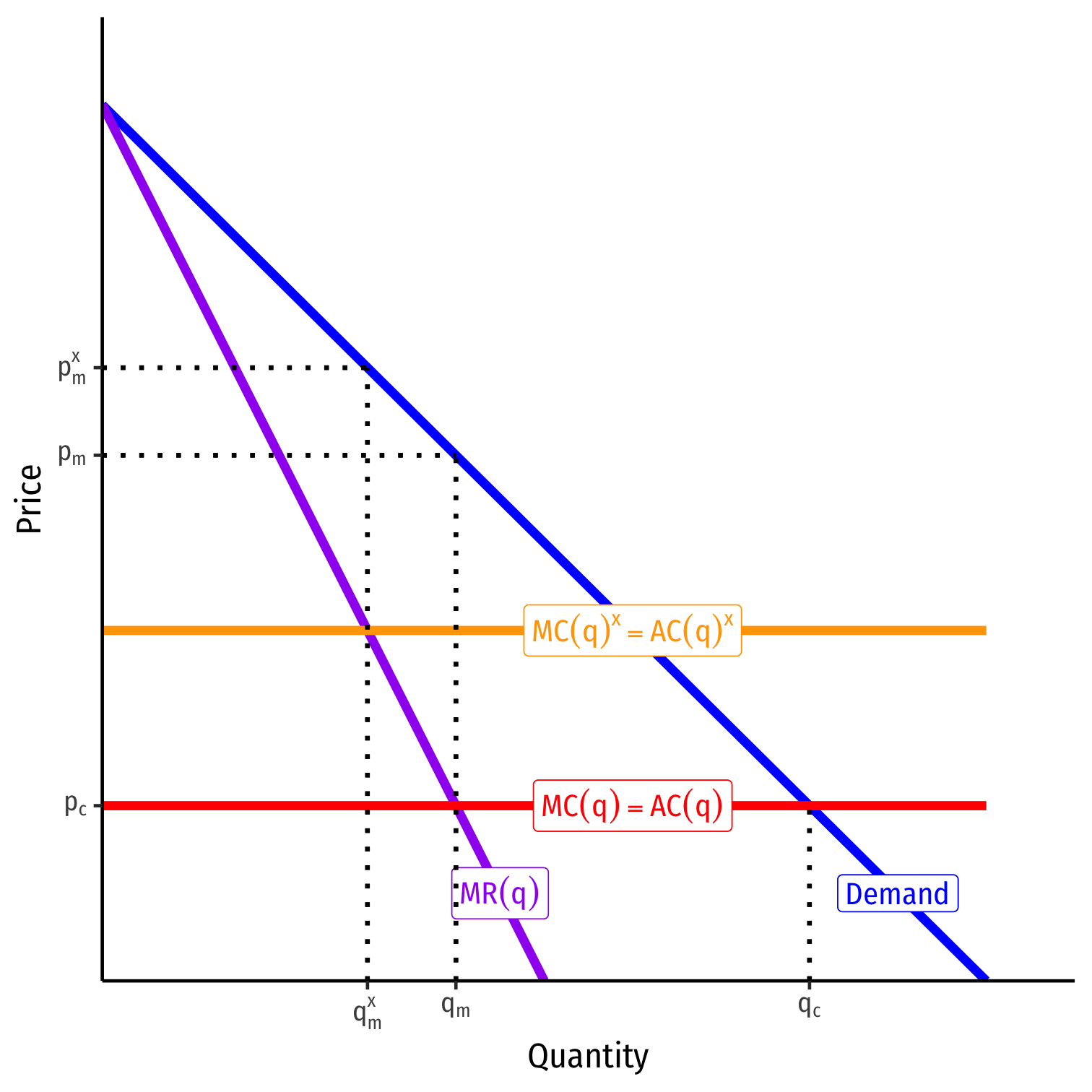

The Bad of Monopoly: X-Inefficiency

“The best of all monopoly profits is a quiet life” - Sir John Hicks

Monopoly may generate “X-inefficiency”

Lack of competition causes monopoly to be complacent or lazy

- May inefficiently raise costs of production

Creates further distortions (lost surpluses)

In General

What Is a Monopoly?

What Is a Monopoly?

Everyone (economists & the public alike) generally agree that monopoly is bad

But what is a monopoly?

A surprisingly difficult question to answer!

In Ye Olde Days

Lord Edward Coke

1552—1634

Chief Justice (King's Bench)

“A monopoly is an institution or allowance by the king, by his grant, commission, or otherwise...to any person or persons, bodies politic or corporate, for the sole buying, selling, making, working, or using of anything, whereby any person or persons, bodies politic or corporate, are sought to be restrained of any freedom or liberty that they had before, or hindered in their lawful trade,” (181).

Coke, Edward, 1648, Institutes of the laws of England, Part 3

In Ye Olde Days

"[A man lives] in a house built with monopoly bricks, with windows...of monopoly glass; heated by monopoly coal (in Ireland monopoly timber), burning in a grate made of monopoly iron...He washed himself in monopoly soap, his clothes in monopoly starch. He dressed in monopoly lace, monopoly linen, monopoly leather, monopoly gold thread...His clothes were dyed with monopoly dyes. He ate monopoly butter, monopoly currants, monopoly red herrings, monopoly salmon, and monopoly lobsters. His food was seasoned with monopoly salt, monopoly pepper, monopoly vinegar...He wrote with monopoly pens, on monopoly writing paper; read (through monopoly spectacles, by the light of monopoly candles) monopoly printed books," (quoted in Acemoglu and Robinson 2011, pp.187-188).

Hill, Christopher, (1961), The Century of Revolution

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson, 2013, Why Nations Fail

Isn’t a Single Seller a Monopolist?

- Isn’t the only seller of something a monopolist?

- A new inventor?

- An artist?

- LeBron James?

- First-mover?

- The only hardware store in town?

- The only seafood restaurant?

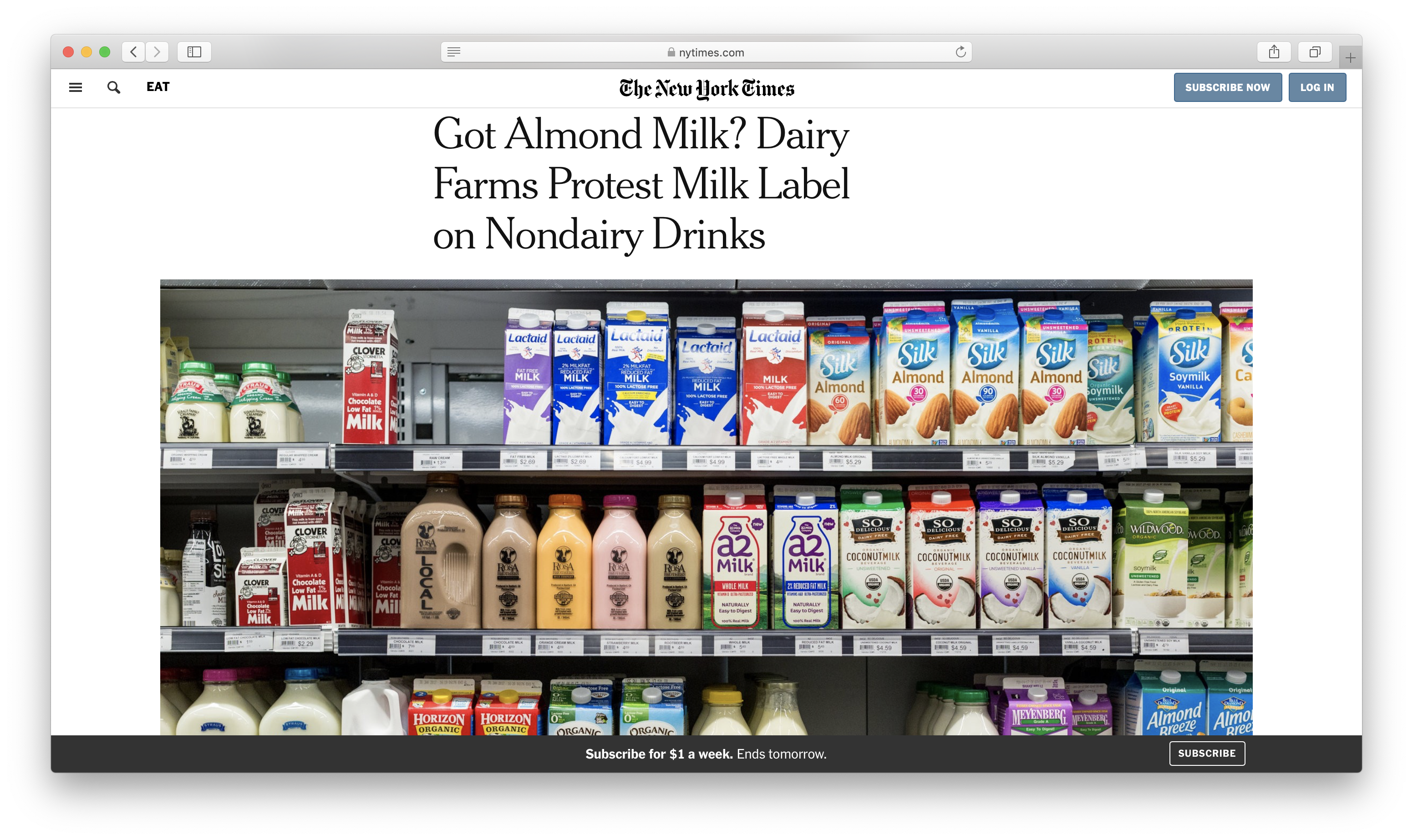

Maybe...Depends on the Elasticity!

The more (less) price elastically a good, the less (more) market power: L=p−MC(q)p=−1ϵ

Demand Less Elastic at p∗

Demand More Elastic at p∗

Maybe...Depends on the Elasticity!

Market power: ability to profitably raise p>MC

Depends on ability of consumers to find substitutes when firm raises its price

- Supply side substitution: consumers switch to other producers of the same product

- Demand side substitution: consumers switch to consuming other acceptable products

More (fewer) substitutes ⟹ higher price elasticity of demand ⟹ more market power

Maybe...Depends on the Elasticity!

- (Own) Price elasticity of demand: measure of responsiveness

εqx,px=%Δqx%Δpx

- Cross-price elasticity of demand: measure of responsiveness

εqx,py=%Δqx%Δpy

Elasticities Matter!

“For every product substitutes exist. But a relevant market cannot meaningfully encompass that infinite a range. The circle must be drawn narrowly to exclude any other product to which, within reasonable variations in price, only a limited number of buyers will turn; in technical terms, products whose 'cross-elasticities of demand' are small,” Times-Picayune Publishing v. United States, 345 U.S. 594 at 621 n. 31 (1953)

“Every manufacturer is the sole producer of the particular commodity it makes but its control in the above sense of the relevant market depends on the availability of alternative commodities for buyers: i.e., whether there is a cross-elasticity of demand between cellophane and the other wrappings,” U.S. v. E. I. du Pont de Nemours &. Co., 351 U.S. 377 (1956)

“Cross-price elasticity is a more useful tool than own-price elasticity in defining a relevant antitrust market. Cross-price elasticity estimates tell one where the lost sales will go when the price is raised, while own-price elasticity estimates simply tell one that a price increase would cause a decline in volume,” New York v. Kraft General Foods, 926 F. Supp. 321 (1995)

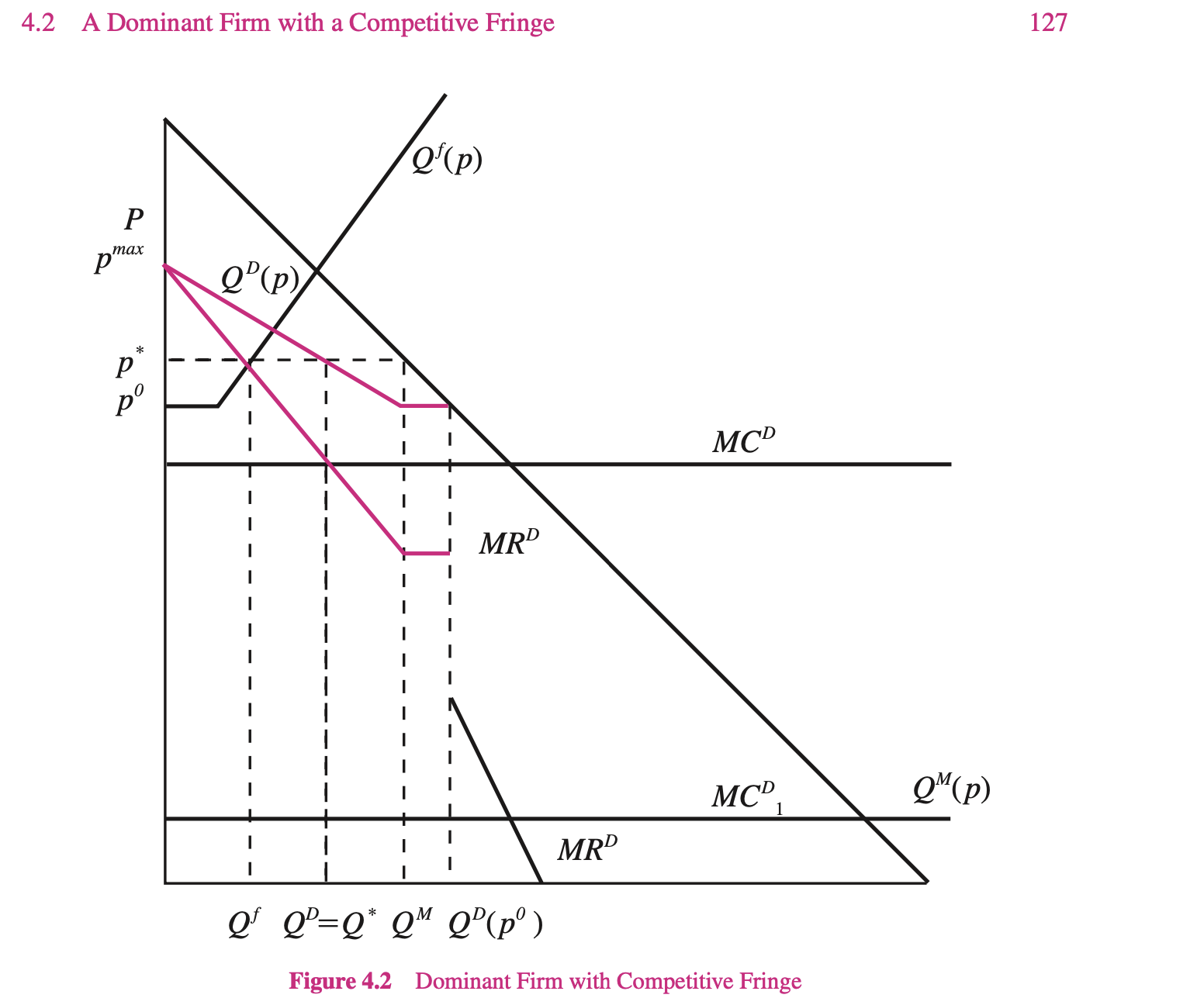

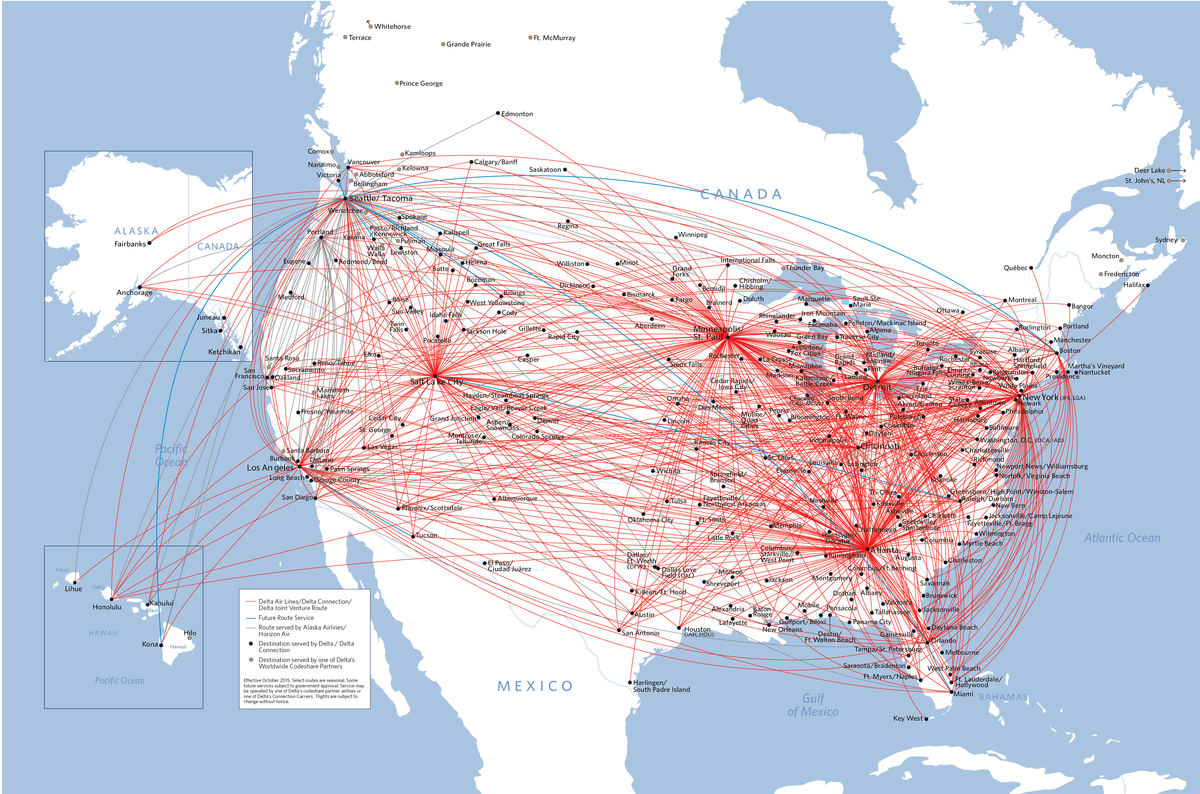

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe I

Monopoly (a single firm) is easy to work with in theory, harder to find in practice

More common to have “near monopolies” with a dominant firm that has large (but not 100%) market share

- Often more efficient than rivals (e.g. economies of scale)

- Or has a superior product

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe II

- Other firms (“competitive fringe”), let’s assume (for now) have no market power and are price-takers — they supply output at price chosen by dominant firm

- Set pD=MCf

- Total fringe supply: n∑f=1MCf

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe III

- Supply from fringe at price chosen by dominant firm (pD) dampens (but doesn't eliminate) the (residual) demand for dominant firm as it raises price

- Makes its demand more elastic (ready supply-side substitutes)

- Reduces its market power

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe IV

Church and Ware, 2000, p. 127

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe V

LD=p−MCDp=sDεfssf+ε

- LD: dominant firm’s market power (Lerner index)

- sD: dominant firm’s market share

- εfs: competitive fringe’s price elasticity of supply

- sf: competitive fringe’s market share

- ε: price elasticity of market demand

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe VI

LD=p−MCDp=sDεfssf+ε

- Market power of dominant firm (LD) is affected by three things:

- ε Elasticity of market demand

- more elastic demand reduces market power of dominant firm

- εfs Elasticity of fringe supply

- greater supply response to dominant firm raising price

- depends on fringe’s MCf

- More efficient dominant firm is compared to fringe (MCD<MCf)

- ε Elasticity of market demand

Dominant Firms with a Competitive Fringe VII

LD=p−MCDp=sDεfssf+ε

An endogenous relationship between market power (LD) & market share (sD)!

- Larger (sD) implies larger LD

With no competitive fringe, sf=0, sD=1, εfs=0, we are left with LD=p−MCDp=1ε

- Simple monopoly solution

- Presence of fringe essentially increases elasticity ε

Entry Barriers

Market Power Persists Because of Entry Barriers

Monopoly exists, and persists, because of barriers to entry

- otherwise, profits would get competed away by new entrants

- markets become competitive over time as entrepreneurs enter & produce substitutes

How easy is it to enter and compete with incumbent firm?

Market Power Persists Because of Entry Barriers

Remember the long run equilibrium condition in competitive markets: no profitable entry

- Potential entrants must expect negative profits after entering

Key corporate strategy: entry deterrence

- Silicon Valley talks about “moats”

Public policy concerns: entry barriers impede competition and thus efficiency; (but may be benefits in some cases)

Market Power Persists Because of Entry Barriers

(Some) possible types of entry barriers:

- Control over key resource: Ricardian rents

- Structural/technological: Name/brand recognition, high fixed/sunk costs, economies of scale, network externalities

- Government regulation: Intellectual property rights, occupational licensing, public franchises, burdensome compliance, rent-seeking

- Strategic behavior by incuments: aggressive postentry behavior, predatory pricing, raising rivals’ costs, lowering rivals’ revenues

“Natural” vs. “artificial” barriers to entry

- “open” vs. “closed” monopoly

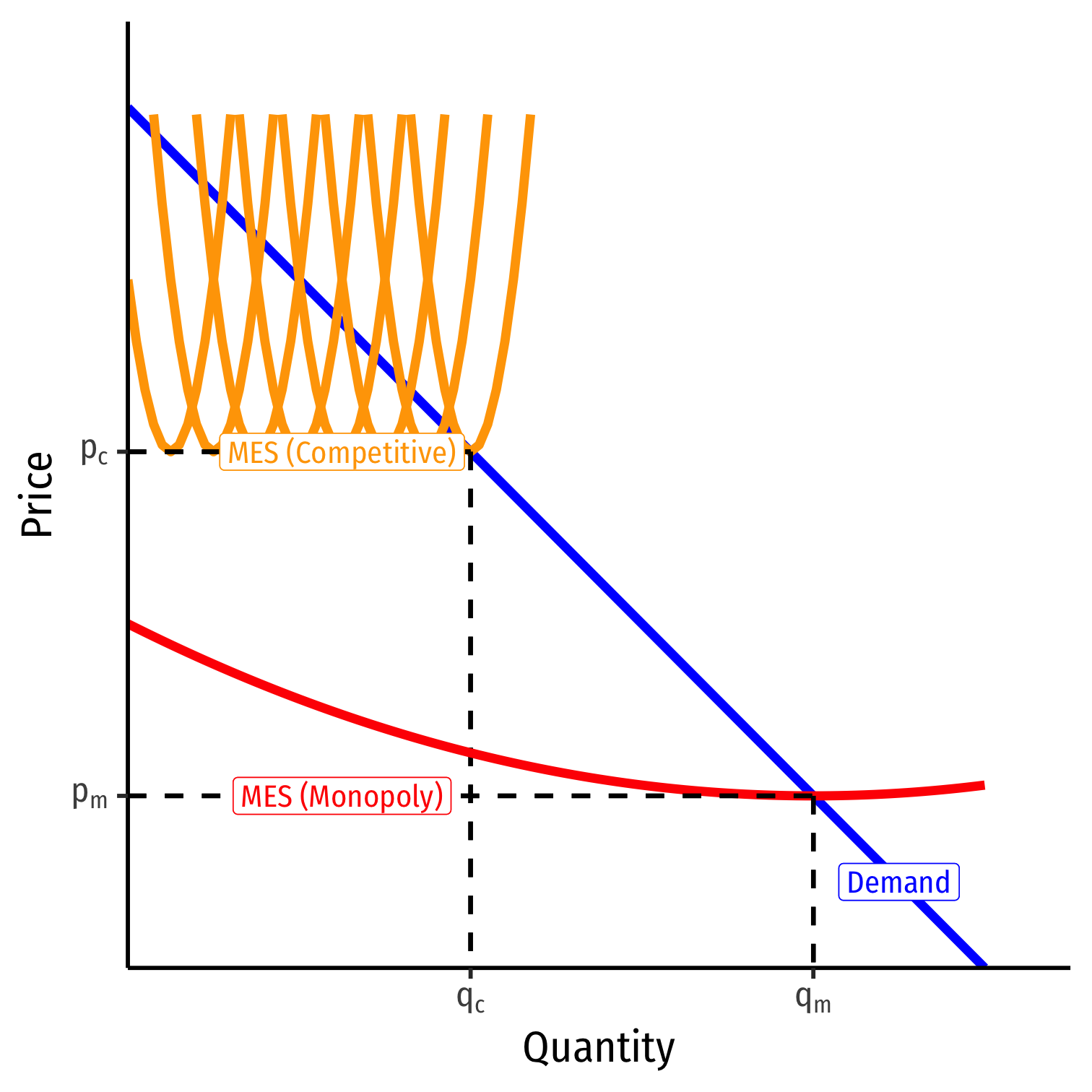

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly

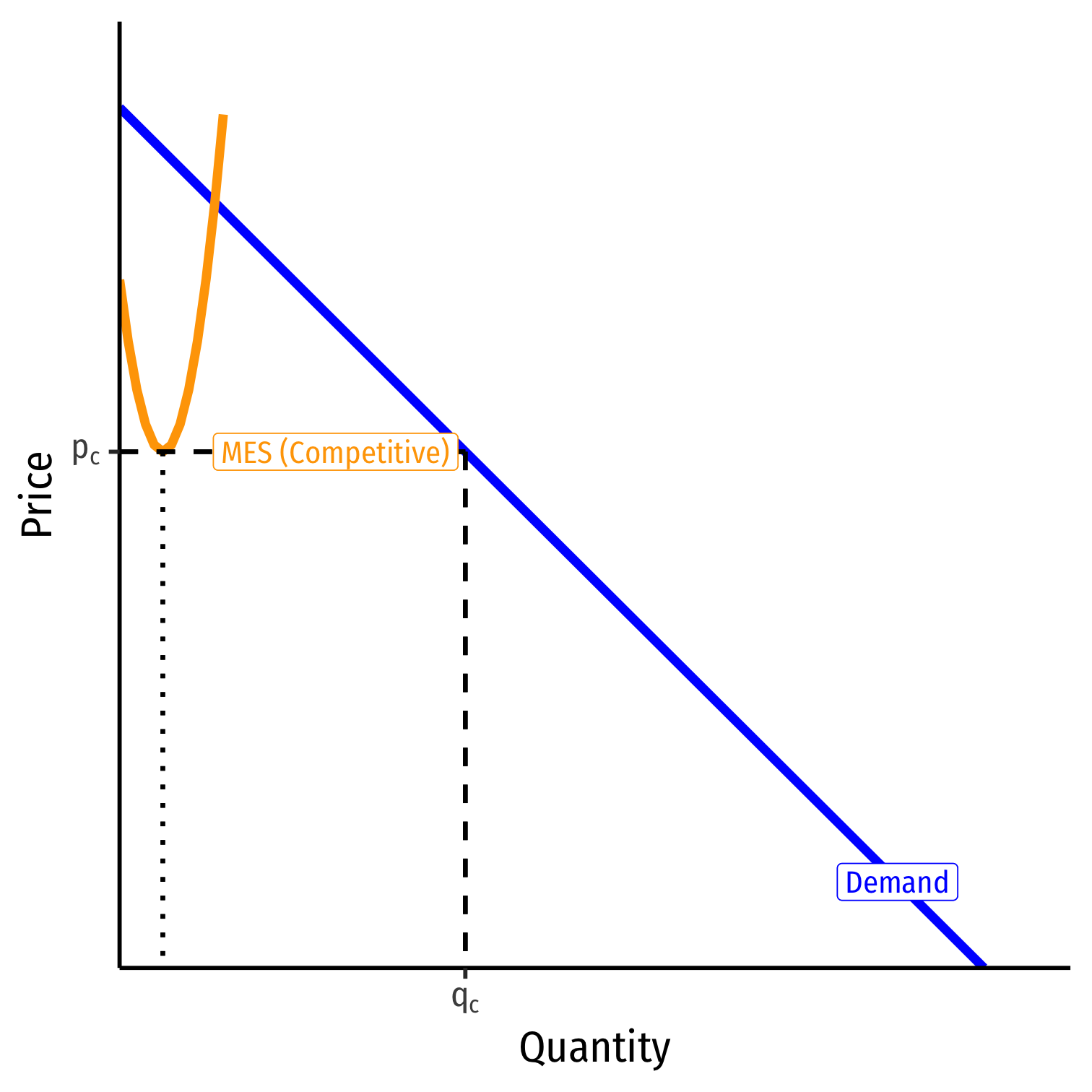

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

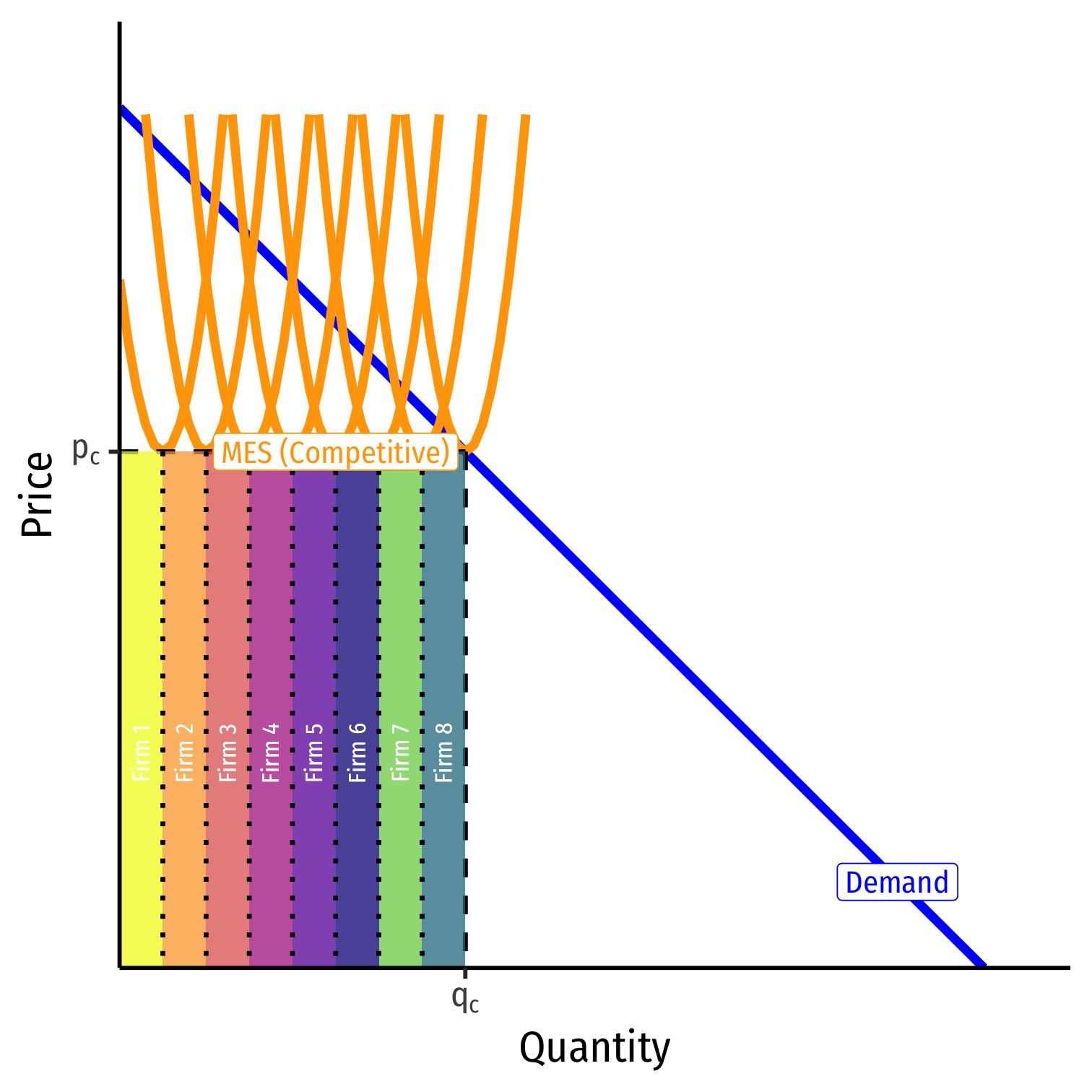

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

- ...can fit more identical firms into the industry!

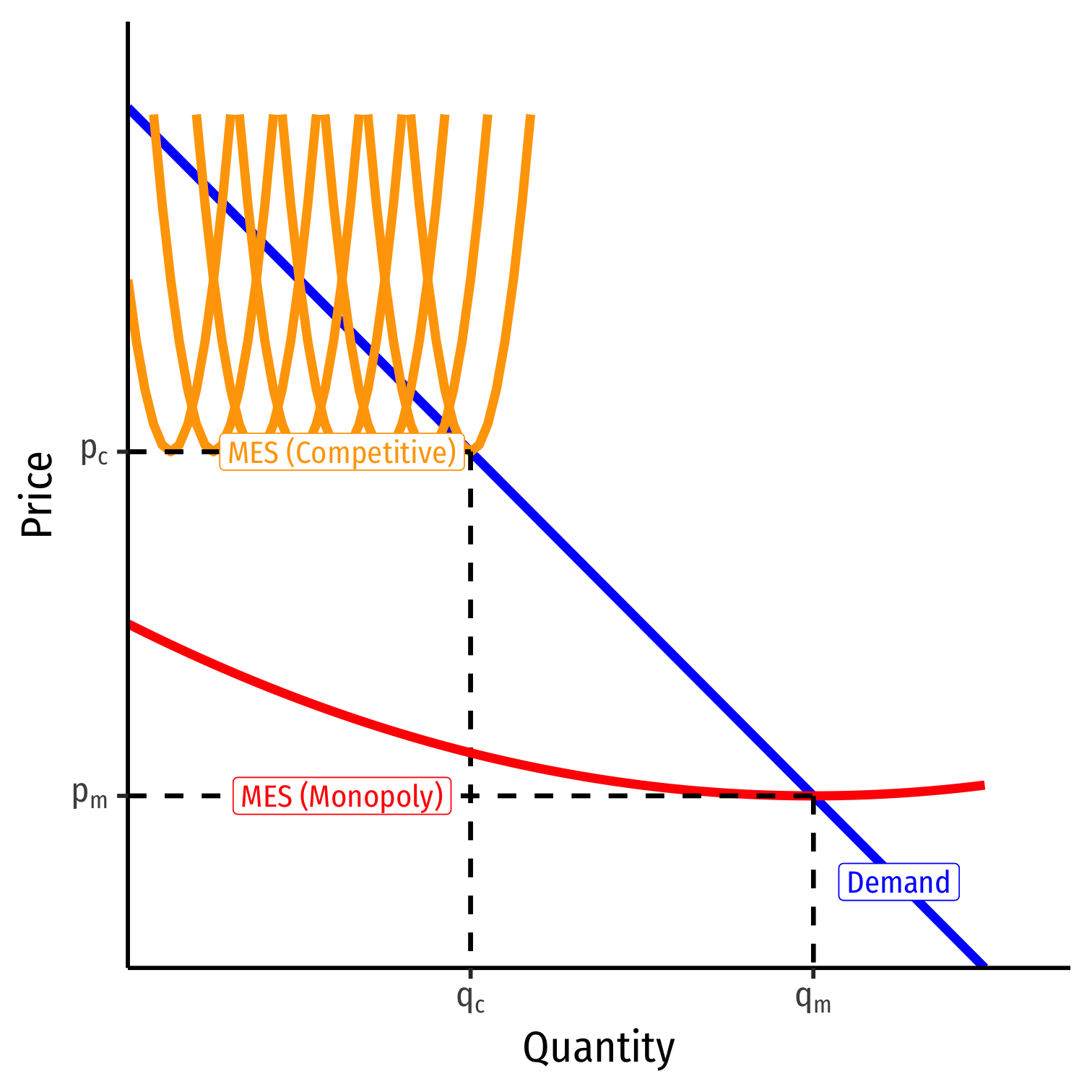

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

- If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

A natural monopoly that can produce higher q∗ and lower p∗ than a competitive industry!

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly II

Example: Imagine a single isolated condo complex with 1,000 units far from any other buildings or telco infrastructure

- Fixed costs: laying fiber optics to the complex is $100,000

- Marginal costs: connecting each unit: $0

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly II

- Suppose 10 providers split the complex, each laying down their own cables, and each serving 100 units:

AC(100)=$100,000100=$1,000/subscriber

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly II

- Suppose 1 provider serves the complex serving all 1,000 units:

AC(1,000)=$100,0001000=$100/subscriber

Government Entry Regulation

Intellectual Property I

For alleged economic reasons, patent (for ideas and inventions) and copyright (for expressions) laws exist

- owners can sue competitors for infringement

Grant temporary monopoly to recover fixed costs & provide incentive to undertake (risky and expensive) research/creativity

- similar to natural monopoly!

A tradeoff between incentives & access

See my intellectual property lecture from Economics of the Law for more

Entry Regulation

The United States Postal Service is the only provider of first class mail allowed by order of the government

Starting another business that delivers mail is illegal

“Whoever establishes any private express for the conveyance of letters or packets, or in any manner causes or provides for the conveyance of the same by regular trips or at stated periods over any post route which is or may be established by law...shall be fined...or imprisoned...or both.” (18 U.S.C. § 1696)

Entry Regulation

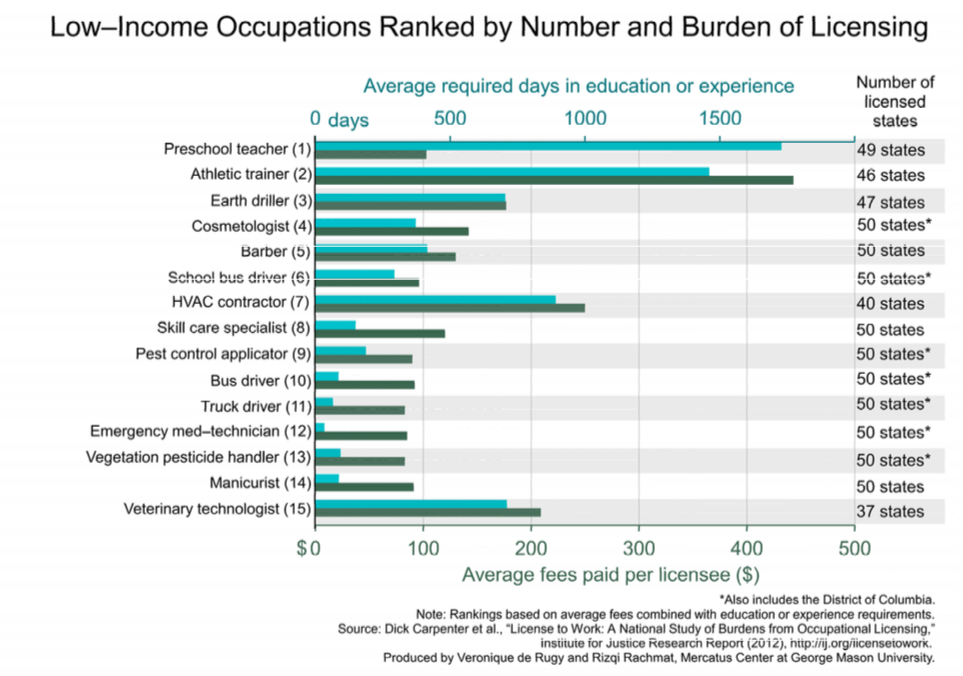

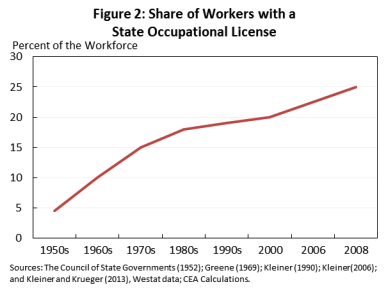

Entry Regulation: Occupational Licensing I

In 1950, 1 in 20 jobs required a license. Today it's 1 in 4. Source: Obama White House (2015): Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers

Occupational Licensing II

Revenue Source for Government I

Many governments create entry restrictions to create monopoly rents in order to extract some from the monopolist as revenue source

Historically, a primary source of state revenue (inability to tax)

- Medieval guilds

- “Letters patent”

Revenue Source for Government II

Revenue Source for Government II

The Ugly of Market Power: Rent-Seeking

The Ugly of Market Power: Rent-Seeking I

The monopoly profits earned with market power are an economic rent

- A windfall return above opportunity cost (MC)

- Creates an artificial scarcity from restricting entry & competition

This is the “prize” of market power

The Ugly of Market Power: Rent-Seeking II

Think of an economic rent as a “prize,” the payment a person receives for a good above its opportunity cost

Creating rents creates competition for the rents, causing people to invest resources in rent-seeking

The social cost of the rent is all of the resources invested in rent-seeking!

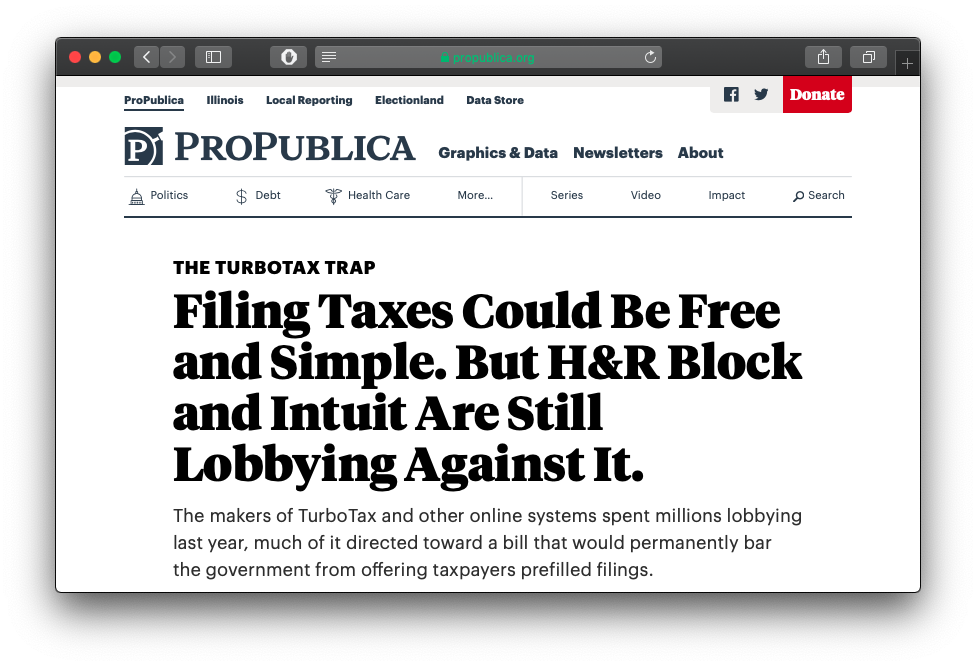

Government Intervention Creates Rents I

Political authorities intervene in markets in various ways that benefit some groups at the expense of everyone else

- subsidies to groups (often producers)

- regulation of industries

- tariffs, quotas, and special exemptions from these

- tax breaks and loopholes

- conferring monopoly and other privileges

See Mitchell (2013) in today’s readings for examples

Government Intervention Creates Rents I

These interventions create economic rents for their beneficiaries by restricting competition

This is a transfer of wealth from consumers/taxpayers to politically-favored groups

The problem in politics is you cannot give away money for free even if you tried!

The promise of earning a rent breeds competition over the rents (rent-seeking)

- investments of resources to lobby political officials

Rent-Seeking

Gordon Tullock

1922-2014

“The rectangle to the left of the [Deadweight loss] triangle is the income transfer that a successful monopolist can extort from the customers. Surely we should expect that with a prize of this size dangling before our eyes, potential monopolists would be willing to invest large resources in the activity of monopolizing. ... Entrepreneurs should be willing to invest resources in attempts to form a monopoly until the marginal cost equals the properly discounted return,” (p.231).

Tullock, Gordon, (1967), "The Welfare Cost of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft," Western Economic Journal 5(3): 224-232.

If You Look at the World Long Enough...

If You Look at the World Long Enough...

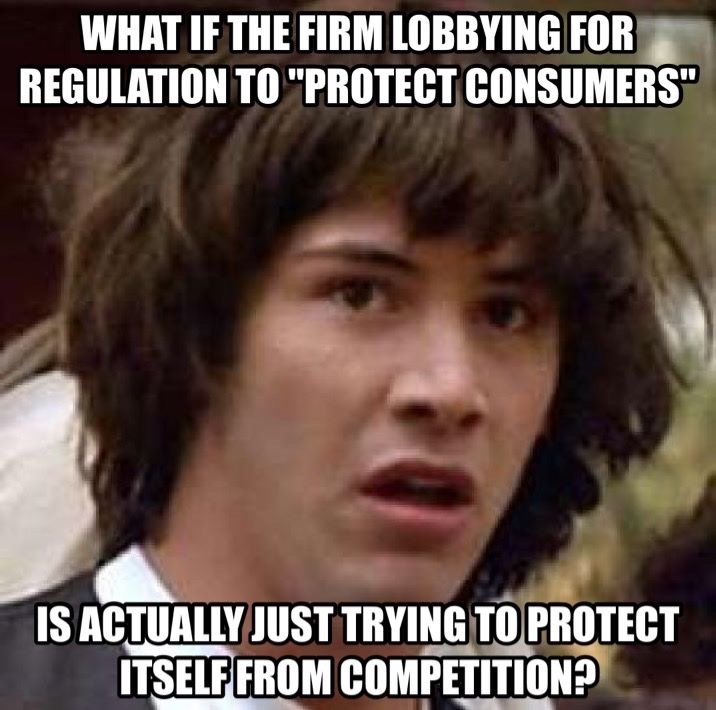

Regulation has a Dark Side

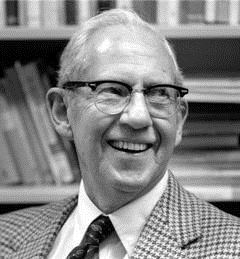

George Stigler

1911-1991

Economics Nobel 1982

“[A]s a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefits,” (p.3).

“[E]very industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to control entry. In addition, the regulatory policy will often be so fashioned as to retard the rate of growth of new firms,” (p.5).

Stigler, George J, (1971), “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3:3-21

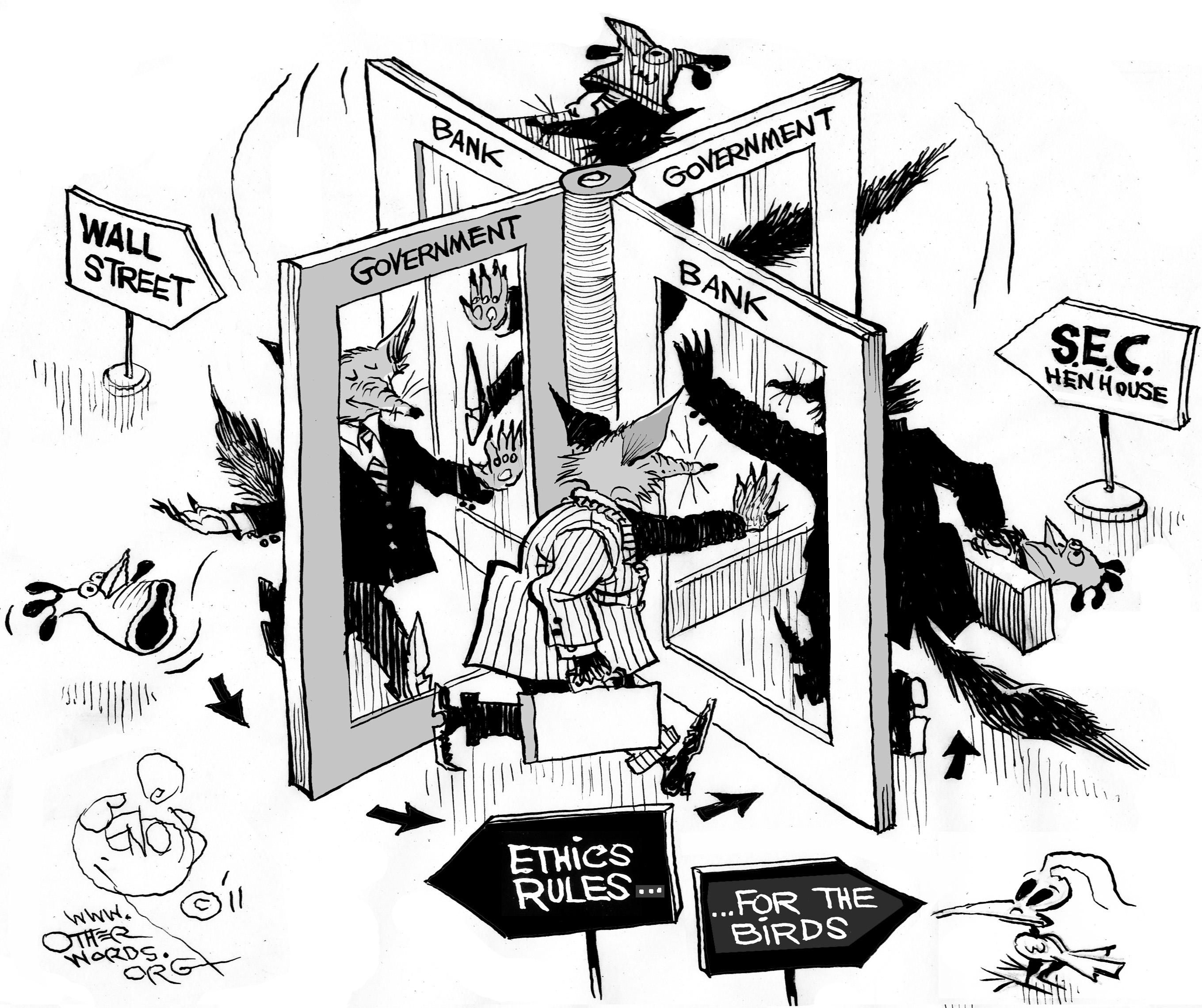

Regulation has a Dark Side

Regulatory capture: a regulatory body is “captured” by the very industry it is tasked with regulating

Industry members use agency to further their own interests

- Incentives for firms to design regulations to harm competitors

- Legislation & regulations written by lobbyists & industry-insiders

Regulation has a Dark Side

One major source of capture is the “revolving door” between the public and private sector

Legislators & regulators retire from politics to become highly paid consultants and lobbyists for the industry they had previously “regulated”