2.2 — Cournot Competition

ECON 326 • Industrial Organization • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/ioS23

ioS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Models of Oligopoly

Three canonical models of Oligopoly

- Bertrand competition

- Firms simultaneously compete on price

- Cournot competition

- Firms simultaneously compete on quantity

- Stackelberg competition

- Firms sequentially compete on quantity

Cournot Competition on Moblab

Cournot Competition on Moblab

- Each of you is a firm selling identical scooters

- Each season, each firm chooses its quantity to produce

- You pay a cost for each you produce (identical across all firms)

- Market price depends on total industry output

- More total output ⟹⟹ lower market price

- Market price is revealed after all firms have chosen their output

Cournot Competition on Moblab

- We will play 4 times:

- You are the only firm (monopoly)

- You will be matched with another firm (duopoly)

- You will be matched with 2 other firms (triopoly)

- The entire class is competing in the same market

- Each instance will have 3 rounds

Cournot's Model

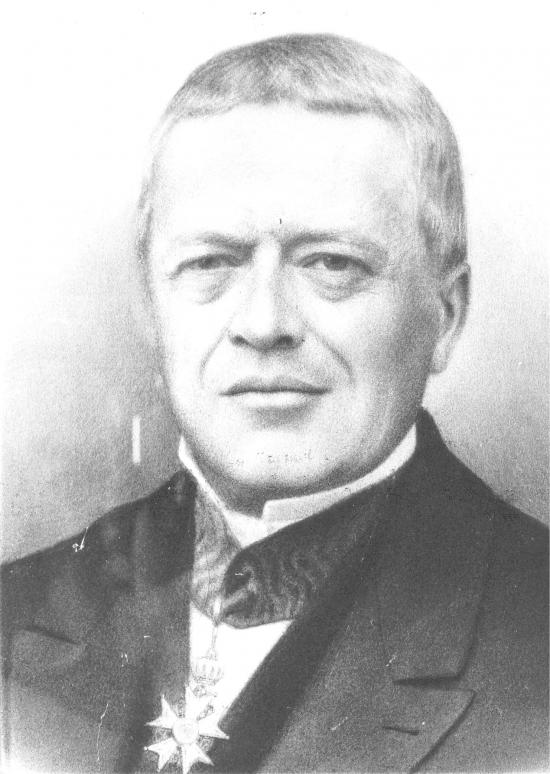

Cournot

Antoine Augustin Cournot

1801-1877

1838 Researches on the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth

First writer to:

- ✅ use and advocate mathematics for study of political economy

- ✅ relate demand and supply as functions of price and quantity

- ✅ draw a demand and supply graph

- ✅ use marginal analysis to find profit-maximizing output: where marginal revenue == marginal cost

Sadly, no influence in his lifetime, but enormous consequence on neoclassical economics

Cournot, Antoine Augustin, 1838, Researches on the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth

Cournot's Model

Antoine Augustin Cournot

1801-1877

- Chapter V “Of Monopoly”, studies a monopoly supplier of mineral water who prices to maximize profit

- MR=MCMR=MC

Cournot's Model

Antoine Augustin Cournot

1801-1877

“Let us now imagine two proprietors and two springs of which qualities are identical and which on account of their similar positions supply the same market in competition.”

“In this case the price is necessarily the same for each proprietor.”

“If pp is the price, D=F(p)D=F(p) the total sales, D1D1 the sales from the spring (1), and D2D2 the sales from the spring (2), then D1+D2=DD1+D2=D.”

- Chapter VII “Of Competition of Producers”

Cournot's Model

Antoine Augustin Cournot

1801-1877

“If, to begin with, we neglect the cost of production, the respective incomes of the proprietors will be pD1pD1 and pD2pD2 and...each of them independently will seek to make this income as large as possible.”

“[But] [p]roprietor (1) can have no direct influence on the determination of D2D2.”

“All that he can do when D2D2 has been determined by proprietor (2) is to choose for D1D1 the value which is best for him. This he will be able to accomplish by properly adjusting his price...except as proprietor (2), who seeing himself forced to accept his price and this value of D2D2, may adopt a new value for D2D2 more favorable ot his interests than the preceding one.”

- Chapter VII “Of Competition of Producers”

Cournot Competition

Antoine Augustin Cournot

1801-1877

We use modern game theory and Nash equilibrium to make Cournot’s model a static game (for now)

“Cournot competition”: two (or more) firms compete on quantity to sell the same good

Firms set their quantities simultaneously

Firms' joint output determines the market price faced by all firms

Cournot Competition: Mechanics

Suppose two firms (1 and 2), each have an identical constant cost MC(q)=AC(q)=cMC(q)=AC(q)=c

Firm 1 and Firm 2 simultaneously set quantities, q1q1 and q2q2

Total market demand is given by

P=a−bQQ=q1+q2P=a−bQQ=q1+q2

Cournot Competition: Mechanics

- Firm 1's profit is given by:

π1=q1(P−c)π1=q1(a−b(q1+q2)−c)π1=q1(P−c)π1=q1(a−b(q1+q2)−c)

And, symmetrically same for firm 2

Note each firm's profits depend (in part) on the output of the other firm!

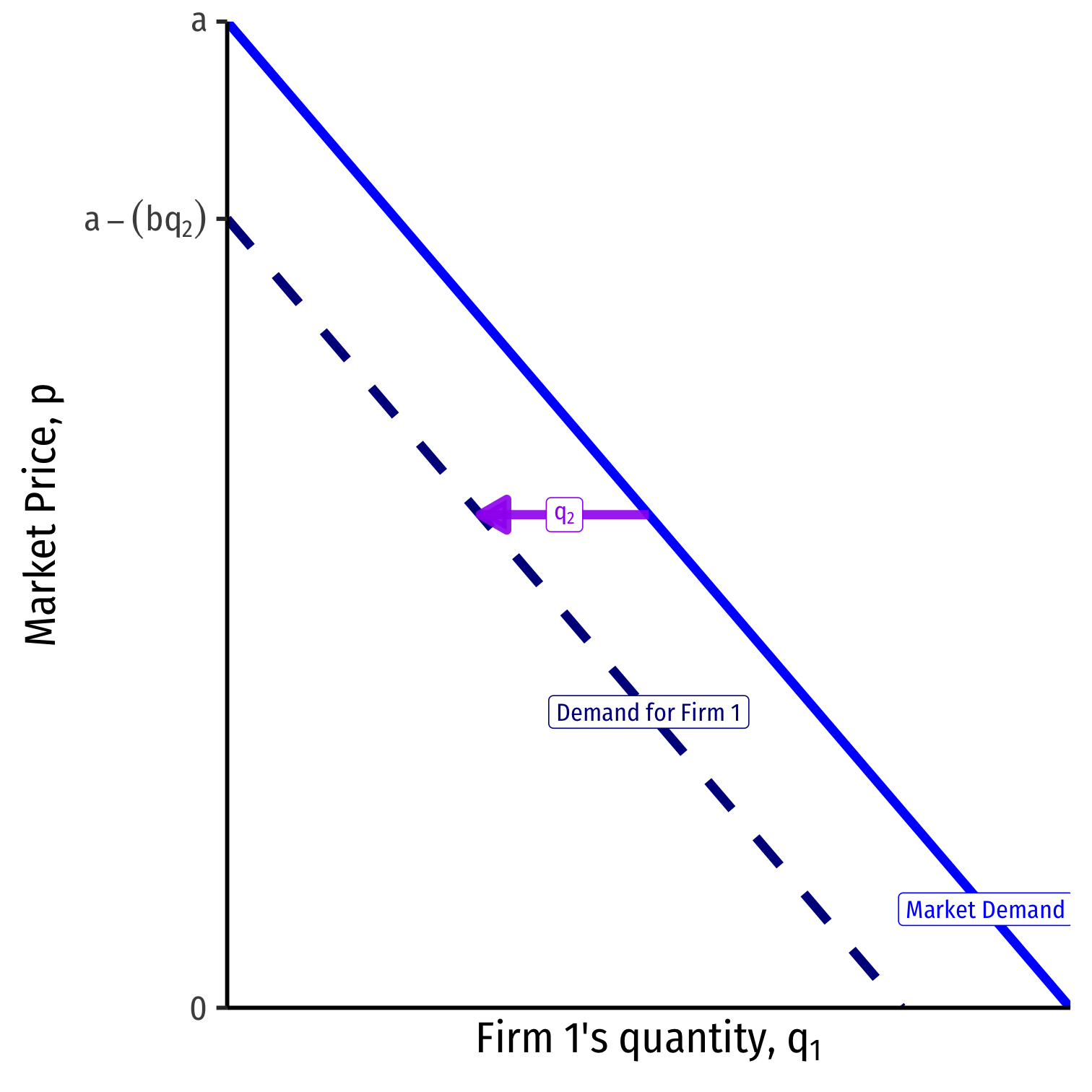

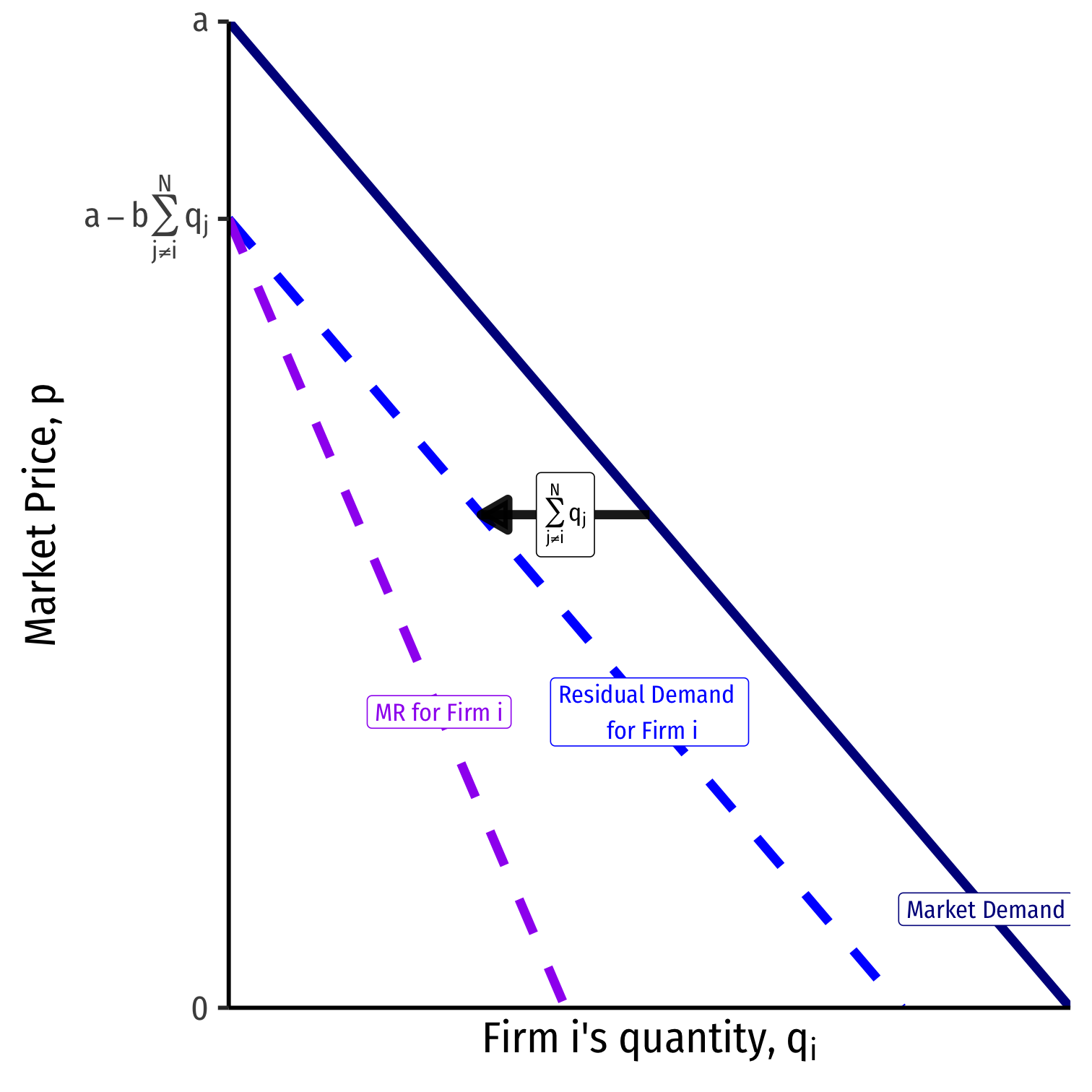

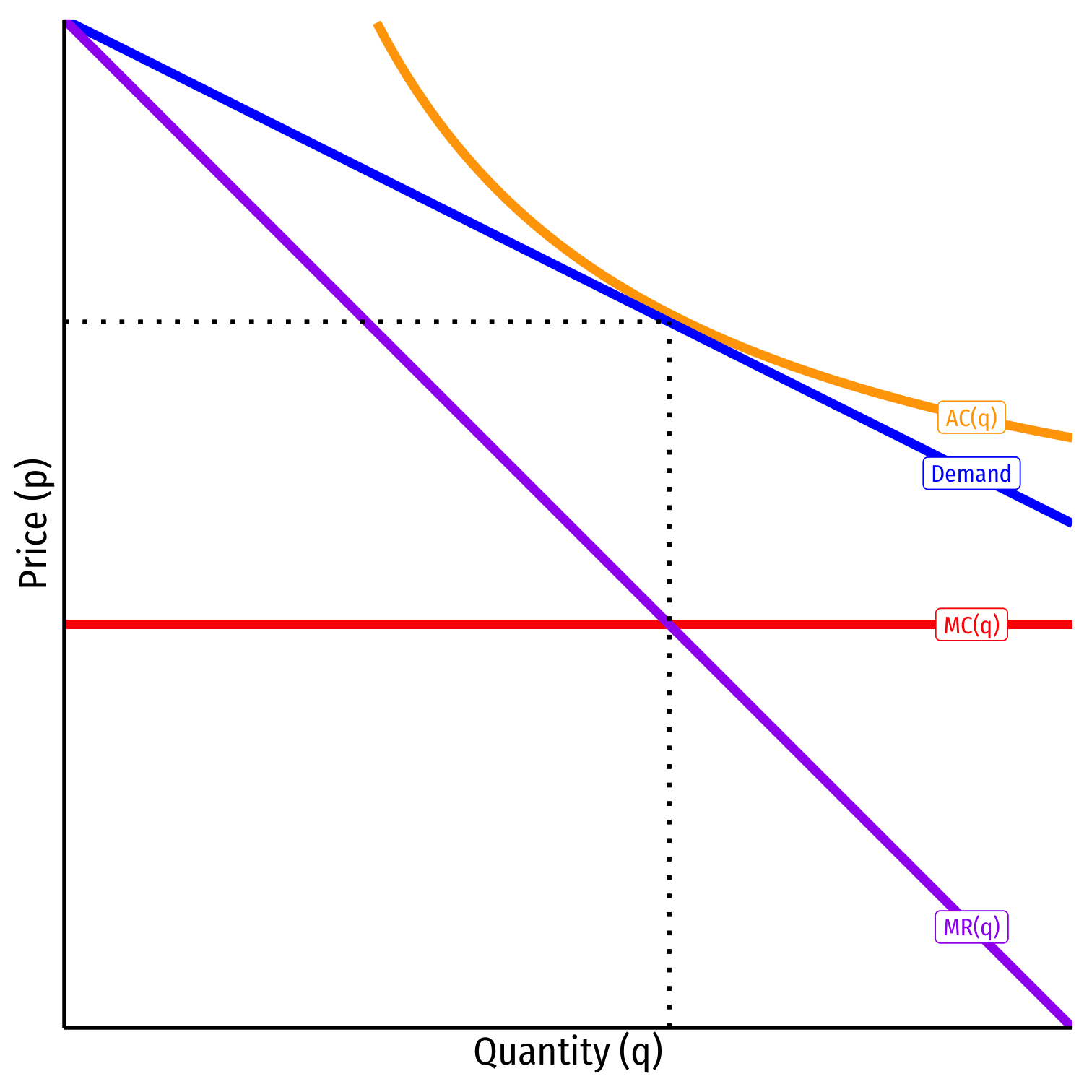

Residual Demand

- Consider the demand each firm faces to be a residual demand

Residual Demand

Consider the demand each firm faces to be a residual demand

e.g. for firm 1, it's (residual) demand is:

Residual Demand

Consider the demand each firm faces to be a residual demand

e.g. for firm 1, it's (residual) demand is:

p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)⏟intercept−b⏟slopeq1p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)intercept−bslopeq1

Residual Demand

Consider the demand each firm faces to be a residual demand

e.g. for firm 1, it's (residual) demand is:

p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)⏟intercept−b⏟slopeq1p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)intercept−bslopeq1

- Firm 2 will produce some amount, q2q2.

Residual Demand

Consider the demand each firm faces to be a residual demand

e.g. for firm 1, it's (residual) demand is:

p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)⏟intercept−b⏟slopeq1p=a−b(q1+q2)p=(a−bq2)intercept−bslopeq1

Firm 2 will produce some amount, q2q2.

Firm 1 takes this as given, to find its own residual demand

- Intercept: a−bq2a−bq2

- Slope: bb (coefficient in front of q1)q1)

Residual Demand

Firm 2 will produce some amount, q2q2.

Firm 1 will take this as a given, a constant

Firm 1's choice variable is q1q1, given q2q2

Cournot Competition: Example

Example: Assume Coke (c)(c) and Pepsi (p)(p) are the only two cola producers, each with a constant MC=AC=$0.50. The market (inverse) demand curve is given by: P=5−0.05QQ=qc+qpP=5−0.05QQ=qc+qp

Cournot Competition: Example

Example: Assume Coke (c)(c) and Pepsi (p)(p) are the only two cola producers, each with a constant MC=AC=$0.50. The market (inverse) demand curve is given by: P=5−0.05QQ=qc+qpP=5−0.05QQ=qc+qp

P=5−0.05QP=5−0.05Q

Cournot Competition: Example

Example: Assume Coke (c)(c) and Pepsi (p)(p) are the only two cola producers, each with a constant MC=AC=$0.50. The market (inverse) demand curve is given by: P=5−0.05QQ=qc+qpP=5−0.05QQ=qc+qp

P=5−0.05QP=5−0.05Q

P=5−0.05qc−0.05qpP=5−0.05qc−0.05qp

Cournot Competition: Example

P=5−0.05qc−0.05qpP=5−0.05qc−0.05qp

Cournot Competition: Example

P=5−0.05qc−0.05qpP=5−0.05qc−0.05qp

- Firms maximize profit (as always), by setting q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)

Cournot Competition: Example

P=5−0.05qp⏟intercept−0.05⏟slopeqcP=5−0.05qpintercept−0.05slopeqc

Firms maximize profit (as always), by setting q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)

Solve for Coke’s MR(q) first:

- Take qpqp as given, a constant

- Recall MR is twice the slope of demand

Cournot Competition: Example

P=5−0.05qp⏟intercept−0.05⏟slopeqcP=5−0.05qpintercept−0.05slopeqc

Firms maximize profit (as always), by setting q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)q∗:MR(q)=MC(q)

Solve for Coke’s MR(q) first:

- Take qpqp as given, a constant

- Recall MR is twice the slope of demand

MRc=5−0.05qp−0.10qcMRc=5−0.05qp−0.10qc

Cournot Competition: Example

Solve for q∗q∗ for each firm (where MR(q)=MC(q))MR(q)=MC(q)), we derive each firm's reaction function or best response function to the other firm's output

Symmetric marginal costs and marginal revenues

Cournot Competition: Example

Solve for q∗q∗ for each firm (where MR(q)=MC(q))MR(q)=MC(q)), we derive each firm's reaction function or best response function to the other firm's output

Symmetric marginal costs and marginal revenues

q∗c=45−0.5qpq∗p=45−0.5qcq∗c=45−0.5qpq∗p=45−0.5qc

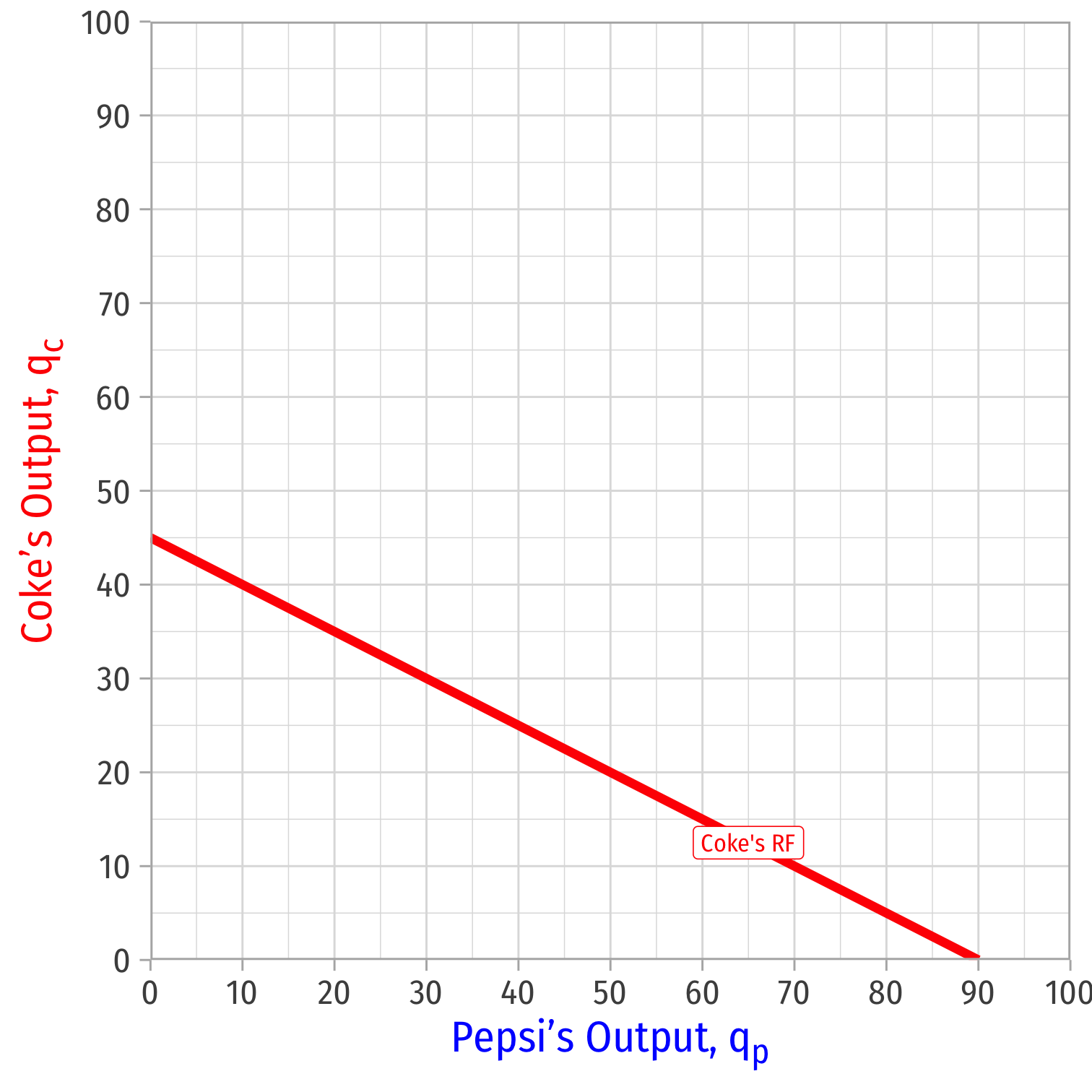

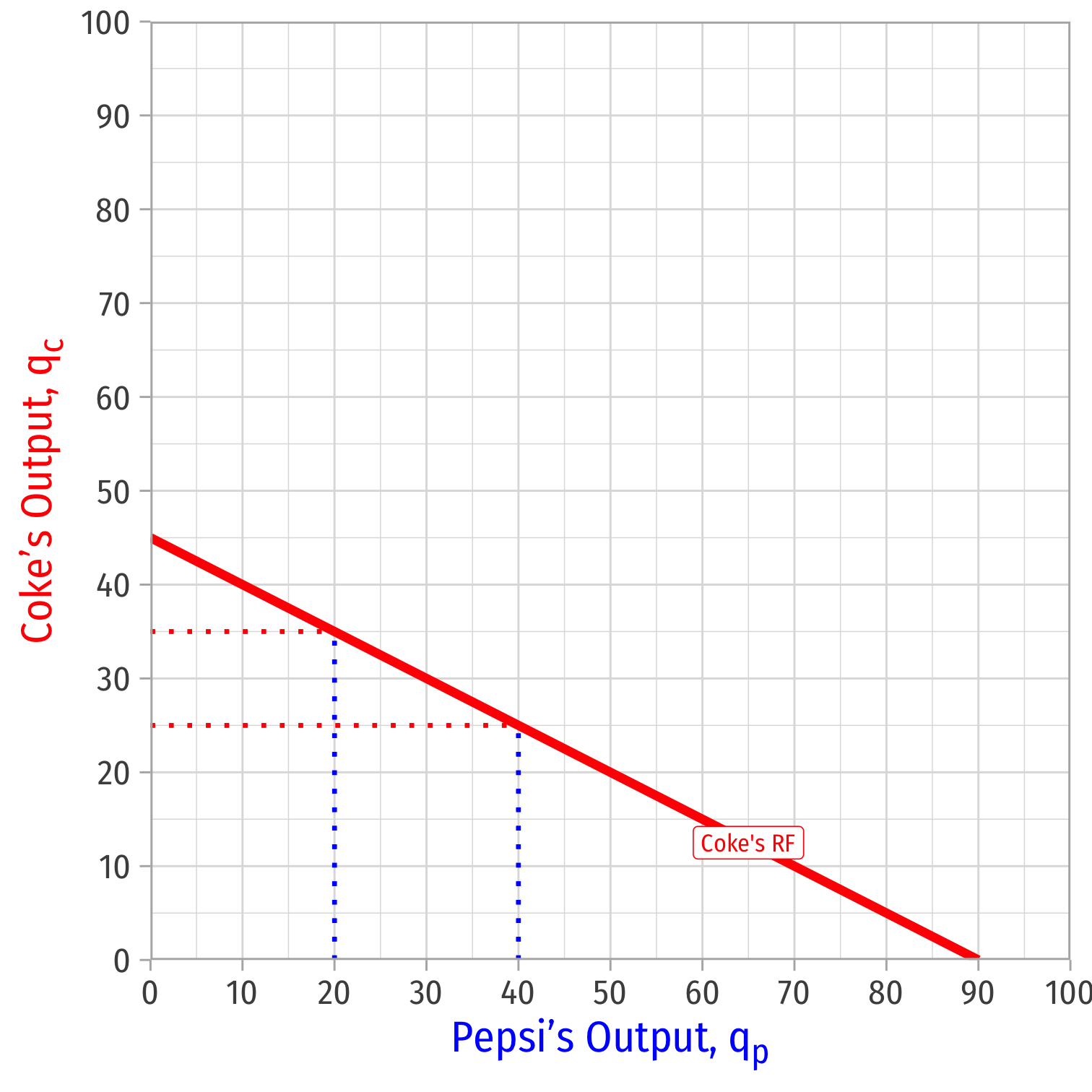

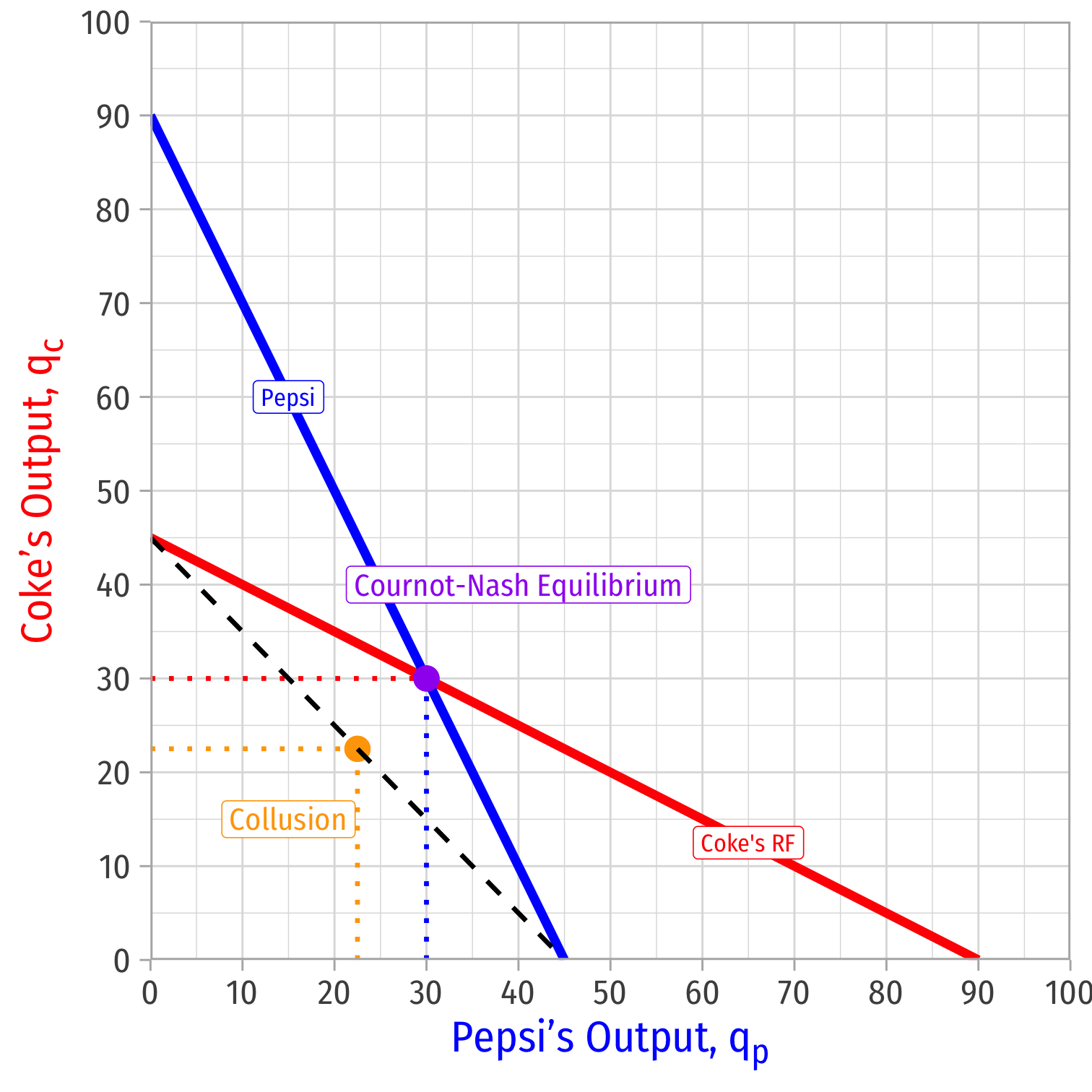

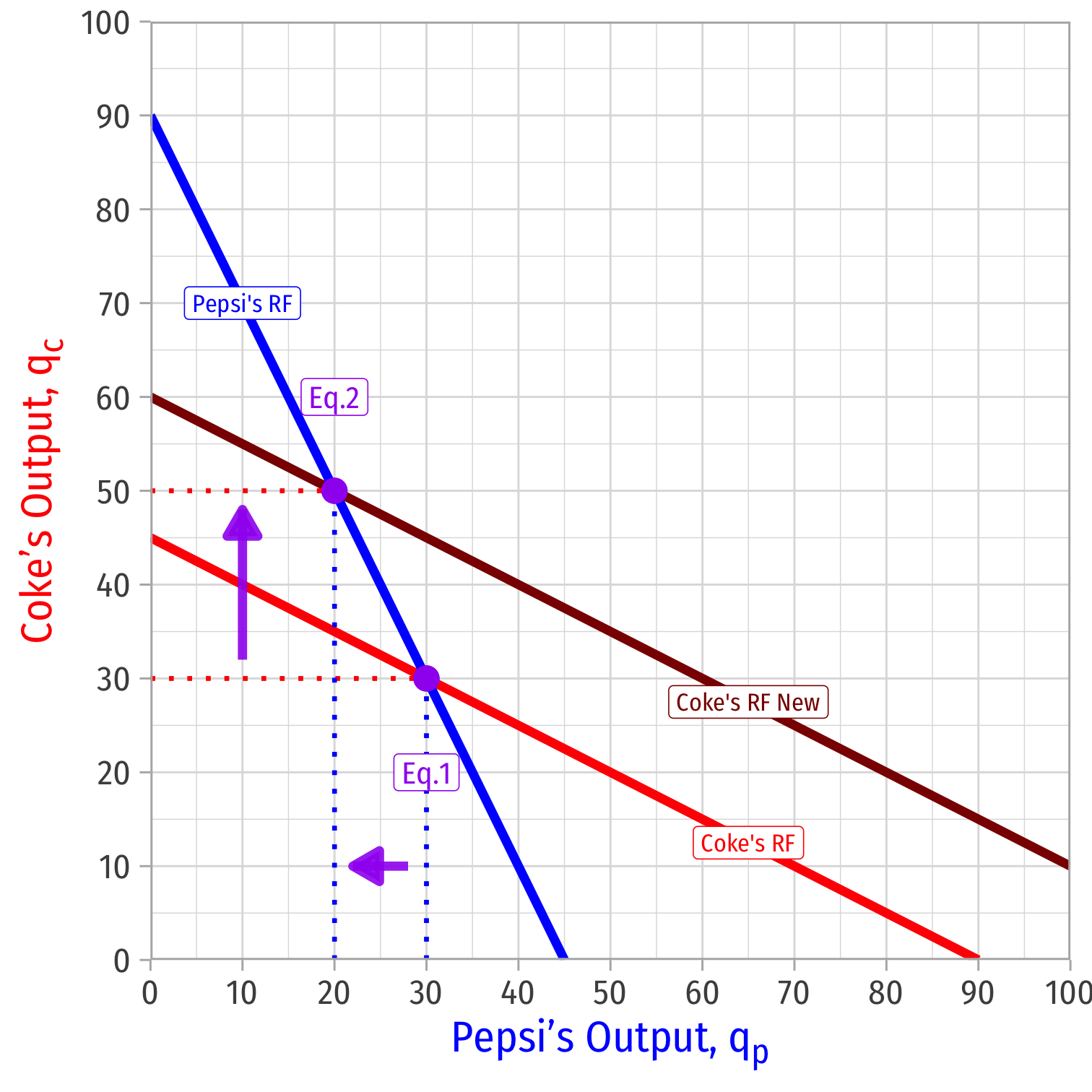

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's output

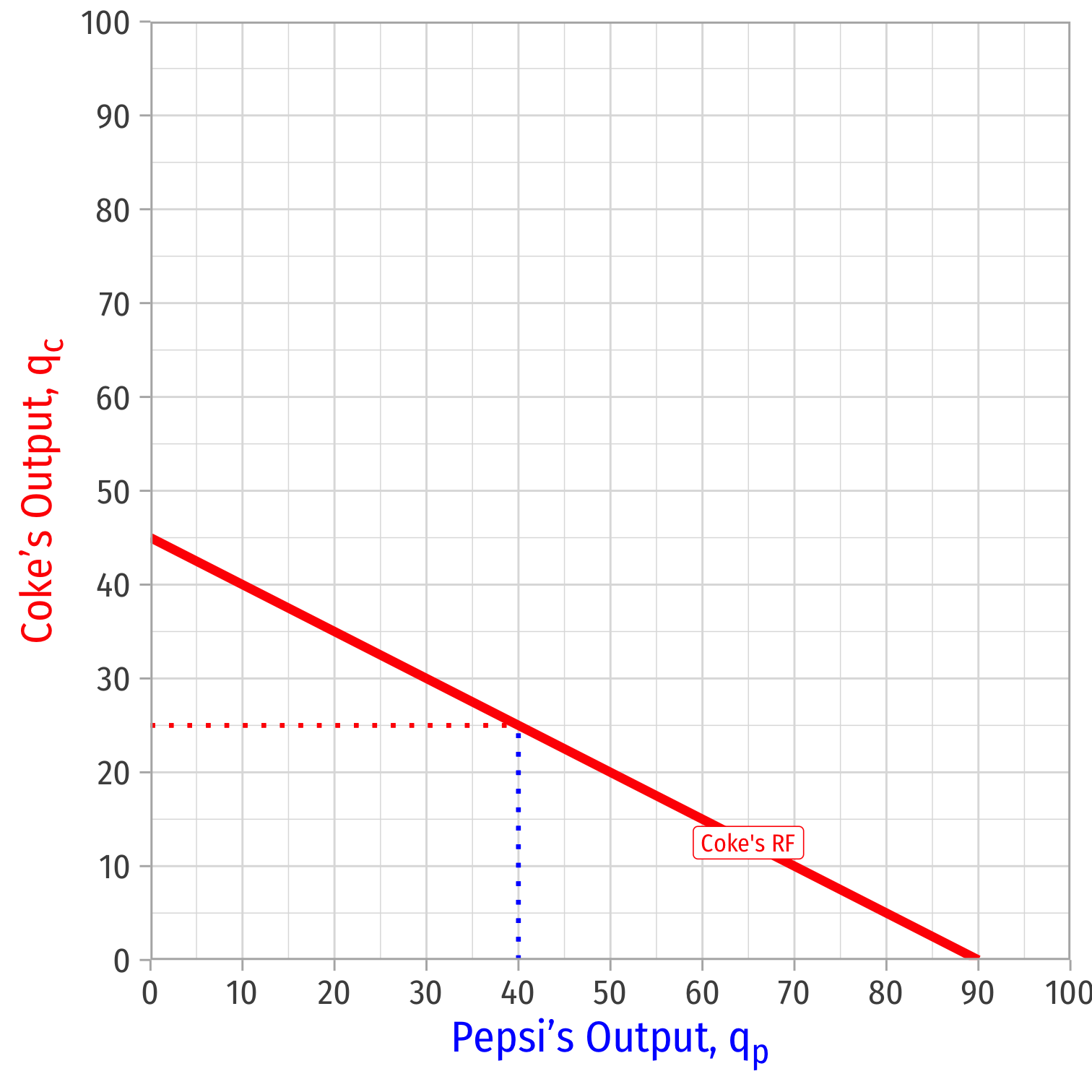

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's output

- e.g. if Pepsi produces 40, Coke's best response is 25

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's output

- e.g. if Pepsi produces 40, Coke's best response is 25

- e.g. if Pepsi produces 20, Coke's best response is 35

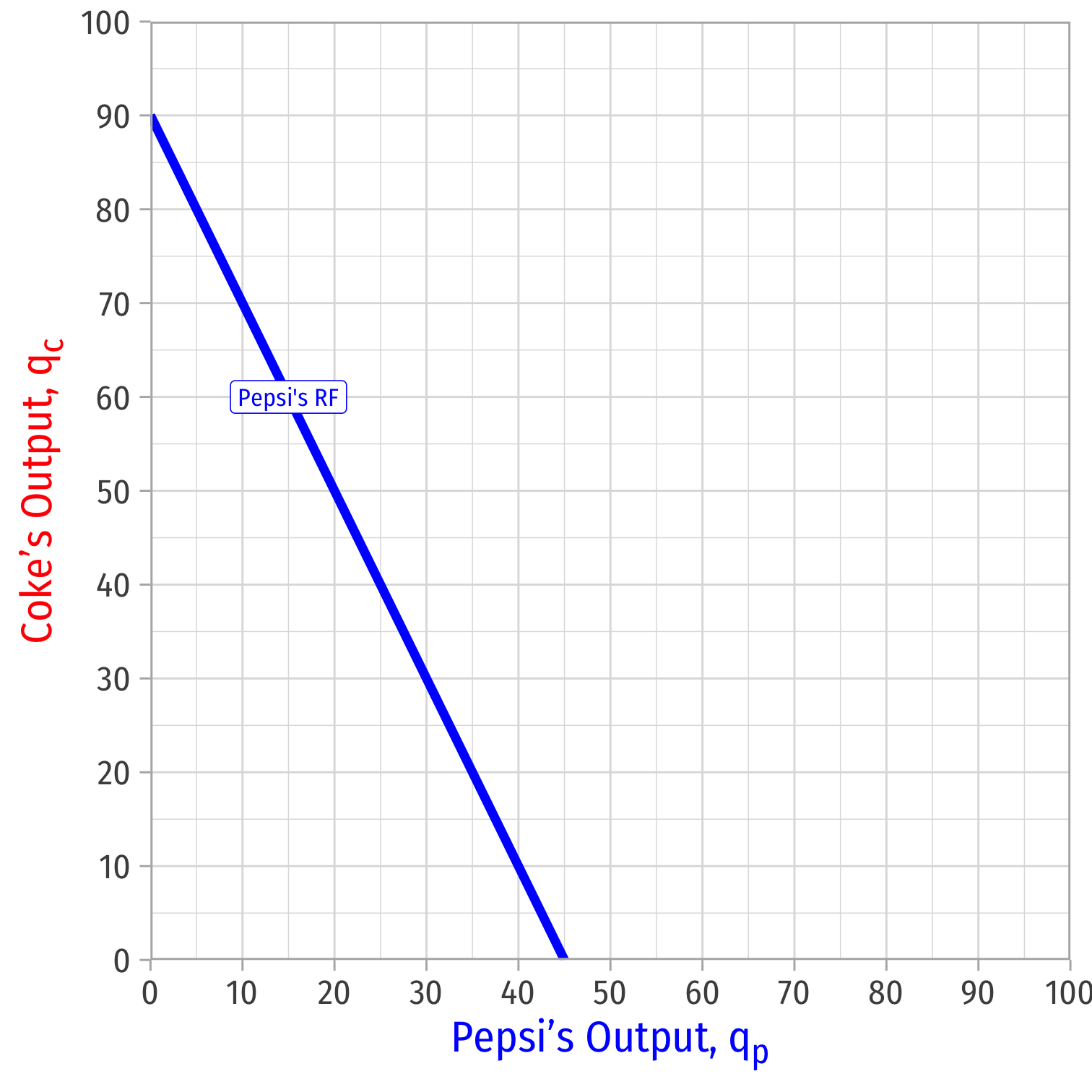

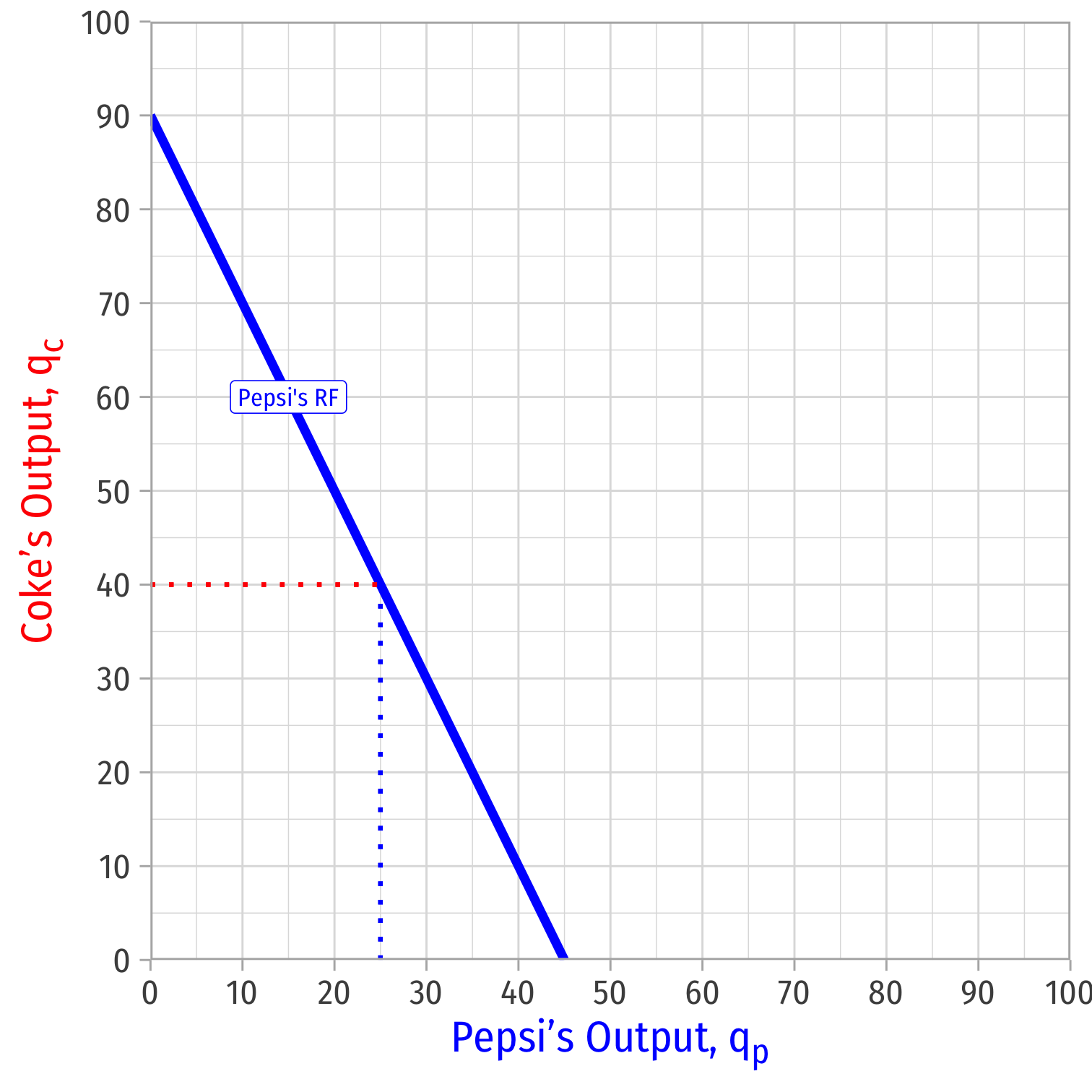

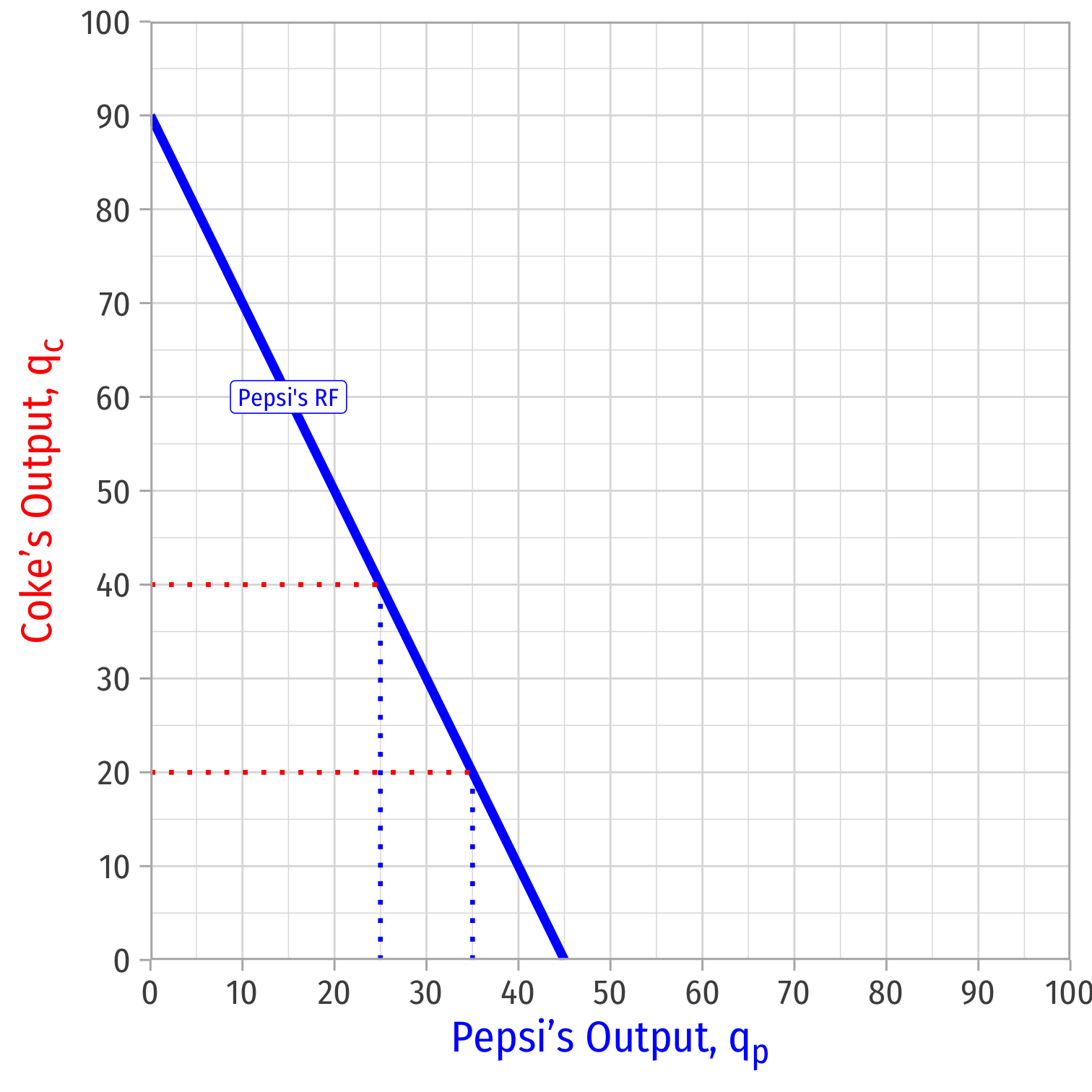

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's output

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's output

- e.g. if Coke produces 40, Pepsi's best response is 25

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's output

- e.g. if Coke produces 40, Pepsi's best response is 25

- e.g. if Coke produces 20, Pepsi's best response is 35

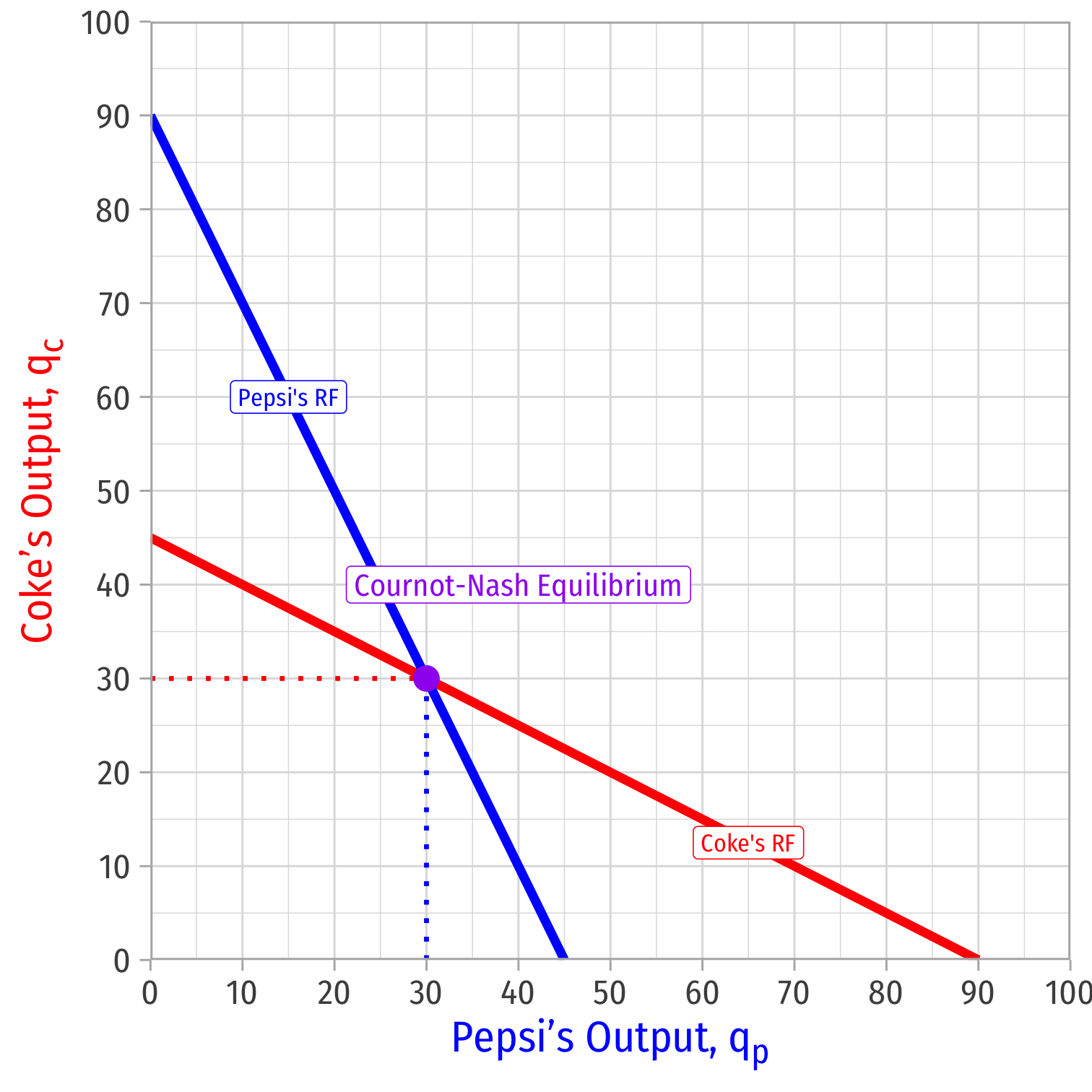

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Graphically

Combine both curves on the same graph

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium: (30,30)(30,30)

- Where both reaction curves intersect

Both are playing mutual best response to one another

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Cournot-Nash Equilibrium algebraically: plug one firm's reaction function into the other's

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Cournot-Nash Equilibrium algebraically: plug one firm's reaction function into the other's

q∗c=30−0.5qpq∗p=30−0.5qcq∗c=30−0.5qpq∗p=30−0.5qc

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Cournot-Nash Equilibrium algebraically: plug one firm's reaction function into the other's

q∗c=30−0.5qpq∗p=30−0.5qcq∗c=30−0.5qpq∗p=30−0.5qc

- The market demand again was

P=5−0.05qc−0.05qpP=5−0.05qc−0.05qp

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

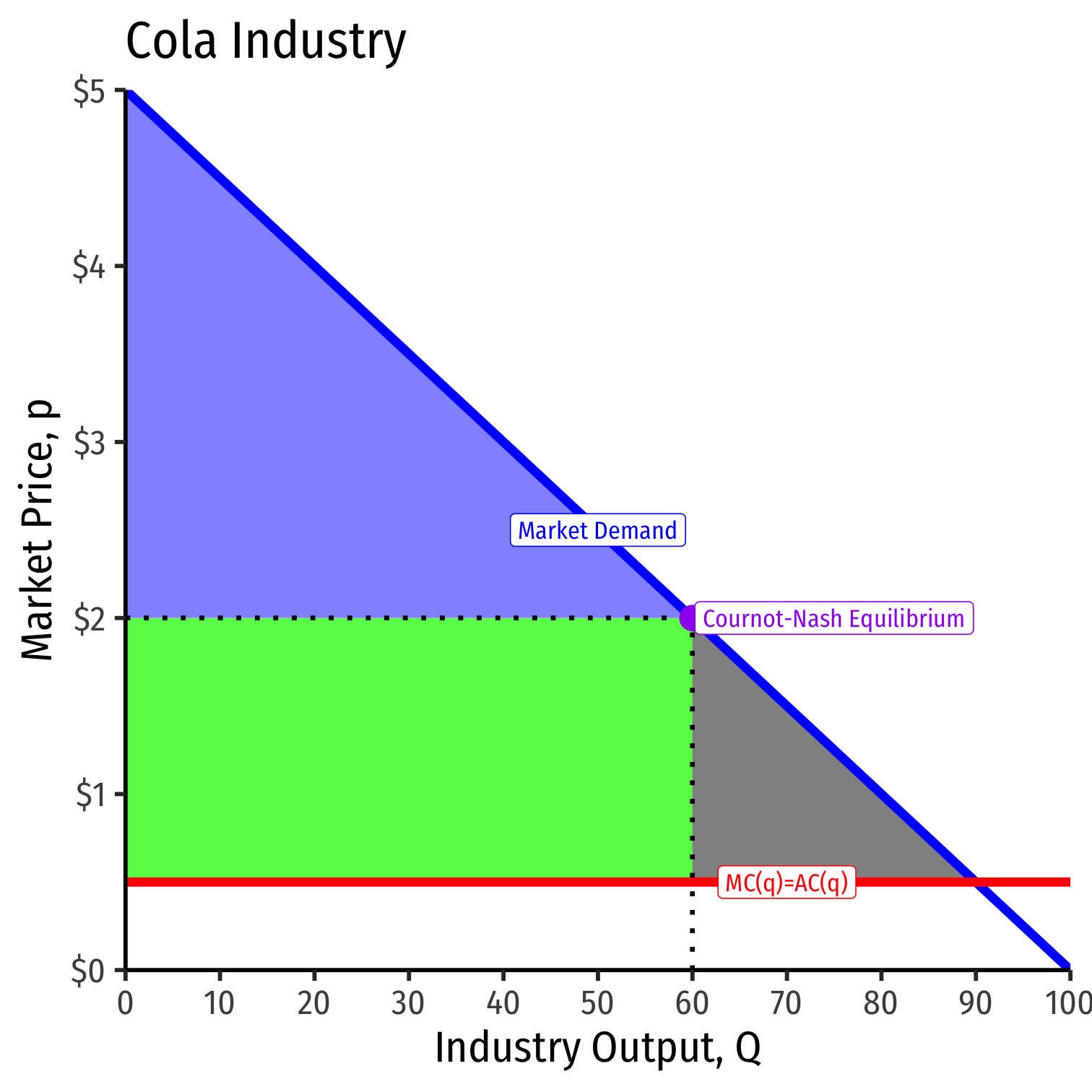

- Both firms produce 30

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Both firms produce 30

P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Both firms produce 30

P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00

- Find profit for each firm:

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, Algebraically

- Both firms produce 30

P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00P=5−0.05(30+30)P=$2.00

- Find profit for each firm:

πc=qc(P−c)πc=30(2.00−0.50)πc=45πc=qc(P−c)πc=30(2.00−0.50)πc=45

- Symmetrically for Pepsi, πp=45πp=45

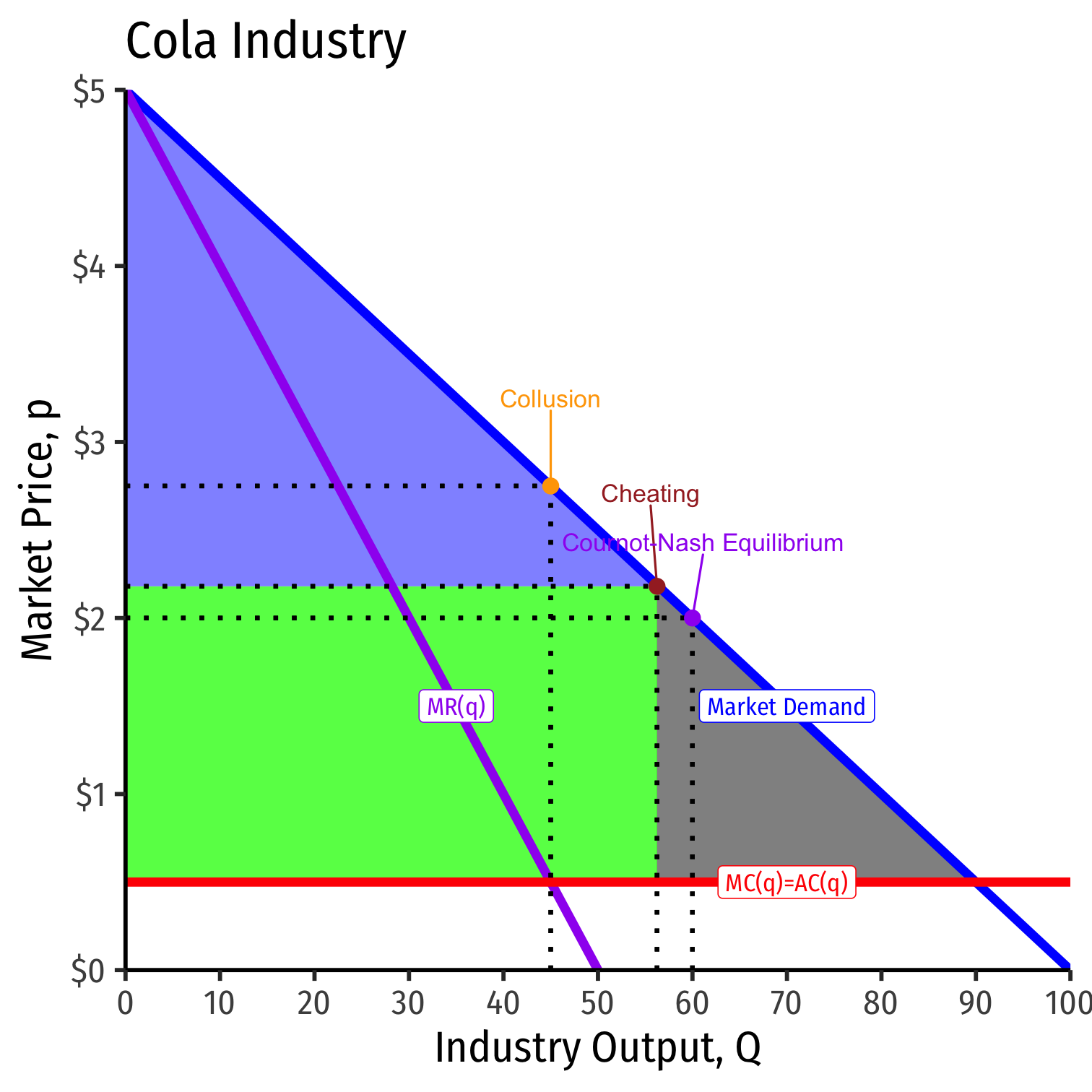

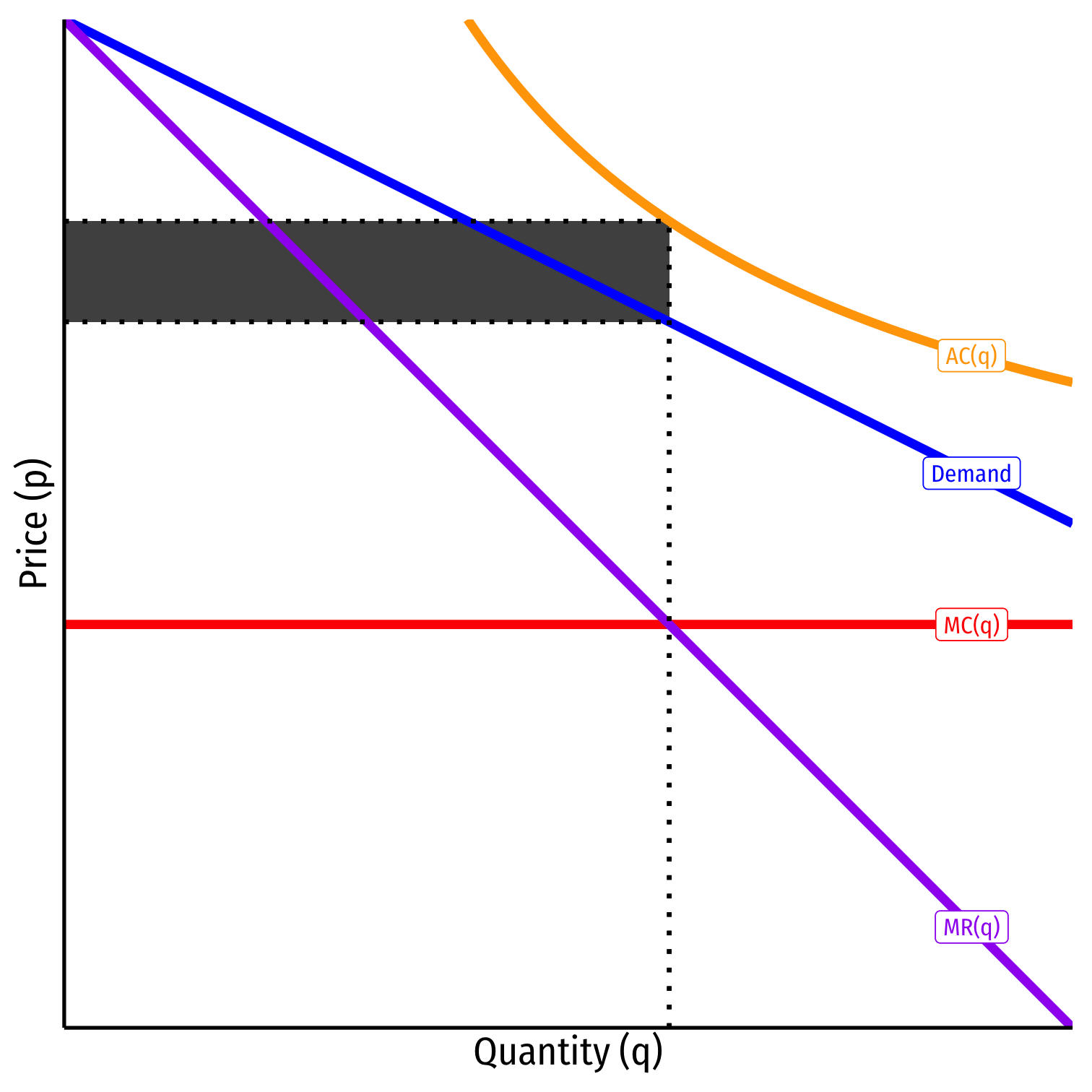

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium, The Market

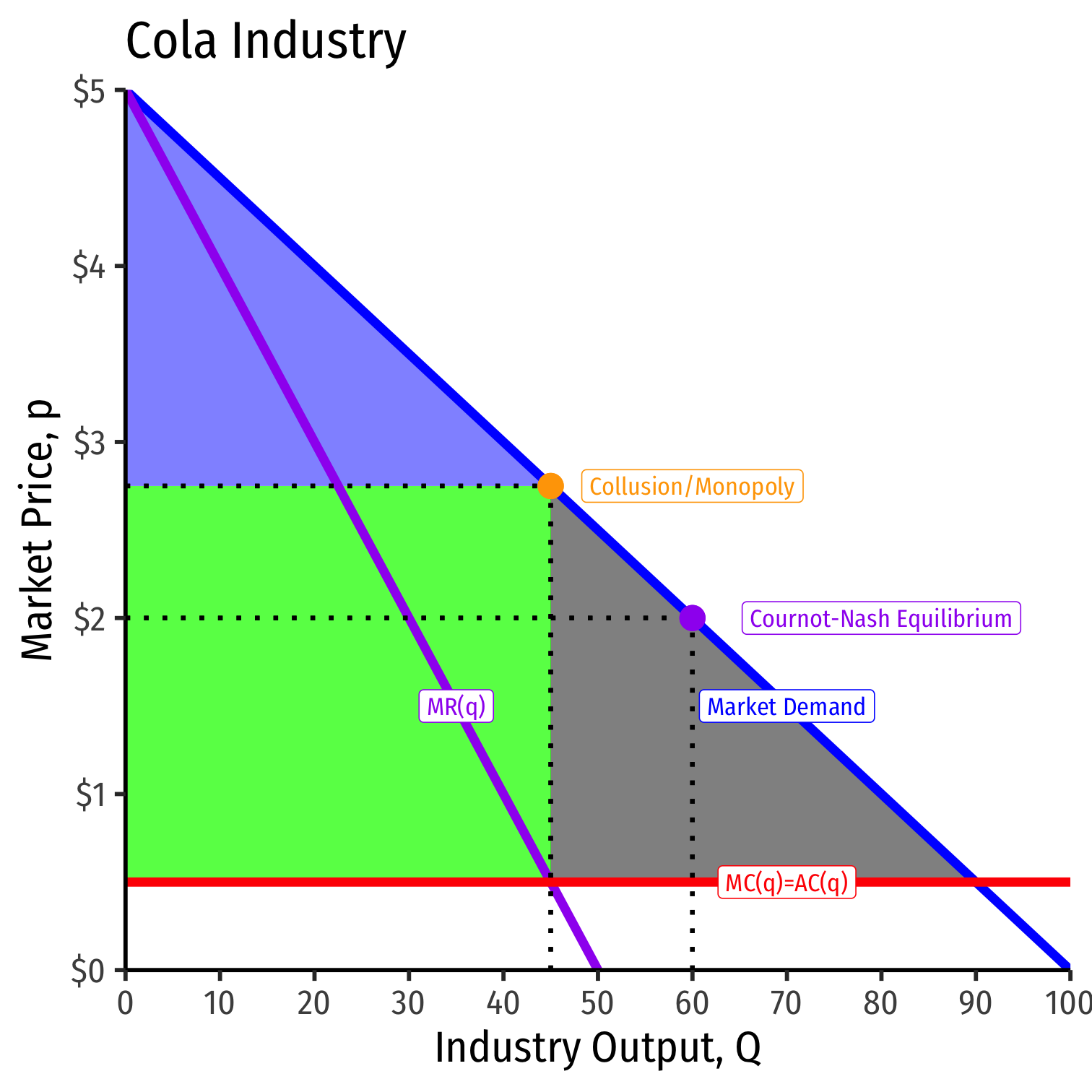

Cournot Collusion

- Suppose now both firms collude to act like a monopolist, who sets the entire market:

MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗

Cournot Collusion

- Suppose now both firms collude to act like a monopolist, who sets the entire market:

MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗

- The monopoly price will then be:

P=5−0.05(45)P=$2.75P=5−0.05(45)P=$2.75

Cournot Collusion

- Suppose now both firms collude to act like a monopolist, who sets the entire market:

MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗MR=MC5−0.1Q=0.5045=Q∗

- The monopoly price will then be:

P=5−0.05(45)P=$2.75P=5−0.05(45)P=$2.75

- Total profit will then be:

Π=45($2.75−$0.50)=$101.25Π=45($2.75−$0.50)=$101.25

with $50.625 going to each firm

Cournot Collusion, The Market

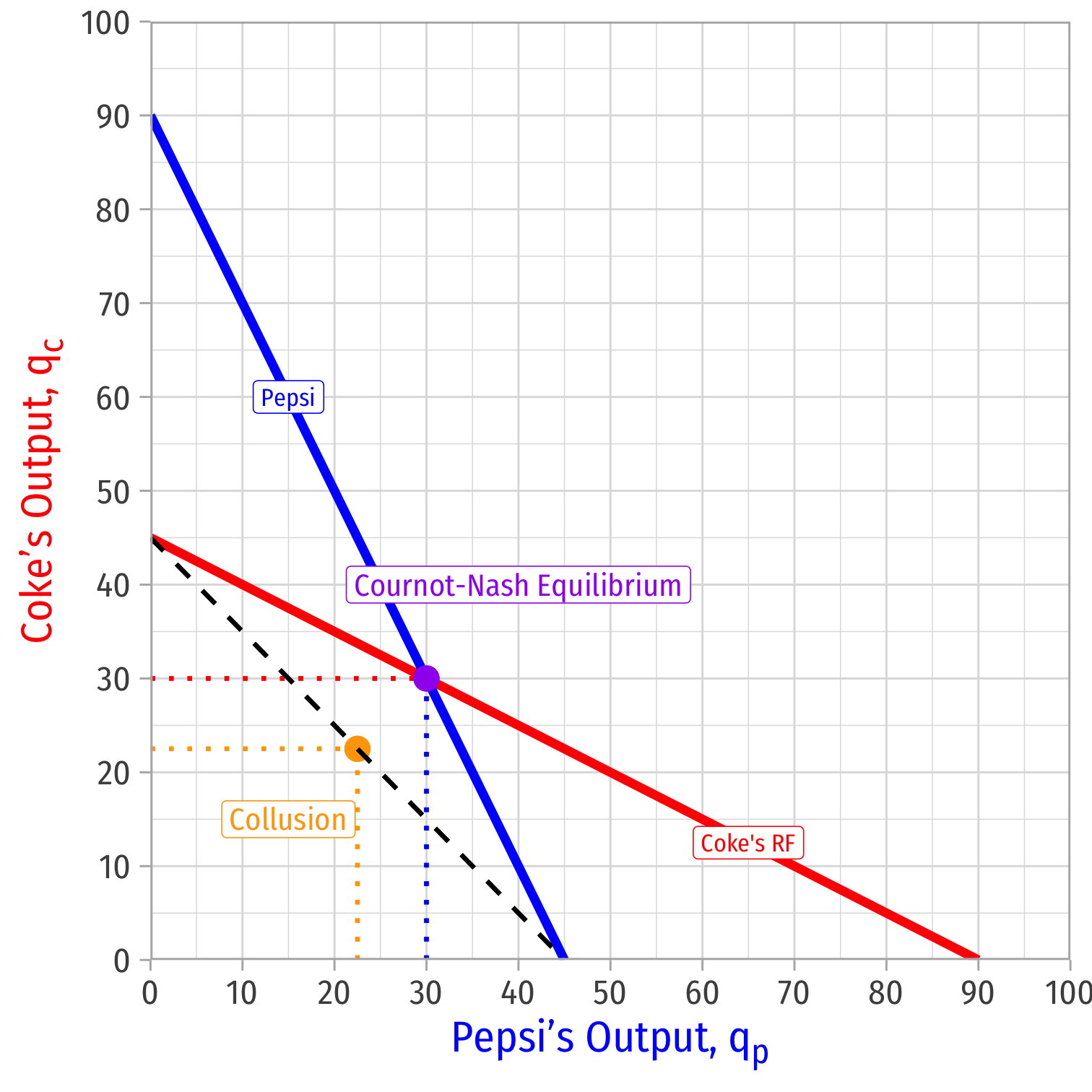

Cournot Collusion

Cournot Competition: each firm produces 30 and earns $45.00

Collusion/Monopoly: each firm produces 22.5 and earns $50.63

Cournot Collusion: Stability

Cournot Competition: each firm produces 30 and earns $45.00

Collusion/Monopoly: each firm produces 22.5 and earns $50.63

But is collusion a Nash equilibrium?

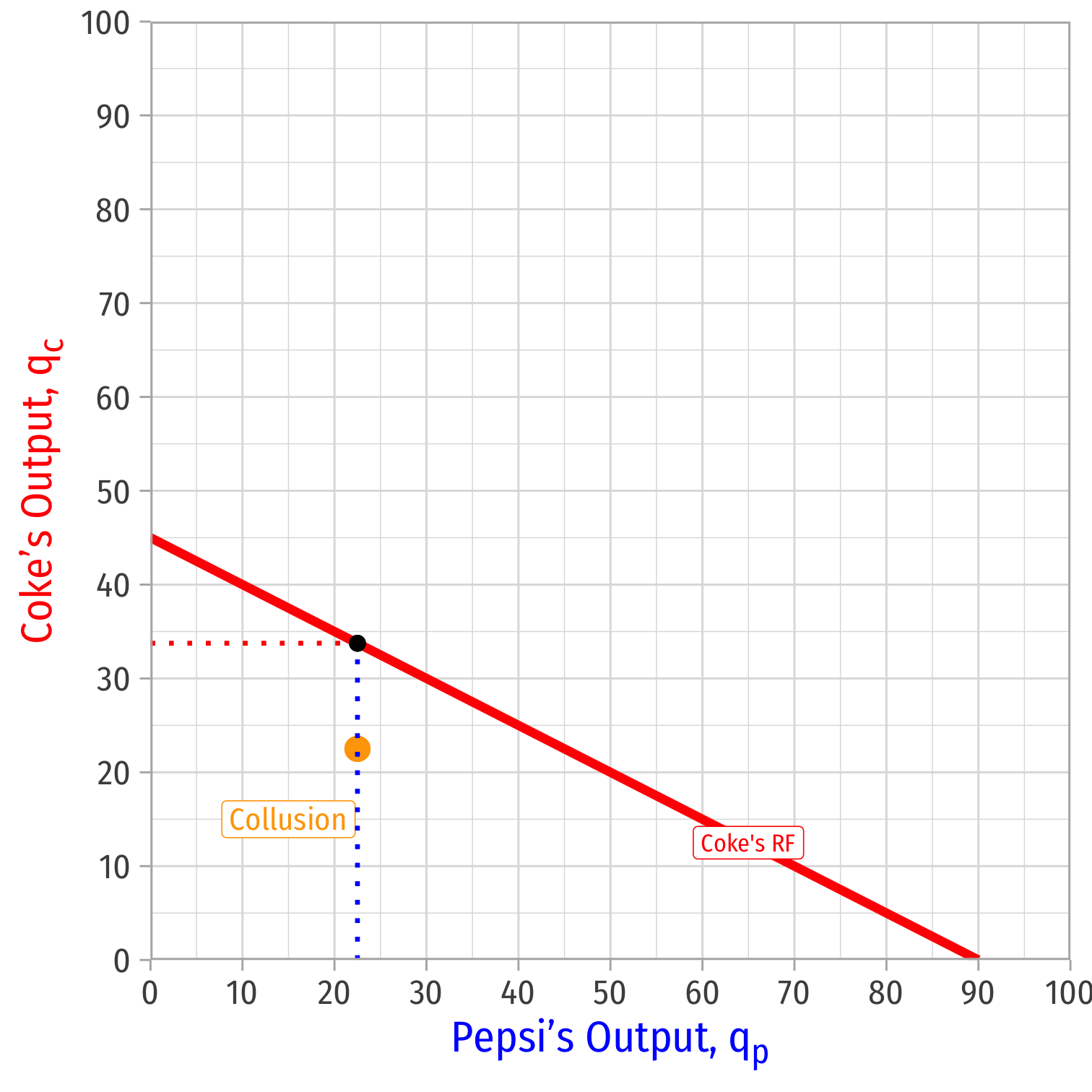

Cournot Collusion: Stability

Read either firm's reaction curve at the collusive outcome

Suppose Coke knows Pepsi is producing 22.5 (as per the cartel agreement)

Coke's best response to Pepsi's 22.5 is to produce 33.75

Cournot Collusion: Stability

- This (cheating the agreement) would bring market price to P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875

Cournot Collusion: Stability

- This (cheating the agreement) would bring market price to P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875

- Coke's profit would be:

πc=qc(P−c)πc=33.75(2.1875−0.50)πc=$56.95πc=qc(P−c)πc=33.75(2.1875−0.50)πc=$56.95

Cournot Collusion: Stability

- This (cheating the agreement) would bring market price to P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875P=5−0.05(qc+qp)P=5−0.05∗(33.75+22.50)P=5−0.05∗(56.25)P=$2.1875

- Coke's profit would be:

πc=qc(P−c)πc=33.75(2.1875−0.50)πc=$56.95πc=qc(P−c)πc=33.75(2.1875−0.50)πc=$56.95

- Pepsi's profit would be:

πp=qp(P−c)πp=22.5(2.1875−0.50)πp=$37.97πp=qp(P−c)πp=22.5(2.1875−0.50)πp=$37.97

Cournot Collusion (One Firm Cheating), The Market

Cournot Competition, You Try

Example: Suppose Firm 1 and Firm 2 have a constant MC=AC=8MC=AC=8. The market (inverse) demand curve is given by:

P=200−2QQ=q1+q2P=200−2QQ=q1+q2

Find the Cournot-Nash equilibrium output and profit for each firm.

Find the output and profit for each firm if the two were to collude.

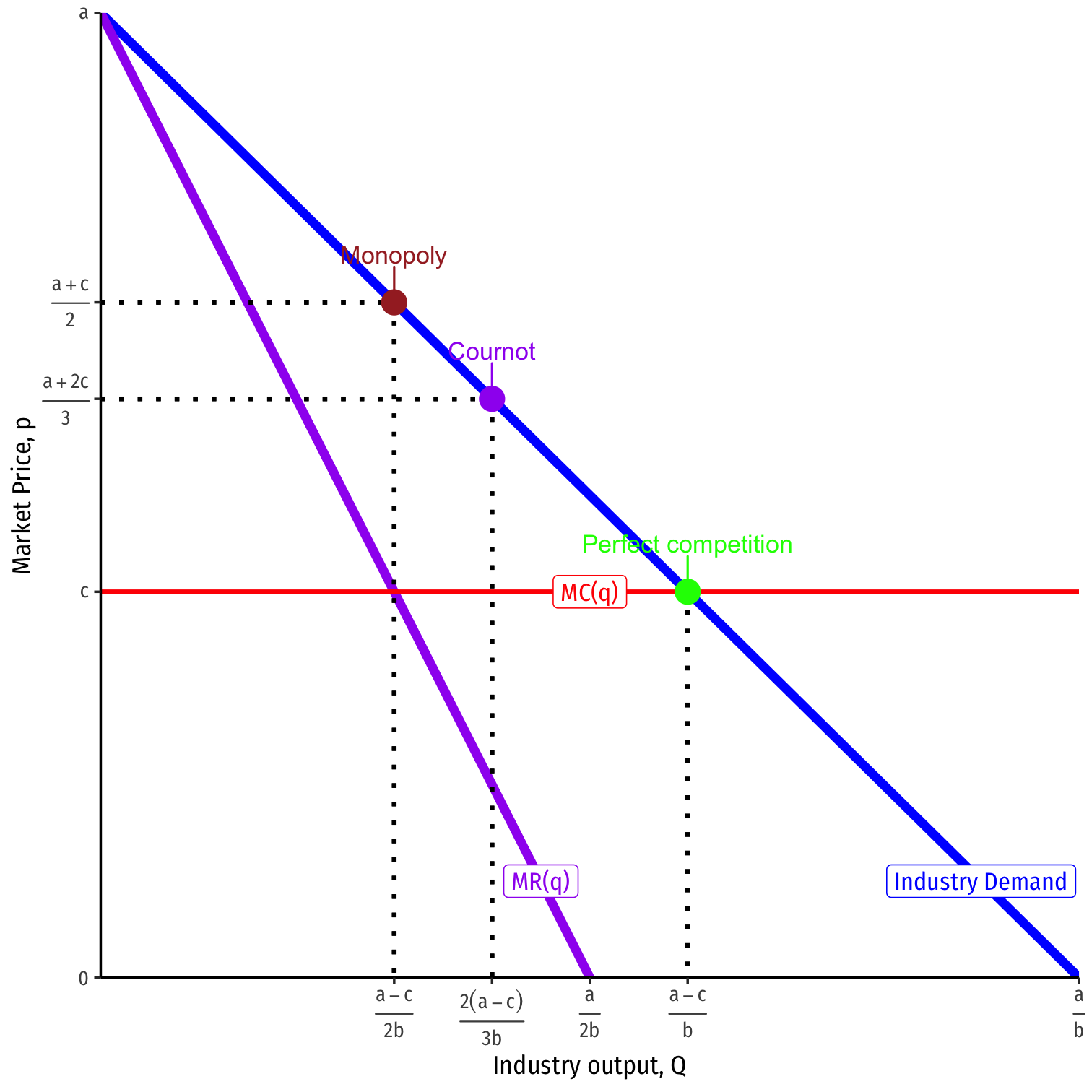

Cournot Equilibrium, In General

- Linear (inverse) demand curve: P=a−bQ(Q=q1+q2)P=a−bQ(Q=q1+q2)

- Constant costs C(q)=cC(q)=c

- Cournot competition:

- q∗1=q∗2=a−c3bq∗1=q∗2=a−c3b

- Q=2(a−c3b)Q=2(a−c3b)

- P=a+2c3P=a+2c3

- π1=π2=(a−c)29bπ1=π2=(a−c)29b

- Monopoly (collusion)

- Q=a−c2bQ=a−c2b

- P=a+c2P=a+c2

- Π=(a−c)24bΠ=(a−c)24b

Comparative Statics

- What if we relax some assumptions about the model?

- Same technology (same costs)

- Two firms only

- No fixed costs

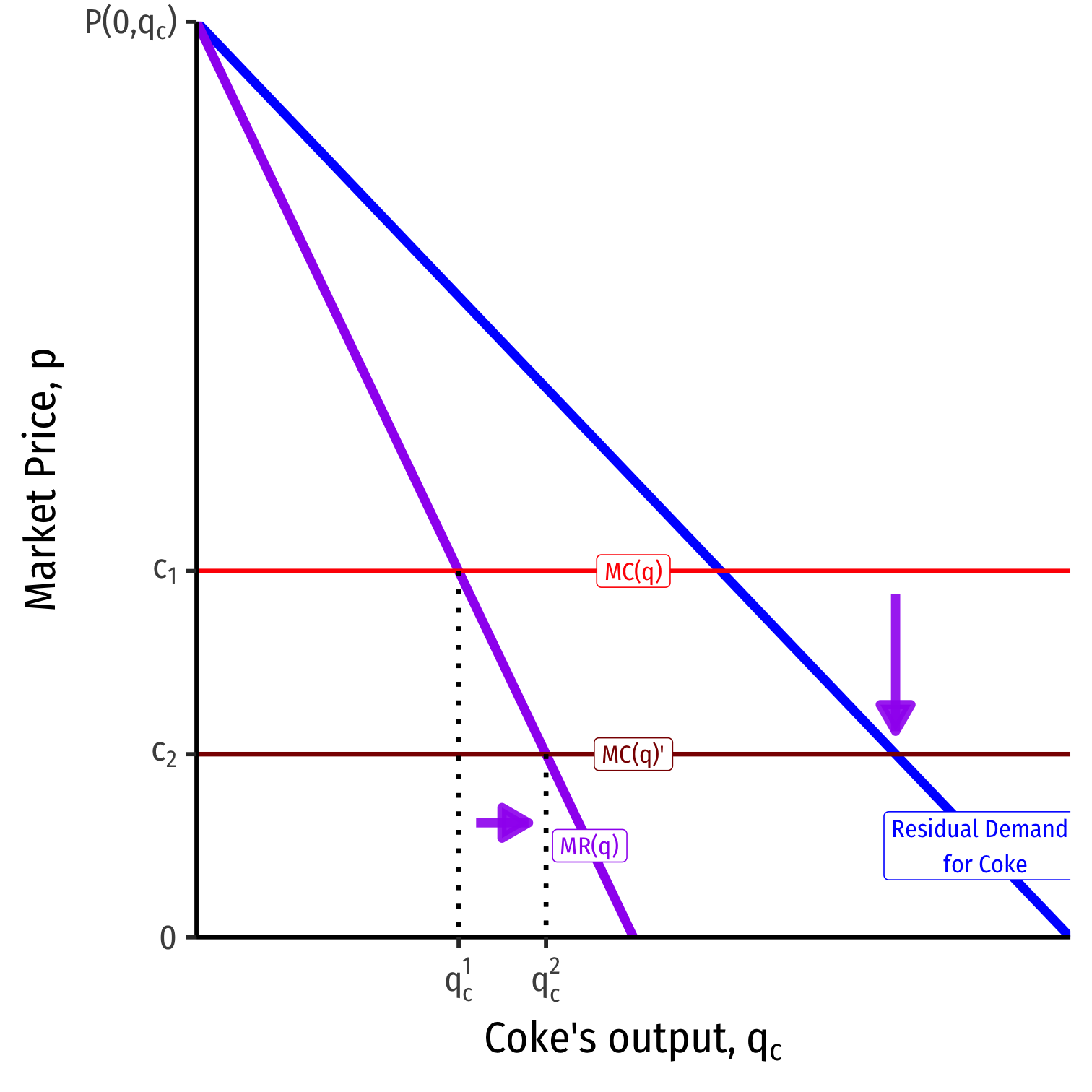

Comparative Statics: Decrease in MC

Suppose Coke's marginal cost decreases (such that MCc<MCpMCc<MCp)

Profit maximization requires MCc=MRcMCc=MRc, so it will produce more (at q2cq2c)

Comparative Statics: Increase in MR

Or equivalently, suppose Coke's marginal revenue increases (such that MRc>MRpMRc>MRp)

Profit maximization requires MCc=MRcMCc=MRc, so it will produce more (at q2cq2c)

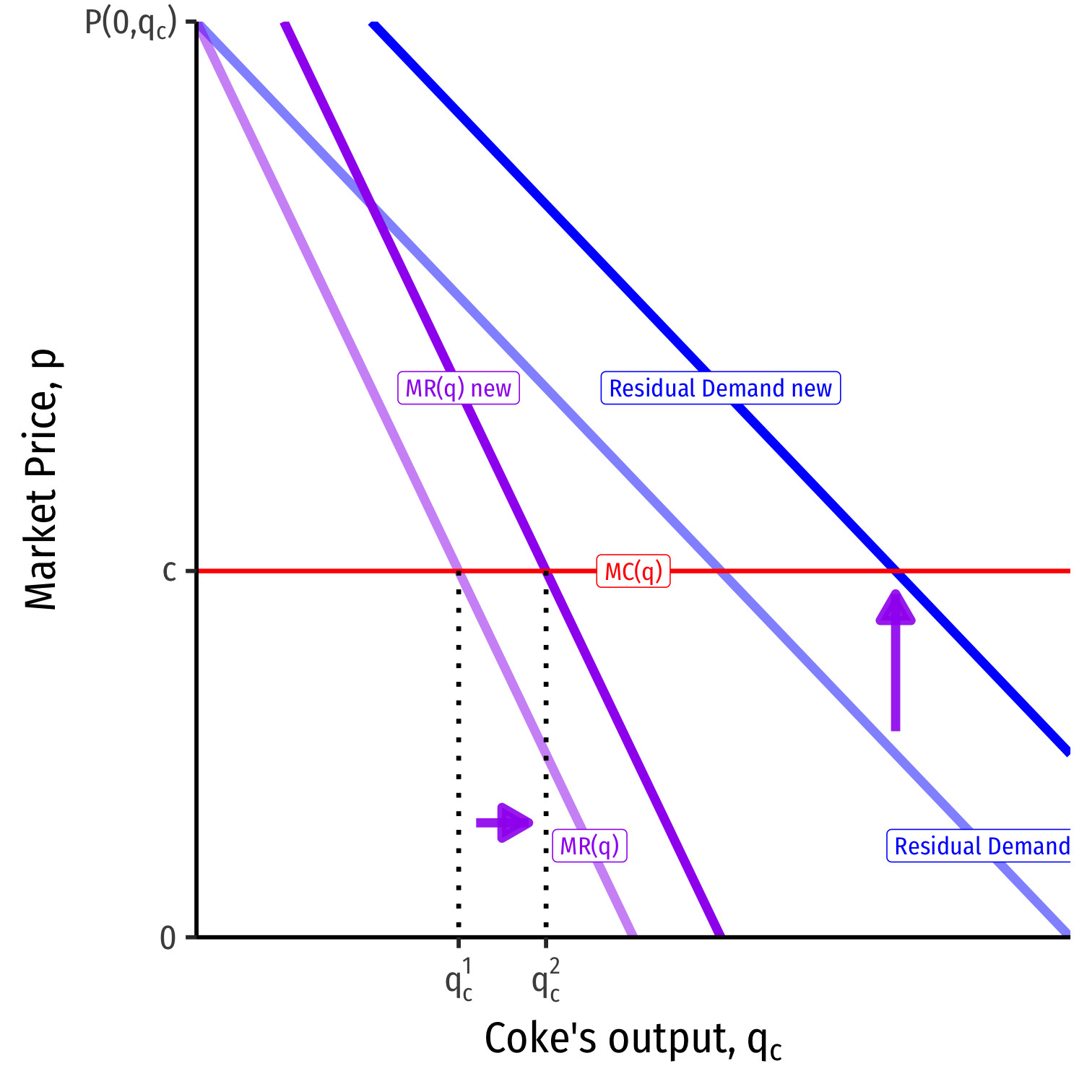

Comparative Statics: Increase in MR

In either case, Coke becomes more efficient than Pepsi (lower cost/higher revenues)

Coke will produce more output

- A shift of its reaction function to the right

Pepsi will produce less output as a response

Overall industry output increases; price decreases

Profits to Coke increase; profits to Pepsi decrease

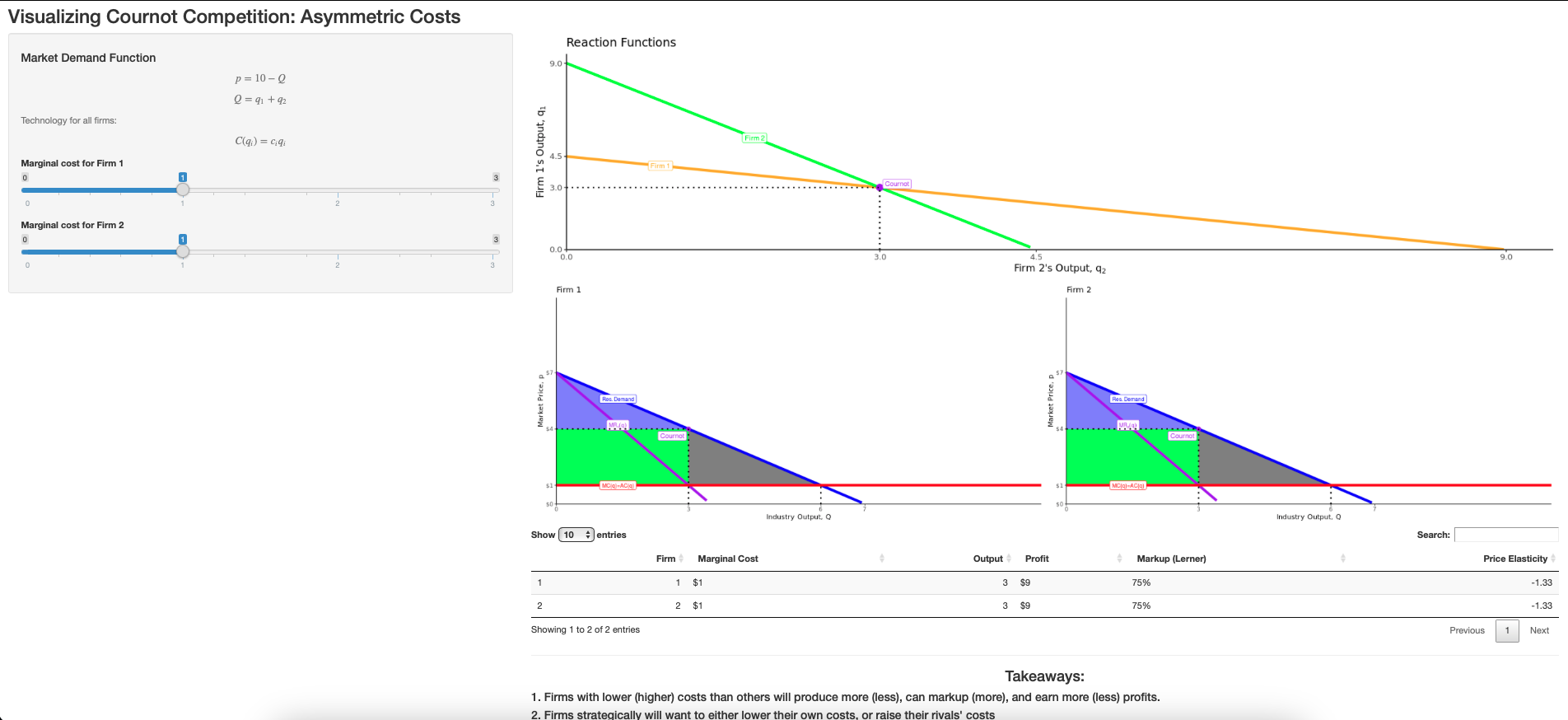

Cournot Competition: Asymmetric Firms

If a firm has lower costs/higher revenues than others, it earns greater profit

Competing firms will want to:

- lower their own costs/raise revenues

- raise rivals' costs/lower their revenues

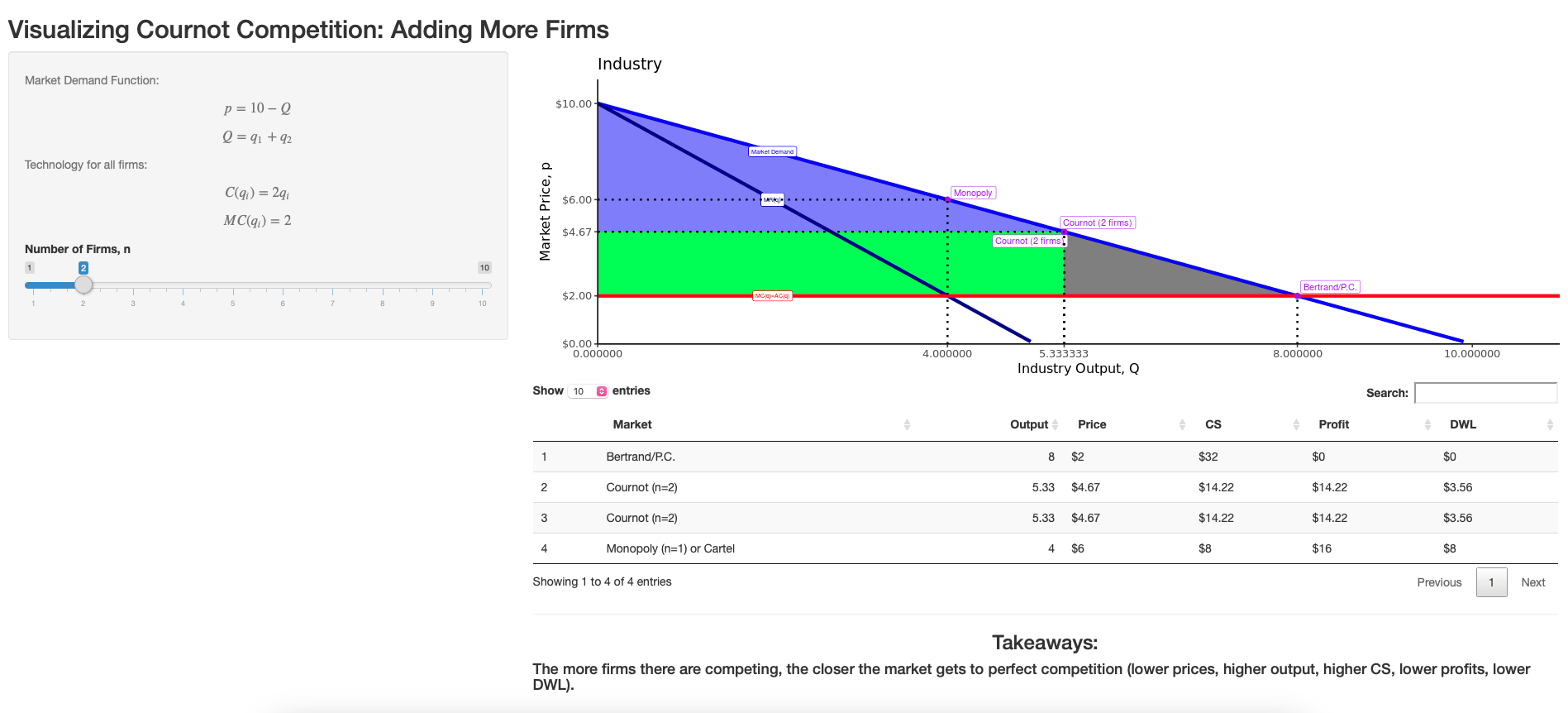

Endogenizing the Number of Firms

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

So far we've assumed the number of firms exogenously: two.

But as in any market, profits will attract entry

Let's make the number of firms endogenous, determined by the market conditions

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

- For tractability, return to our strict assumptions:

- identical technology, costs, revenues

- firms selling perfect substitutes

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

Symmetrically, in equilibrium, each firm will be selling 1N=si1N=si of industry output

- NN number of firms in equilibrium

- sisi is market share of firm ii: (qiQ)(qiQ)

e.g. with 5 firms, each sells 1515 of QQ, market share of 20% each

Each firm earns profits πi(N)πi(N)

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

- Algebraically, with identical technology, each firm's marginal revenue is

MRi=[a−bN∑j≠iqj]⏟intercept−2bqiMRi=⎡⎣a−bN∑j≠iqj⎤⎦intercept−2bqi

- So in symmetric equilibrium, MRi=MCiMRi=MCi for each firm ii:

a−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=ca−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=c

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

- In equilibrium, each firm is maximizing profits (MRi=MCi)(MRi=MCi):

a−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=ca−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=c

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

- In equilibrium, each firm is maximizing profits (MRi=MCi)(MRi=MCi):

a−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=ca−bN∑j≠iqj−2bqi=c

- Since each firm's equilibrium output qi,qj,⋯,qNqi,qj,⋯,qN will be symmetric:

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

- Solving for q∗q∗:

q∗=a−c(N+1)bq∗=a−c(N+1)b

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

- Solving for q∗q∗:

q∗=a−c(N+1)bq∗=a−c(N+1)b

- Total industry output Q=Nq∗Q=Nq∗, so:

Q∗=N(a−c)(N+1)bQ∗=N(a−c)(N+1)b

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

- Solving for q∗q∗:

q∗=a−c(N+1)bq∗=a−c(N+1)b

- Total industry output Q=Nq∗Q=Nq∗, so:

Q∗=N(a−c)(N+1)bQ∗=N(a−c)(N+1)b

p∗=A+NcN+1p∗=A+NcN+1

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

- Solving for q∗q∗:

q∗=a−c(N+1)bq∗=a−c(N+1)b

- Total industry output Q=Nq∗Q=Nq∗, so:

Q∗=N(a−c)(N+1)bQ∗=N(a−c)(N+1)b

p∗=A+NcN+1p∗=A+NcN+1

πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)

See pp.243-244 of the textbook for algebraic derivations.

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

a−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=ca−b(N−1)q∗−2bq∗=c

- Solving for q∗q∗:

q∗=a−c(N+1)bq∗=a−c(N+1)b

- Total industry output Q=Nq∗Q=Nq∗, so:

Q∗=N(a−c)(N+1)bQ∗=N(a−c)(N+1)b

p∗=A+NcN+1p∗=A+NcN+1

πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)

- Takeaways:

- As the number of firms, N↑N↑: ↓qi↓qi; ↑Q↑Q; ↓p↓p; ↓πi↓πi

- We approach the perfectly competitive equilibrium!

See pp.243-244 of the textbook for algebraic derivations.

Cournot Competition with NN Firms

- Each firm ii’s output, symmetrically, will be such that:

p−MCp=1εNp−MCp=1εN

- Again, each firm’s market power is limited by the price elasticity of demand (ε)(ε)

- A monopolist, (N=1)(N=1)

- As NN increases, markups & market power diminish

Free Entry Equilibrium

So far we've assumed no formal barriers to entry, so firms are free to enter and exit

In Cournot equilibrium, how many firms will there be (i.e. what is N)N)?

Free-Entry Equilibrium

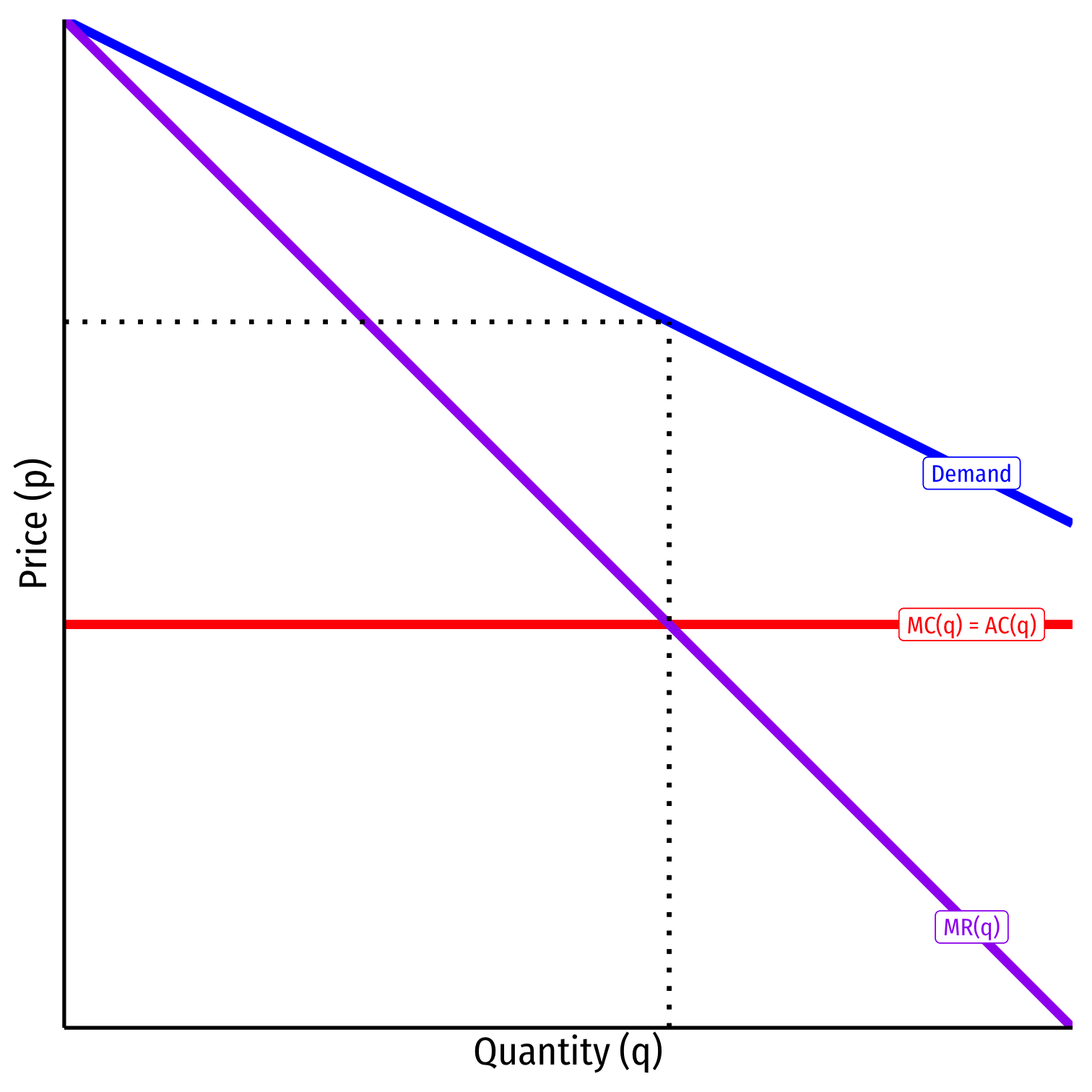

- “Free entry equilibrium”: equilibrium where no additional firms will enter (additional entry must not be profitable); two conditions

- Nash equilibrium in quantities MR(q)=MC(q)MR(q)=MC(q); each firm is profit-maximizing given the number of firms

- Zero-profits: At Cournot output and free-entry number of firms, firms in market earn no profits (no incentive for entry/exit on the margin)

- p=AC(q)p=AC(q)

Free-Entry Equilibrium (Constant Returns to Scale)

Constant returns to scale leads to a problem!

- MC(q)=AC(q)MC(q)=AC(q) are constant and equal

Regardless of number of firms NN, p∗>ACp∗>AC always!

Nothing limits the entry of firms! (Not a satisfactory theory)

- (Aside from a government-imposed barrier to entry), only as N→∞N→∞ do firms stop entering (π=0)(π=0)

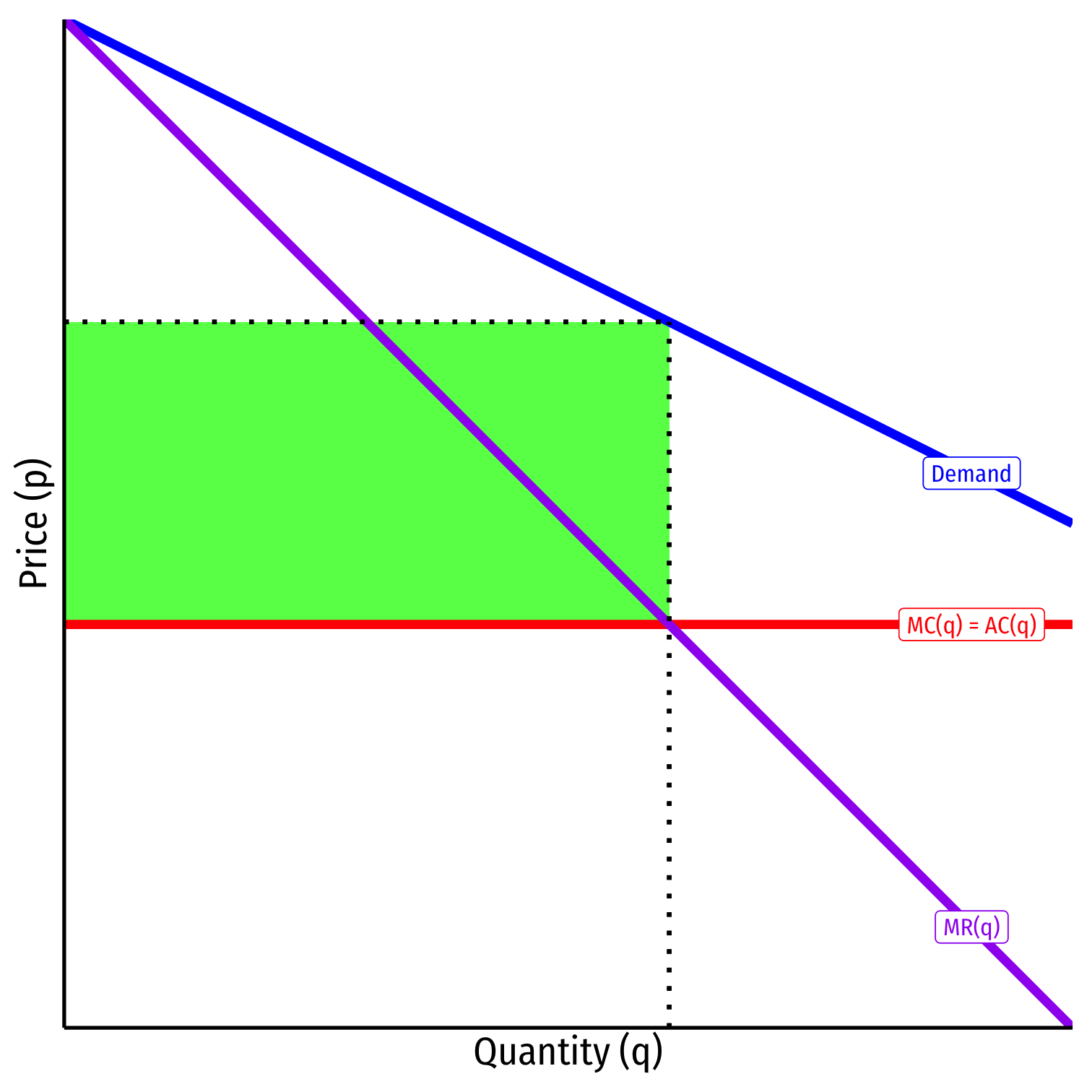

Free-Entry Equilibrium with Economies of Scale

Consider instead a case with economies of scale for each firm ii Ci(qi)=cqi+fCi(qi)=cqi+f

- High fixed costs ff

- constant variable (marginal) costs cc

- AC(q)=c+fqAC(q)=c+fq

Barrier to entry from cost-disadvantage to small-scale entry

Equilibrium where p=AC(q⋆)p=AC(q⋆)

Fixed Costs and Incentives to Enter

Profits with NN firms are again πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)πi=(a−cN+1)2(1b)

- These are gross profits, ignoring the fixed cost of entry ff

Fixed costs don't change any incentives on the margin to produce

- MR=MCMR=MC; ff doesn't affect MCMC

Fixed costs only affect the incentive to enter

- Firms only enter an industry if they expect they can recover ff, so π≥fπ≥f for entry

The Equilibrium Number of Firms

For our Coke & Pepsi example, suppose producing soda comes with a $10.00 fixed cost. How many firms would be in the industry in a free-entry equilibrium?

The Equilibrium Number of Firms

For our Coke & Pepsi example, suppose producing soda comes with a $10.00 fixed cost. How many firms would be in the industry in a free-entry equilibrium?

- Set (gross) profits (ignoring fixed costs) equal to fixed costs

π=f(a−cN+1)2(1b)=f(5−0.5N+1)210.05=10.00N∗=5.36π=f(a−cN+1)2(1b)=f(5−0.5N+1)210.05=10.00N∗=5.36

The Equilibrium Number of Firms

5 firms; a sixth firm could not profitably enter

(If NN is not a whole number, the last whole number is the answer)

In general,

N∗=a−c√bf−1N∗=a−c√bf−1

The Equilibrium Number of Firms

- In our Coke & Pepsi example:

| NN | qiqi | AC(qi)AC(qi) | pp | πiπi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45.00 | 45.00 | $0.72 | $2.75 | $91.25 |

| 2 | 30.00 | 60.00 | $0.83 | $2.00 | $35.00 |

| 3 | 22.50 | 67.50 | $0.94 | $1.625 | $15.31 |

| 4 | 18.00 | 72.00 | $1.06 | $1.40 | $6.20 |

| 5 | 15.00 | 75.00 | $1.17 | $1.25 | $1.25 |

| 6 | 12.86 | 77.14 | $1.28 | $1.14 | -$1.73 |

- A potential sixth firm could not profitably enter (and the 5 other firms would suffer losses)

The Role of Fixed Costs

For our Coke & Pepsi example, suppose producing soda comes with a $75.00 fixed cost. How many firms would be in the industry in a free-entry equilibrium?

The Role of Fixed Costs

For our Coke & Pepsi example, suppose producing soda comes with a $75.00 fixed cost. How many firms would be in the industry in a free-entry equilibrium?

- Set (gross) profits (ignoring fixed costs) equal to fixed costs

π=f(a−cN+1)2(1b)=f(5−0.5N+1)210.05=75.00N∗=1.32π=f(a−cN+1)2(1b)=f(5−0.5N+1)210.05=75.00N∗=1.32

The Equilibrium Number of Firms

- In our Coke & Pepsi example:

| NN | qiqi | AC(qi)AC(qi) | pp | πiπi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45.00 | 45.00 | $2.06 | $2.75 | $31.25 |

| 2 | 30.00 | 60.00 | $2.83 | $2.00 | -$25.00 |

- The Cournot duopoly is the same, but not profitable!

- Second firm does not have incentives to enter; a natural monopoly with 1 firm

Insufficient Entry

With high enough fixed costs, even a single firm (monopolist) would not enter!

Might make sense for government to subsidize a monopolist to break even

- If cost of the subsidy << consumer surplus at monopoly price

Cournot Competition and Market Power

Cournot Equilibrium and Market Power

P−MCP⏟Lerner index=siεP−MCPLerner index=siε

- Lefthand size is Lerner index (market power/markup share of price)

- sisi is the market share of firm ii (qiQ)(qiQ)

- εε is the price elasticity of market demand

Cournot Equilibrium and Market Power: Summary

P−MCP⏟Lerner index=siεP−MCPLerner index=siε

- Cournot duopolists have market power p>MCp>MC

- Market power (left) is inversely related to price elasticity of demand

- Cournot markups will be less than monopoly since si<1si<1

- Endogenous relationship between MCMC and market share sisi

- Firms with lower MCMC will have higher sisi (more efficient firms will have higher market share)

- The greater the number of firms, the less the market power

- as ↑n,↓si↑n,↓si and so ↓P−MCP↓P−MCP

- elasticity of each firm ii's residual demand is εsiεsi

- ↑n↑n raises each firm's εε, reducing its market power

Measuring Market Power and Concentration

P−MCP=siεP−MCP=siε

- If we multiply both sides of the equation by sisi and sum over all NN firms...

Measuring Market Power and Concentration

N∑i=1si(P−MCP)=N∑i=1sisiεN∑i=1si(P−MCP)=N∑i=1sisiε

- If we multiply both sides of the equation by sisi and sum over all NN firms...

Measuring Market Power and Concentration

N∑i=1si(P−MCP)=HHIεN∑i=1si(P−MCP)=HHIε

HHIHHI = Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index (sum of squared market shares); a famous measure of industry concentration (we'll explore later)†

- 0: perfect competition; 1: monopoly

The larger the HHIHHI (holding εε constant), the greater the average weighted markup/industry-wide Lerner index (lefthand side)

Implication: if Cournot model is accurate, measuring the HHIHHI and εε provide good empirical evidence about firm conduct

† In the U.S., HHI is often measured using market shares as percentages, making HHI between 0 and 10,000.

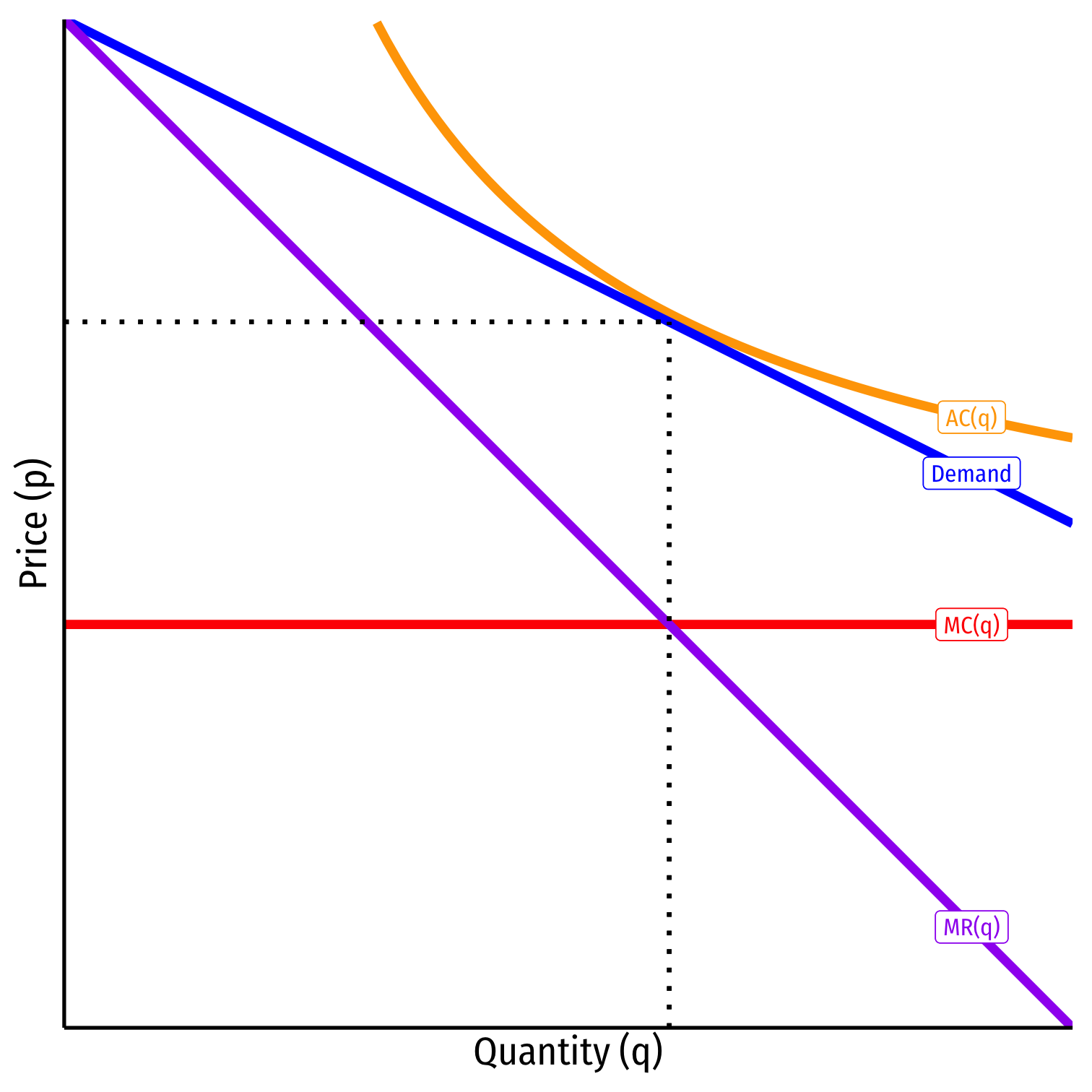

Cournot Oligopoly with Asymmetric Costs

Cournot Oligopoly with Asymmetric Costs Cournot Oligopoly with

Cournot Oligopoly with