2.3 — Bertrand Competition

ECON 326 • Industrial Organization • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/ioS23

ioS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Bertrand Competition: Moblab

Bertrand Competition: Moblab

Each of you selling identical Economics course notes

You will be put into a market with one other player

Each term, both of you simultaneously choose your price

Firm(s) choosing the lowest price get all the customers

Bertrand Competition: Moblab

The lowest price pLpL determines the market demand q=3600−200pLq=3600−200pL

Both firms have $2 cost per unit sold

p=10p=10 maximizes total market profits

Bertrand Competition: Moblab

q=3600−200pLq=3600−200pL

Example:

Suppose Firm 1 sets $p=\$9$ and Firm 2 sets $p=\$10$

Firm 2 sells 0, makes $0

Firm 1 sells $q=3,600-200(\$9)=1,800$ and earns $1,800(\$9-\$2)=\$12,600$ profit

Bertrand Competition

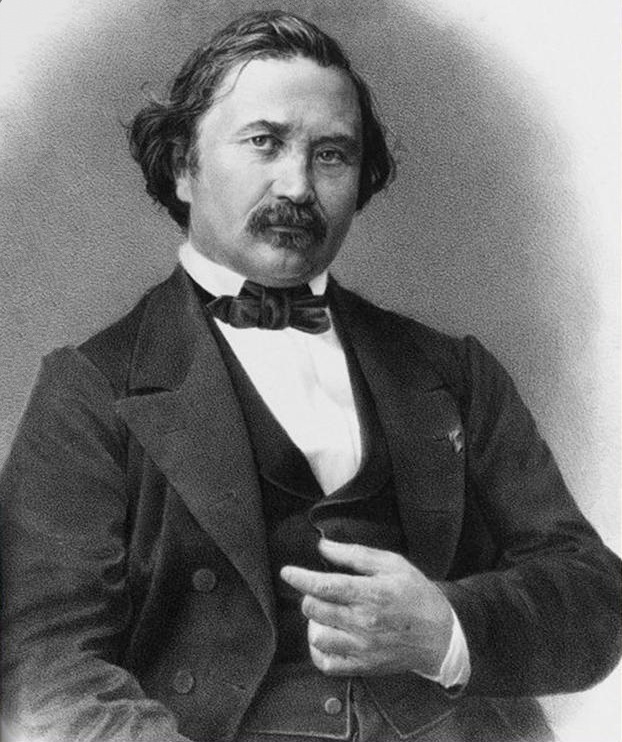

Joseph Bertrand

1822-1890

“Such is the study made in chapter VII of the rivalry between two proprietors, who without having to worry about any competition, manage two springs of identical quality. It would be in their mutual interest to associate [collude] or at least to set a common price so as to make the largest possible revenue from all the buyers, but this solution is rejected. Cournot assumes that one of the proprietors will reduce his prices to attract buyers to him and that the other will, in turn, reduce his prices even more to attract business back to him. They will only stop undercutting each other in this way when either proprietor, even if the other abandoned the struggle, has nothing more to gain from reducing his prices. One major objection to this is that there is no solution under this assumption, in that there is no limit in the downward movement. Indeed, whatever the common price adopted, if one of the proprietors, alone, reduces his price he will, ignoring any minor exceptions, attract all the buyers and thus double his revenue if his rival lets him do so. If Cournot’s formulation conceals this obvious result, it is because he most inadvertently introduces as DD [q1][q1] and D′ [q2] the two proprietors’ respective outputs and by considering them as independent variables he assumes that should either proprietor change his output then the other proprietor’s output could remain constant. It quite obviously could not,” (503).

Bertrand, Joseph, 1883, “Book review of theorie mathematique de la richesse sociale and of recherches sur les principles mathematiques de la theorie des richesses”, Journal de Savants 67: 499–508

Bertrand Competition

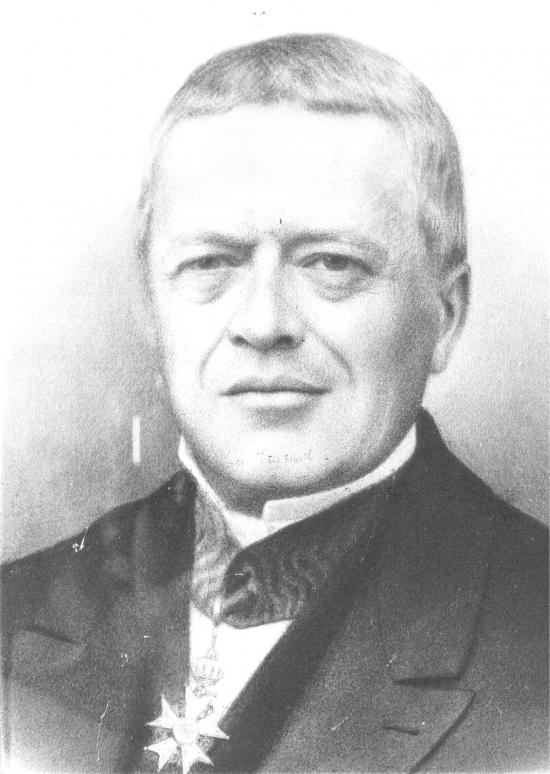

Joseph Bertrand

1822-1890

"Bertrand competition": two (or more) firms compete on price to sell identical goods

Firms set their prices simultaneously

Consumers are indifferent between the brands and always buy from the seller with the lowest price

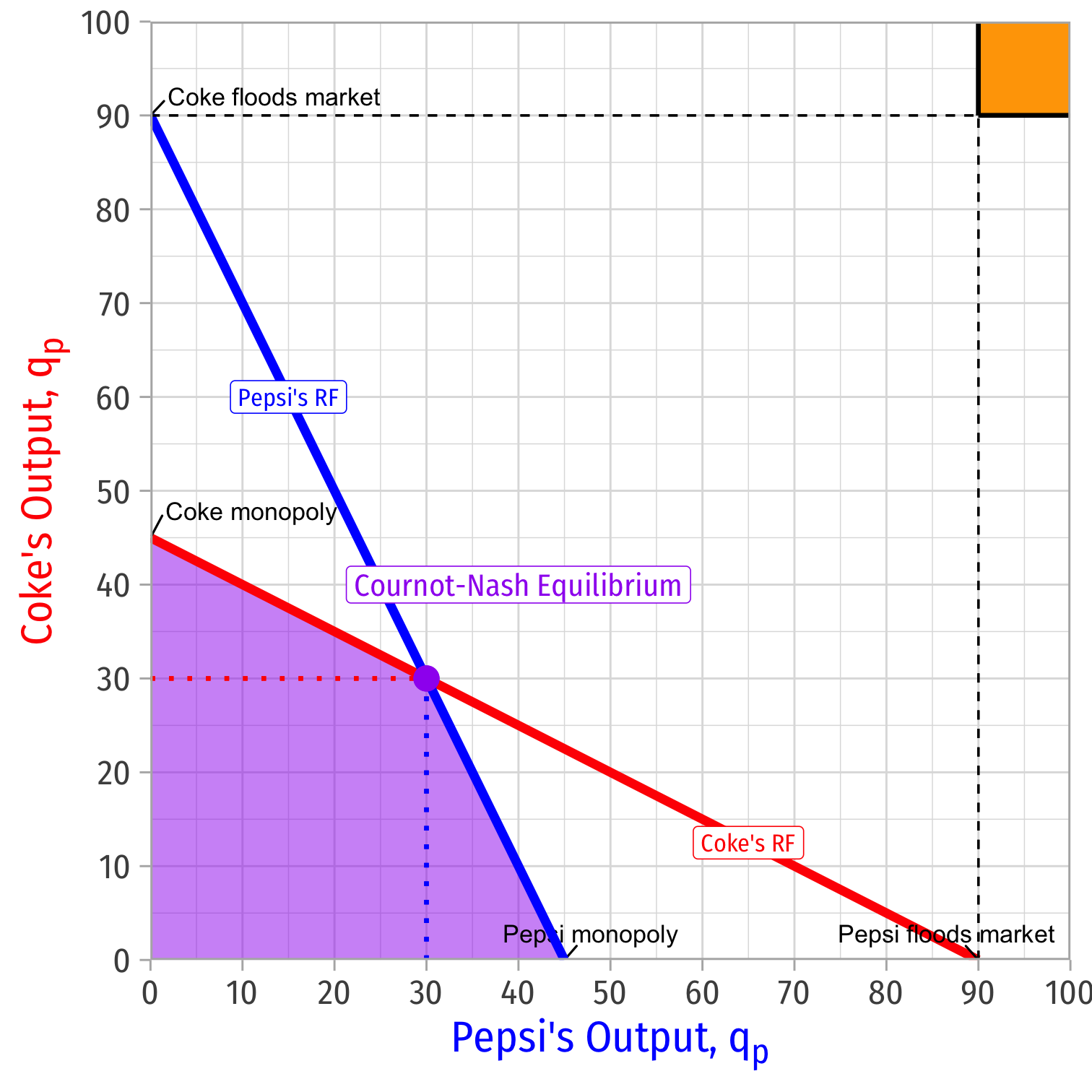

Bertrand Competition: Example

Consider Coke and Pepsi again, with a constant marginal cost of $0.50

Denote Coke's price as pc and Pepsi's price as pp

Let each firm’s sales Q qc and qp be determined by the price each chose, QD(pc) and QD(pp)

Bertrand Competition: Example

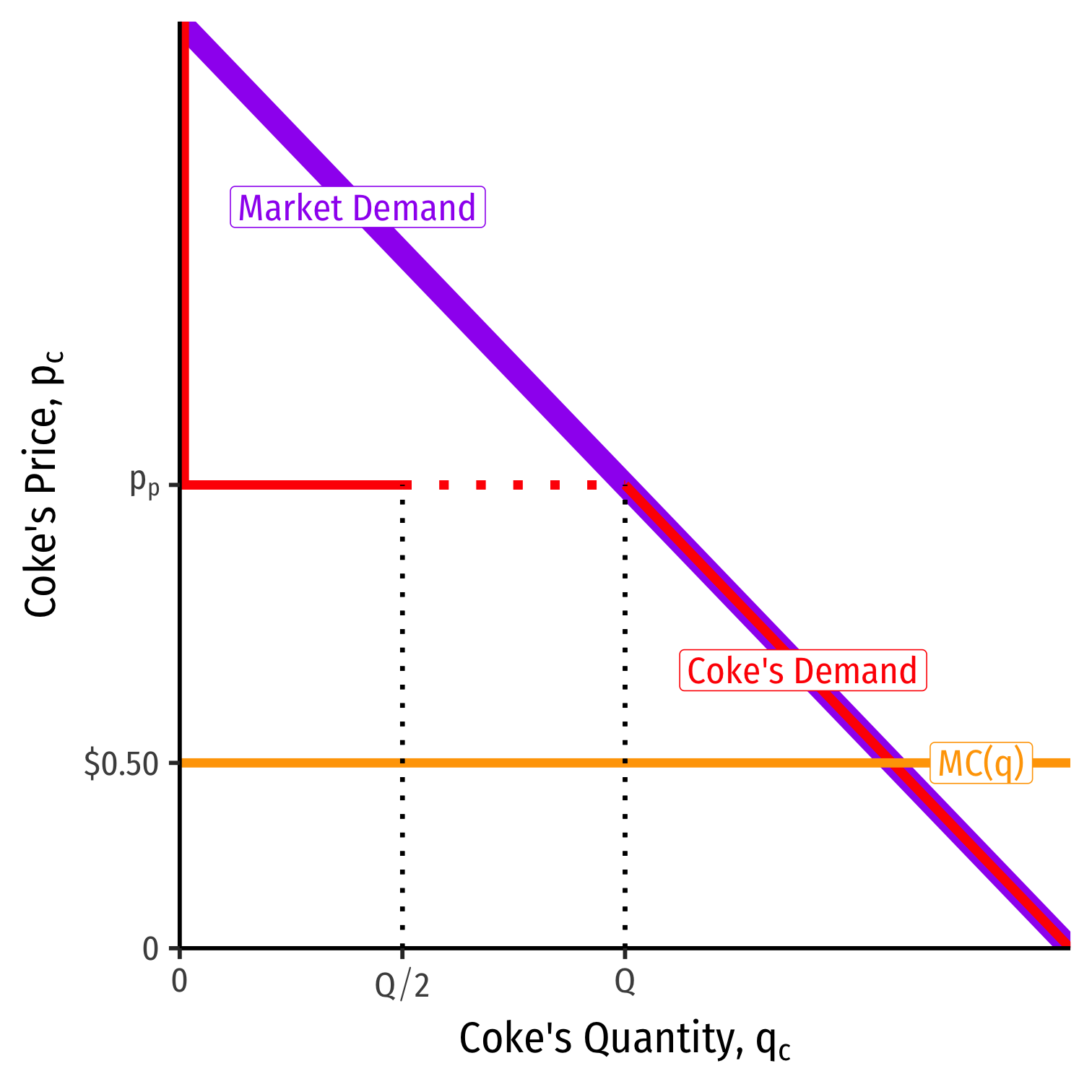

- Demand for soda from Coke:

Bertrand Competition: Example

- Demand for soda from Coke:

- Q if pc < pp

Bertrand Competition: Example

- Demand for soda from Coke:

- Q if pc < pp

- Q2 if pc = pp

Bertrand Competition: Example

- Demand for soda from Coke:

- Q if pc < pp

- Q2 if pc = pp

- 0 if pc > pp

Bertrand Competition: Example

- Demand for soda from Coke:

- Q if pc < pp

- Q2 if pc = pp

- 0 if pc > pp

Bertrand Competition: Example

- Demand for soda from Coke:

- Q if pc < pp

- Q2 if pc = pp

- 0 if pc > pp

- Demand for soda from Pepsi:

- 0 if pc < pp

- Q2 if pc = pp

- Q if pc > pp

Bertrand Competition: Example

- The only way to sell any soda is to match or beat your competitor's price

Bertrand Competition: Example

The only way to sell any soda is to match or beat your competitor's price

Suppose you are Coke

For a given pp, setting your price pc=pp−ϵ for any arbitrary ϵ>0 captures you the entire market Q

Same for Pepsi for pc

Bertrand Competition: Example

Won't charge p<MC, earn losses

Firms continue undercutting one another until pc = pp =MC

- No incentive for either firm to raise or lower price, given other firm‘s price

Nash Equilibrium: (pc=MC,pp=MC)

- Firms earn no profits!

Bertrand Paradox

- Bertrand Paradox: when firms compete on price, the perfectly competitive outcome can be achieved with just 2 firms!

- p=MC

- Q=Q(p=MC)

- π=0

- L=p−MCp=0!

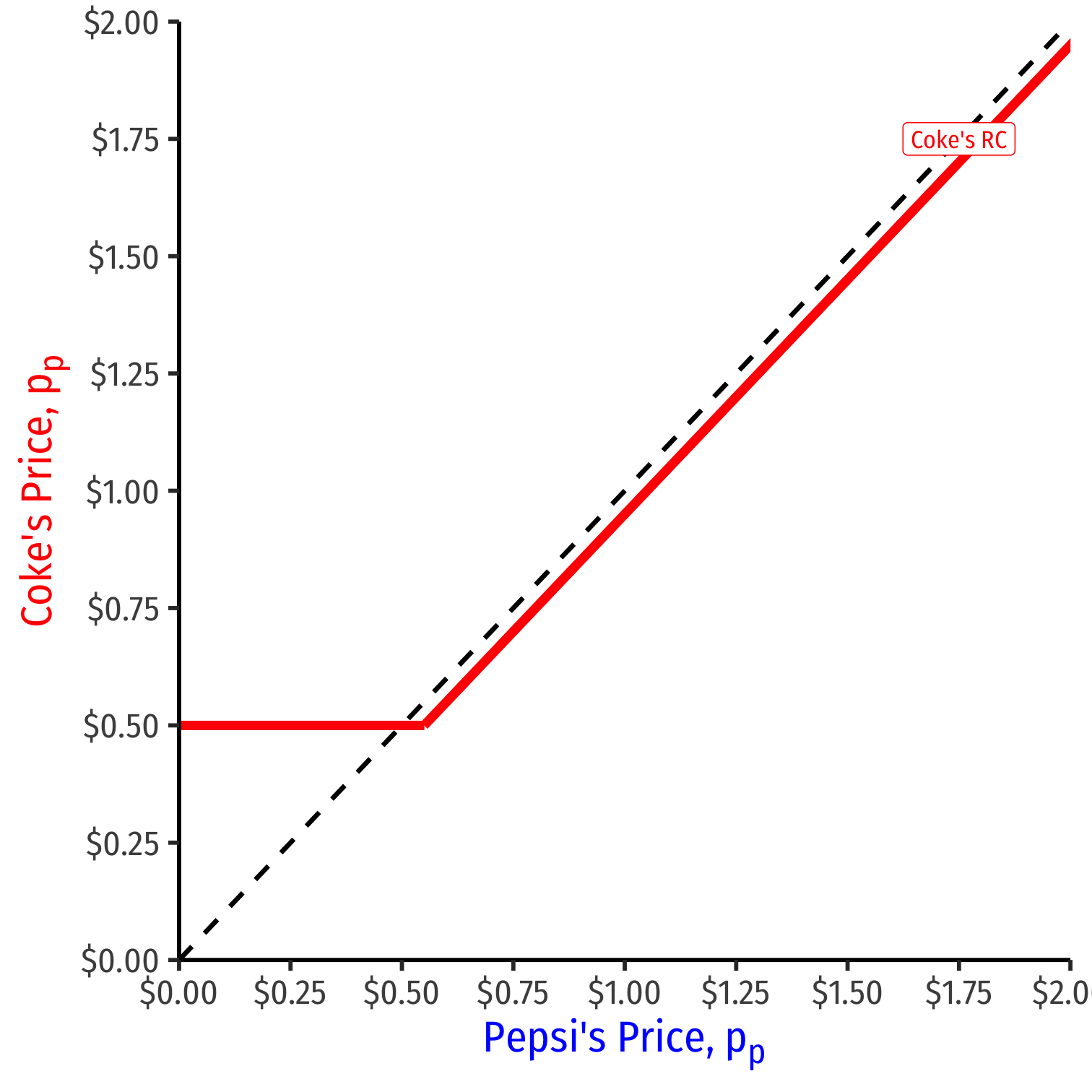

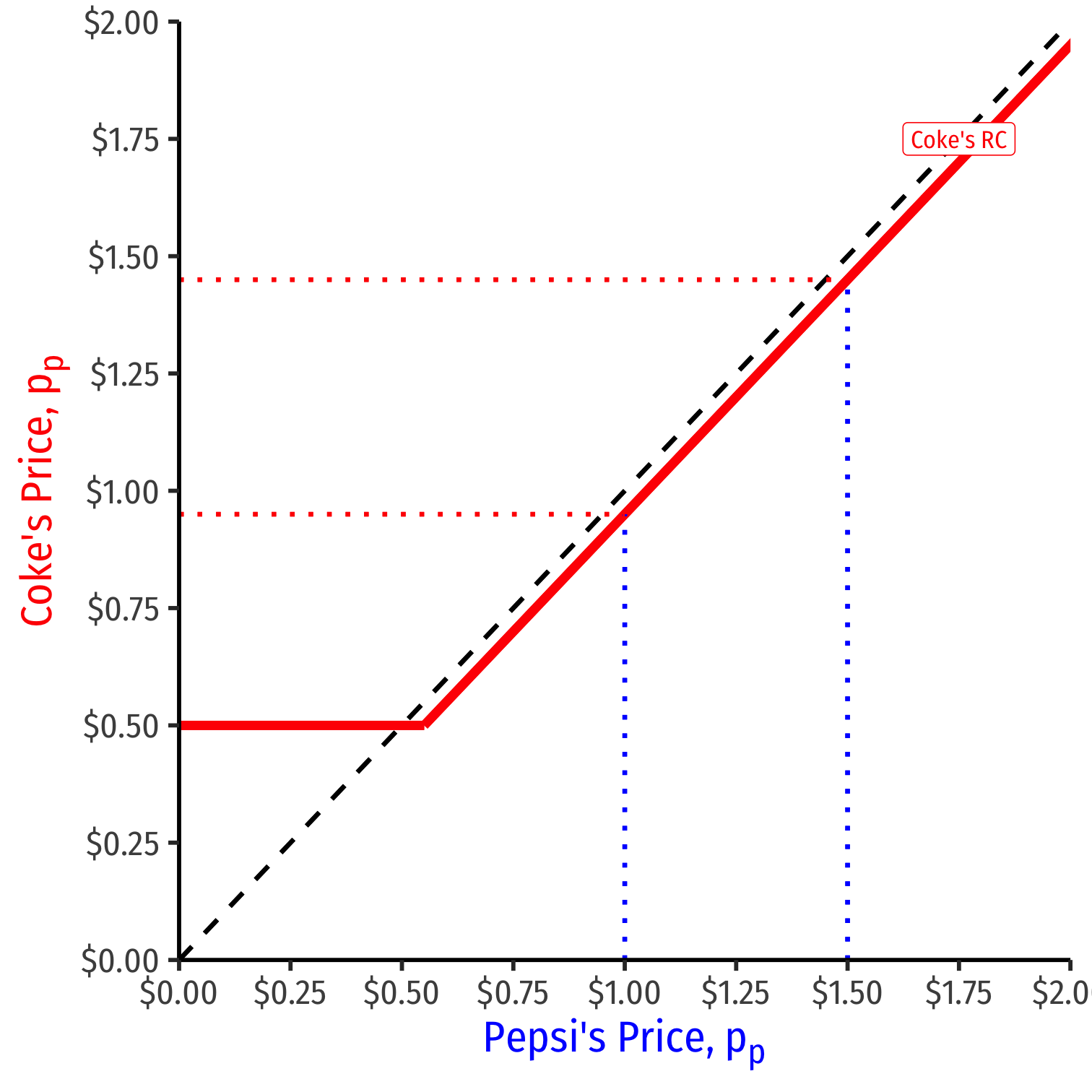

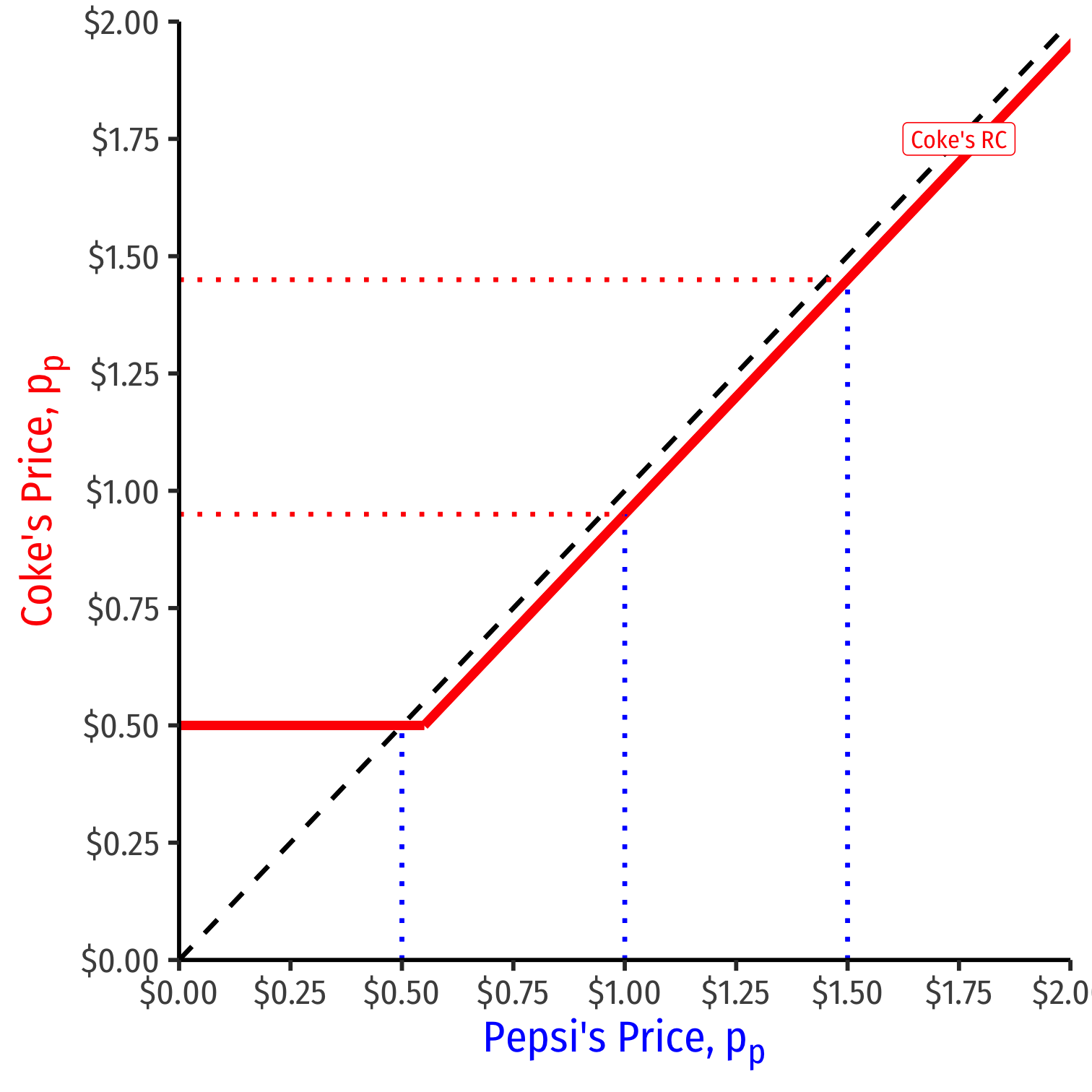

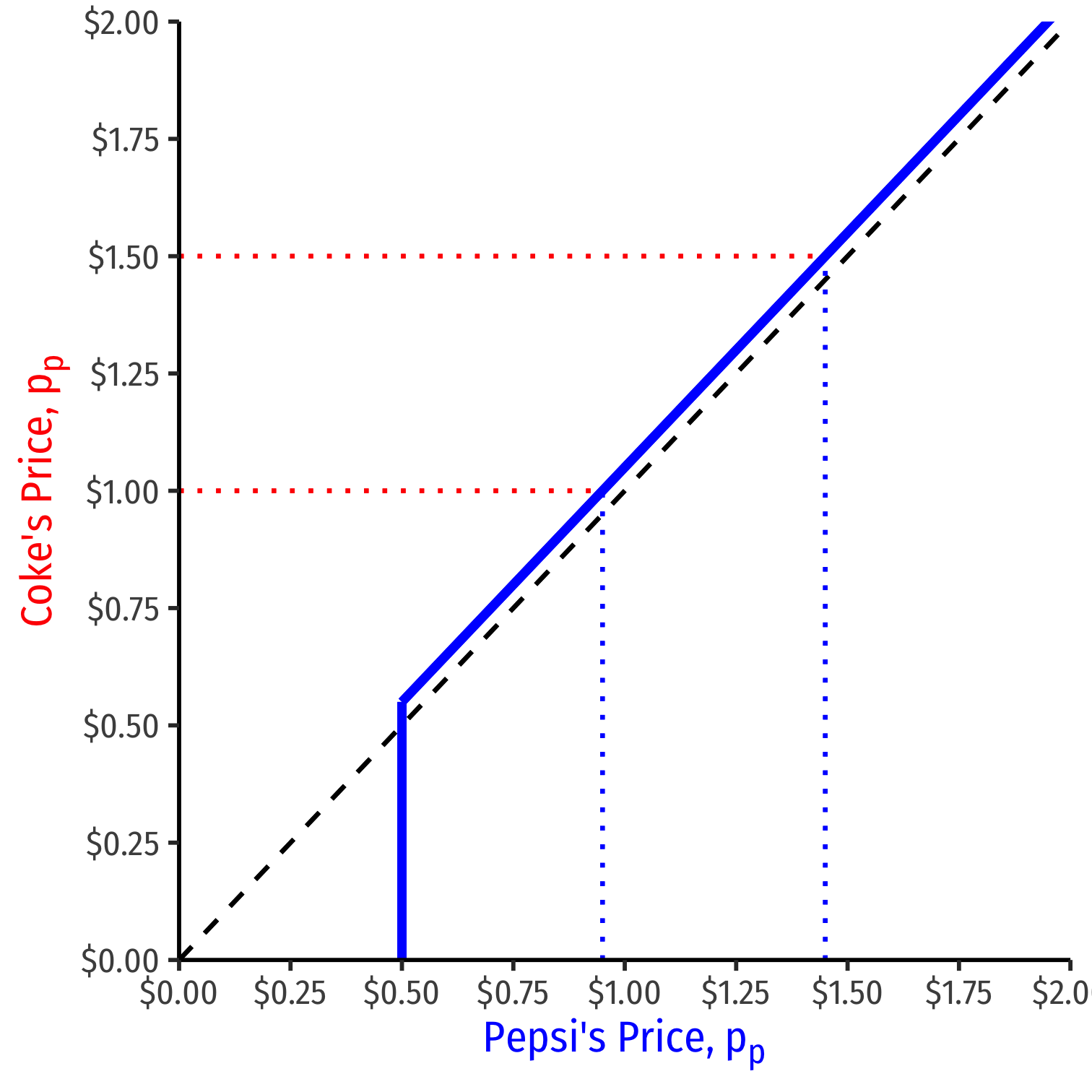

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's price

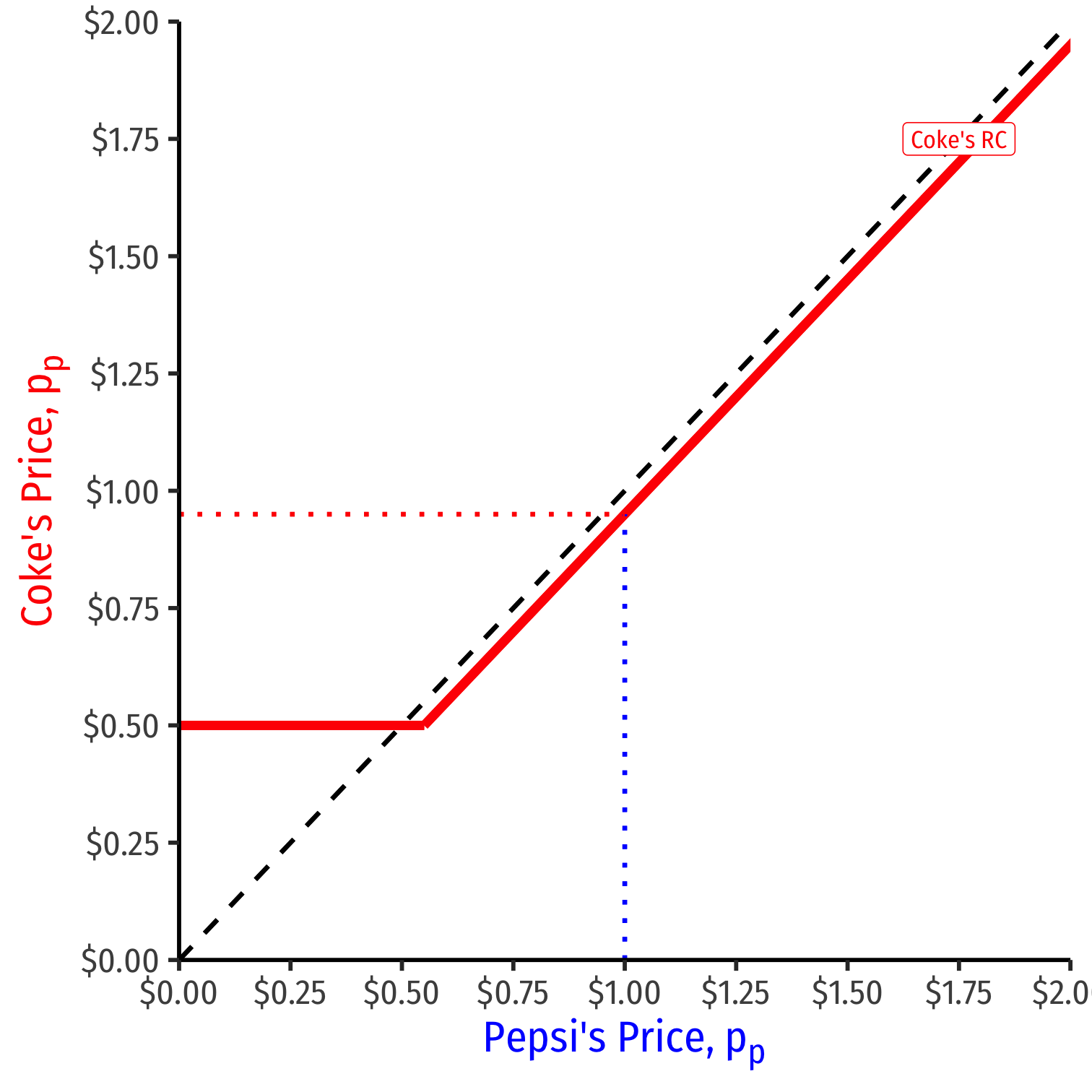

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's price

pc={pp−ϵif pp>cppif pp=c

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $1.00, Coke's best response is $1.00−ϵ

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's price pc={pp−ϵif pp>cppif pp=c

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $1.50, Coke's best response is $1.50−ϵ

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $1.50, Coke's best response is $1.50−ϵ

Coke's Reaction Curve

We can graph Coke's reaction curve to Pepsi's price pc={pp−ϵif pp>cppif pp=c

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $1.50, Coke's best response is $1.50−ϵ

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $1.50, Coke's best response is $1.50−ϵ

- e.g. if Pepsi sets a price of $0.50, (MC) Coke's best response is $0.50 (MC)

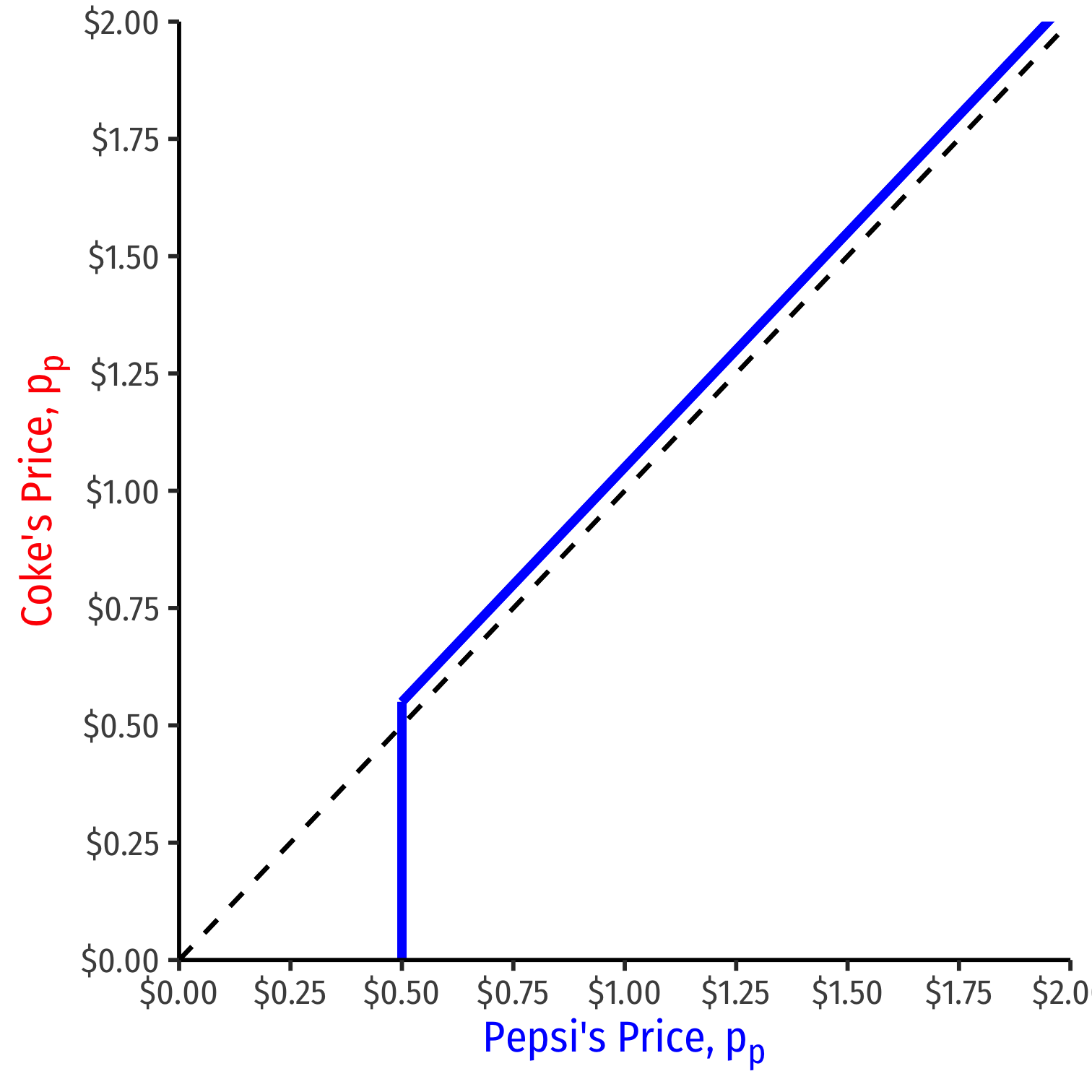

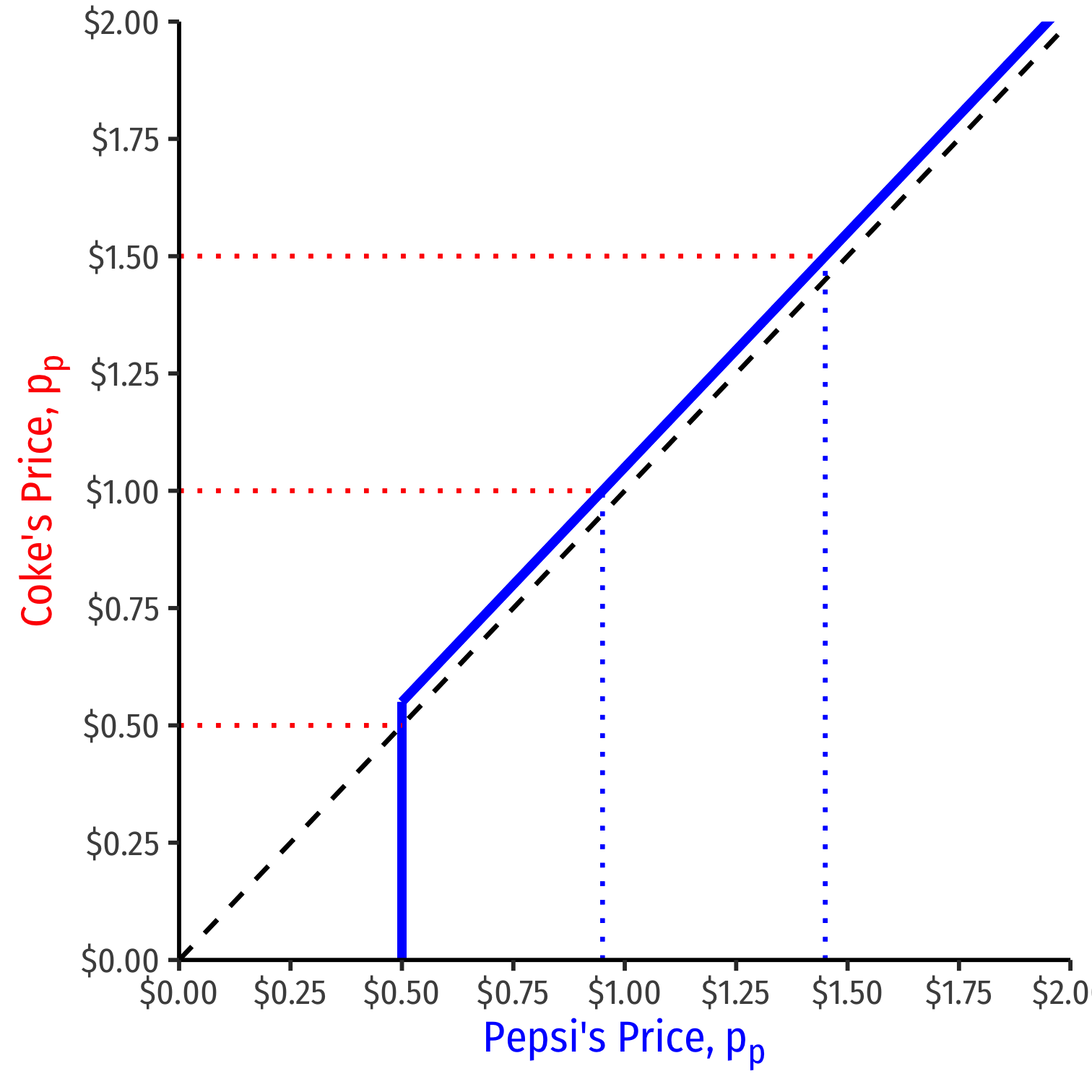

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's price

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's price pp={pc−ϵif pc>cpxif pc=c

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $1.00, Pepsi's best response is $1.00−ϵ

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's price pp={pc−ϵif pc>cpxif pc=c

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $1.00, Pepsi's best response is $1.00−ϵ

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $1.50, Pepsi's best response is $1.50−ϵ

Pepsi's Reaction Curve

We can graph Pepsi's reaction curve to Coke's price pp={pc−ϵif pc>cpxif pc=c

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $1.00, Pepsi's best response is $1.00−ϵ

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $1.50, Pepsi's best response is $1.50−ϵ

- e.g. if Coke sets a price of $0.50 (MC), Pepsi's best response is $0.50 (MC)

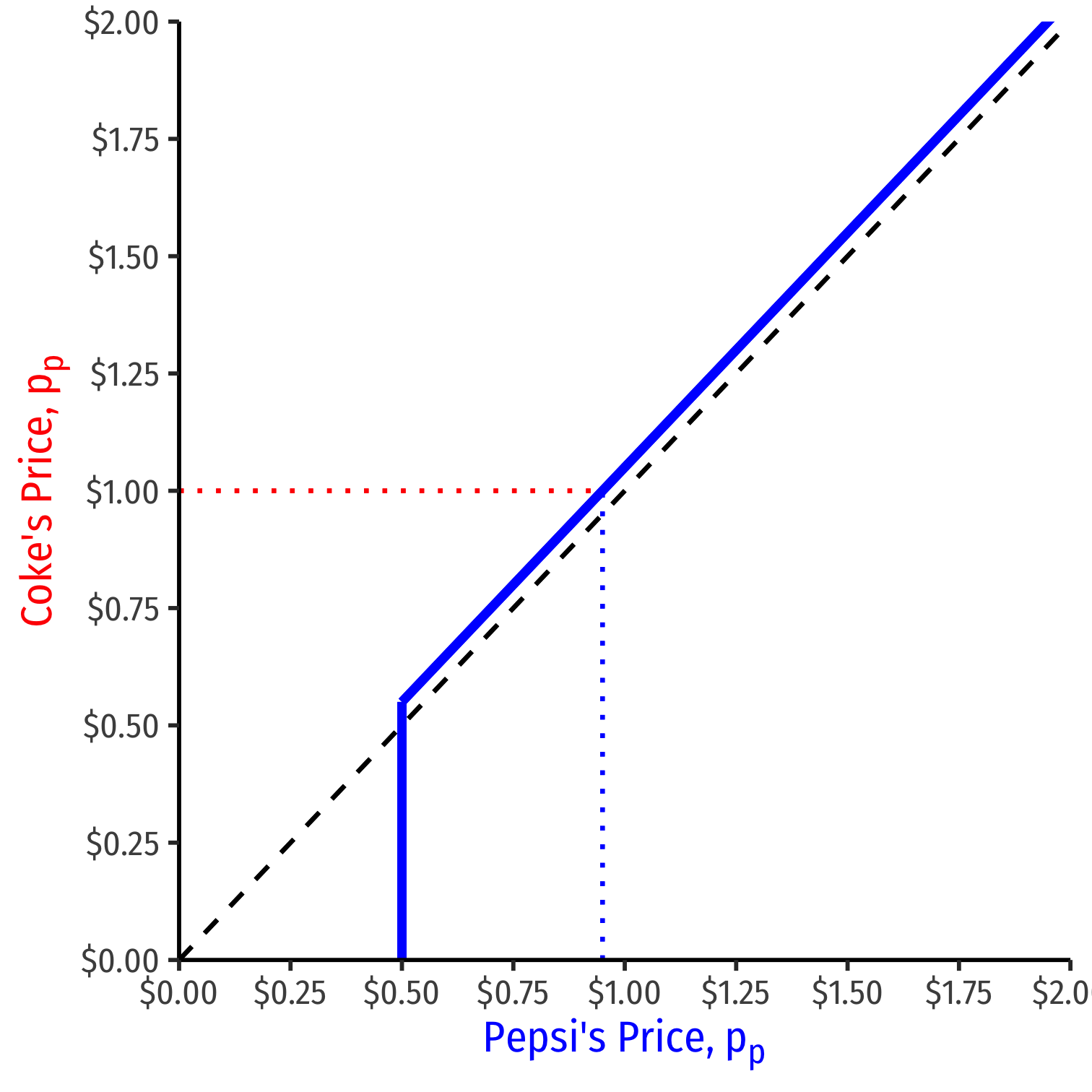

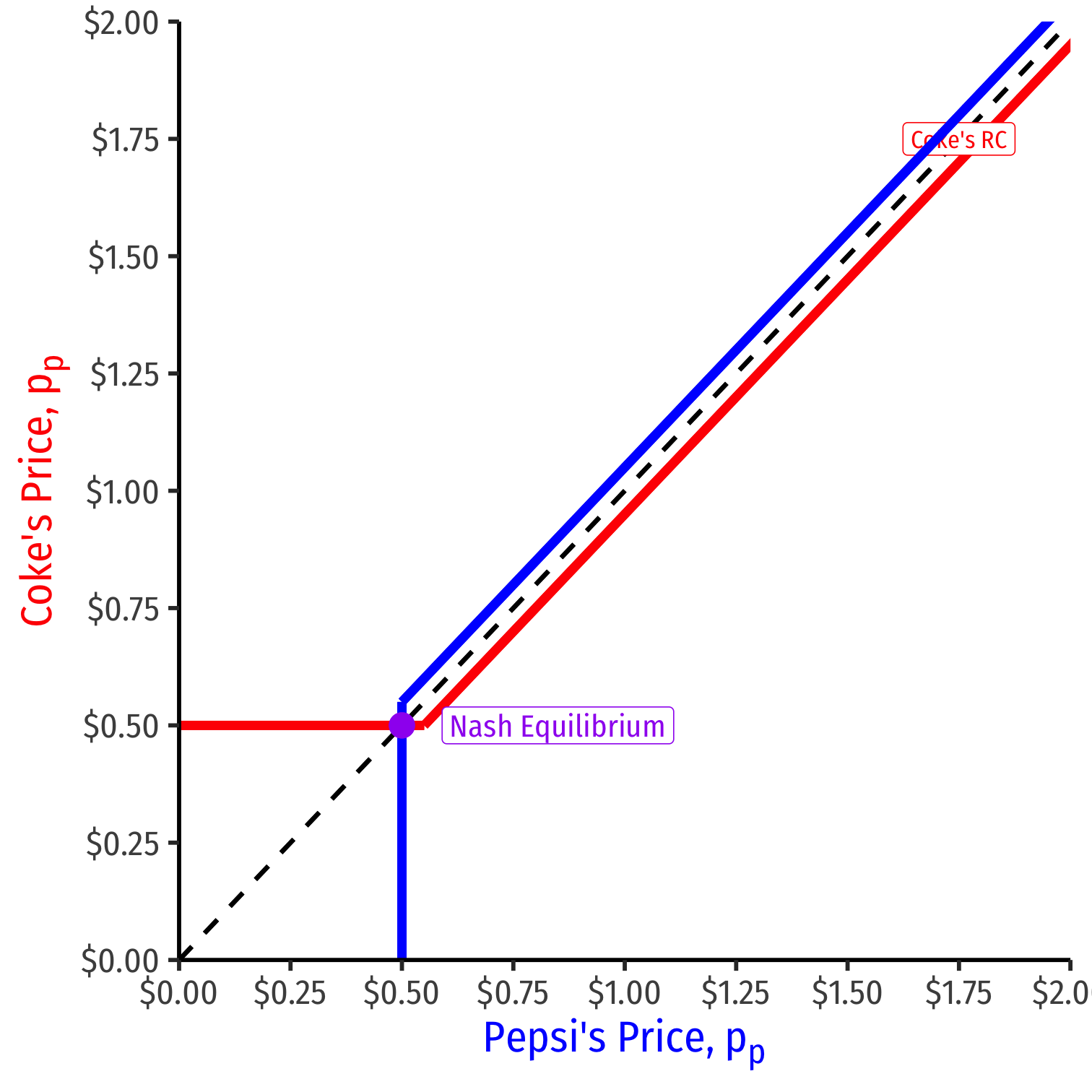

Nash Equilibrium with Reaction Curves

Combine both curves on the same graph

Nash Equilibrium: (pc=MC,pp=MC)

- Where both reaction curves intersect

No longer an incentive to undercut or change price

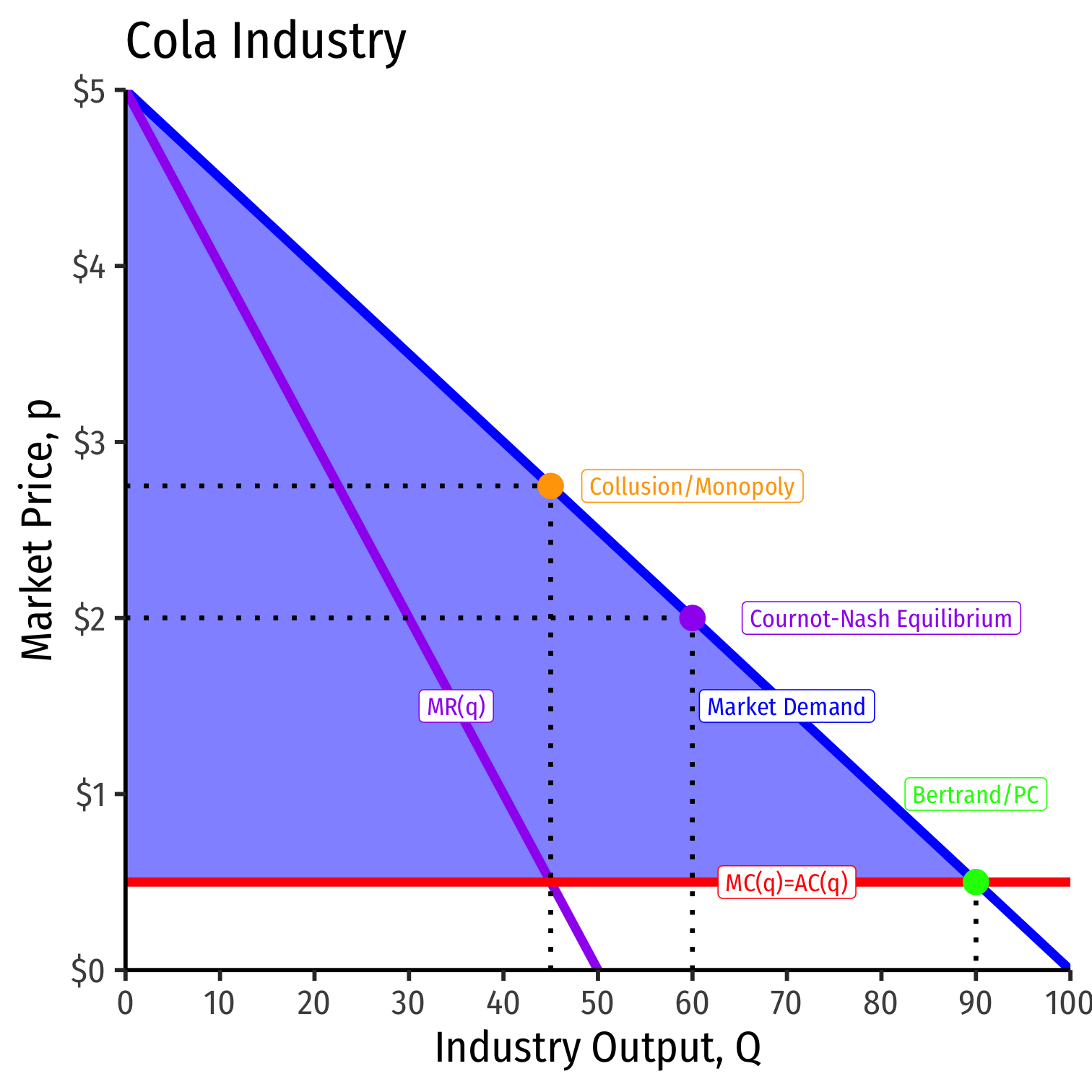

Bertrand Competition: The Market

We can find the industry price & quantity of output (and profits), like in the Cournot model

Here, set p=MC

Bertrand Competition: The Market

We can find the industry price & quantity of output (and profits), like in the Cournot model

Here, set p=MC

5−0.05Q=0.50

Bertrand Competition: The Market

We can find the industry price & quantity of output (and profits), like in the Cournot model

Here, set p=MC

5−0.05Q=0.50

Q∗=90

q⋆1=q⋆2=45

Bertrand Competition: The Market

We can find the industry price & quantity of output (and profits), like in the Cournot model

Here, set p=MC

5−0.05Q=0.50

Q∗=90

q⋆1=q⋆2=45 P∗=c=$0.50

Bertrand Competition: The Market

We can find the industry price & quantity of output (and profits), like in the Cournot model

Here, set p=MC

5−0.05Q=0.50

Q∗=90

q⋆1=q⋆2=45 P∗=c=$0.50

π1=π2=Π=0

Bertrand Competition: The Market

Cournot vs. Bertrand Competition

| Competition | qi | Q | p | πi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collusion | 22.5 | 45.0 | $2.75 | $50.63 |

| Cournot | 30.0 | 60.0 | $2.00 | $45.00 |

| Bertrand | 45.0 | 90.0 | $0.50 | $0.00 |

- Output: Qm<Qc<Qb

- Market price: Pb=c<Pc<Pm

- Profit: πb=0<πc<πm

Where subscripts m is monopoly (collusion), c is Cournot, b is Bertrand

Resolving the Bertrand Paradox

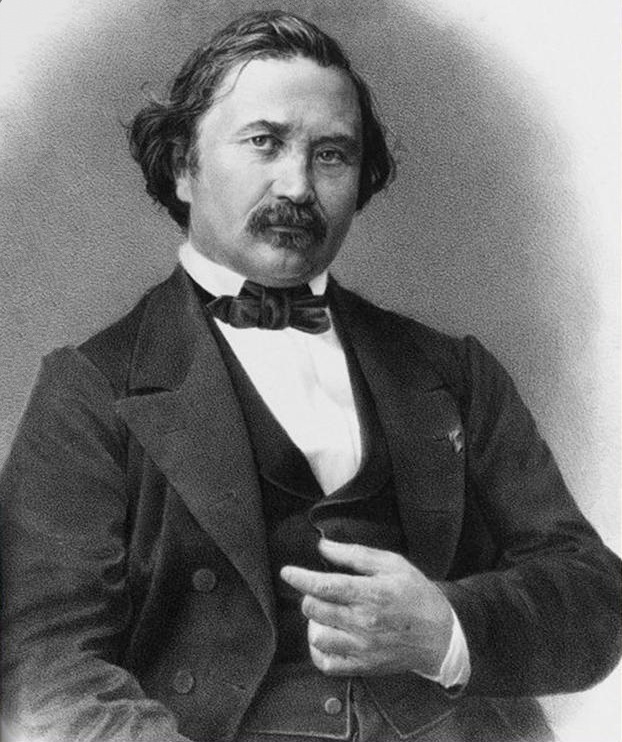

Joseph Bertrand

1822-1890

The paradox happens due to pretty strict assumptions about the model

- No capacity constraints

- Homogeneous goods; consumers only buy from the lower-priced seller

We can extend the Bertrand model in a few ways and see the paradox resolved, we'll examine two:

- Bertrand competition with capacity constraints

- Bertrand competition with differentiated products

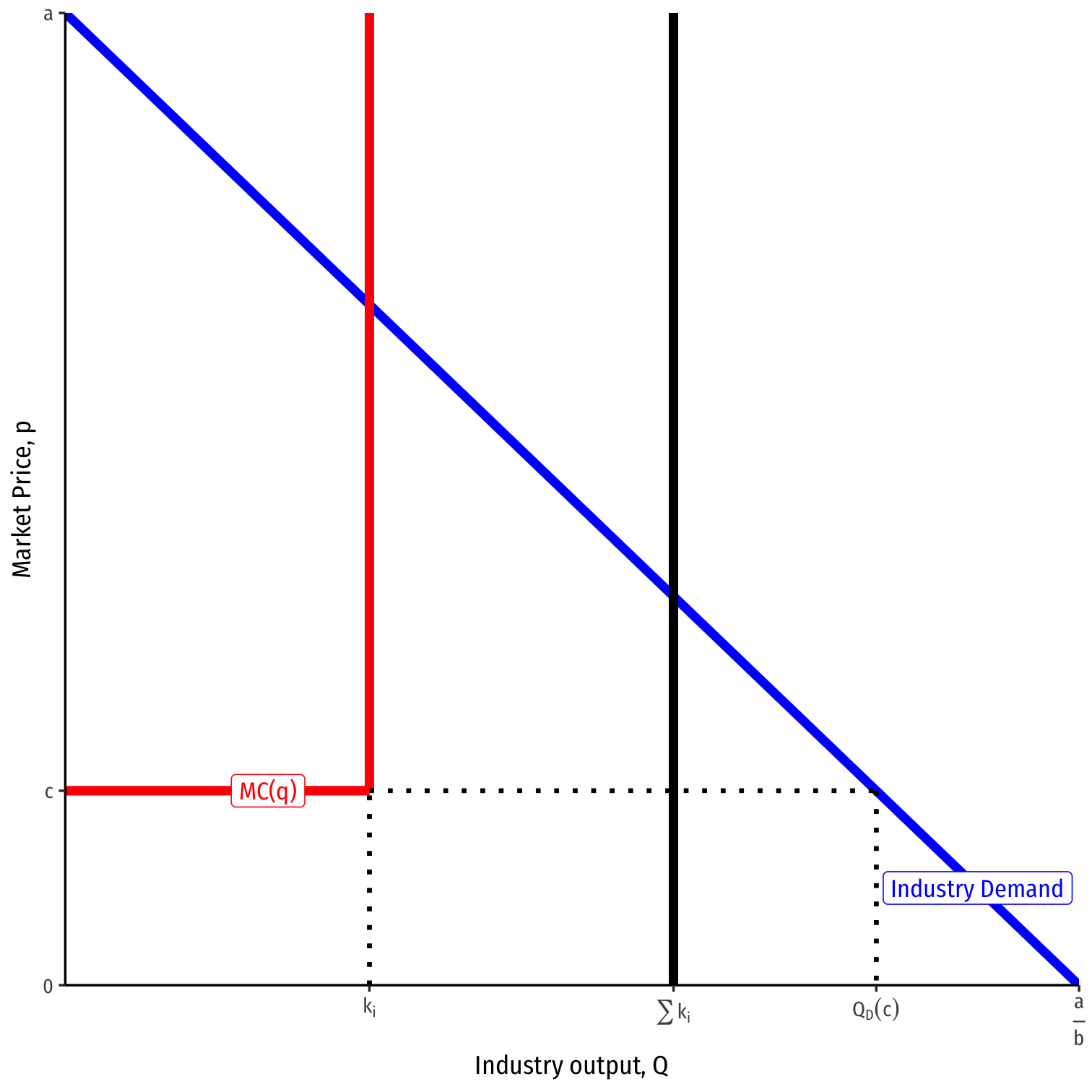

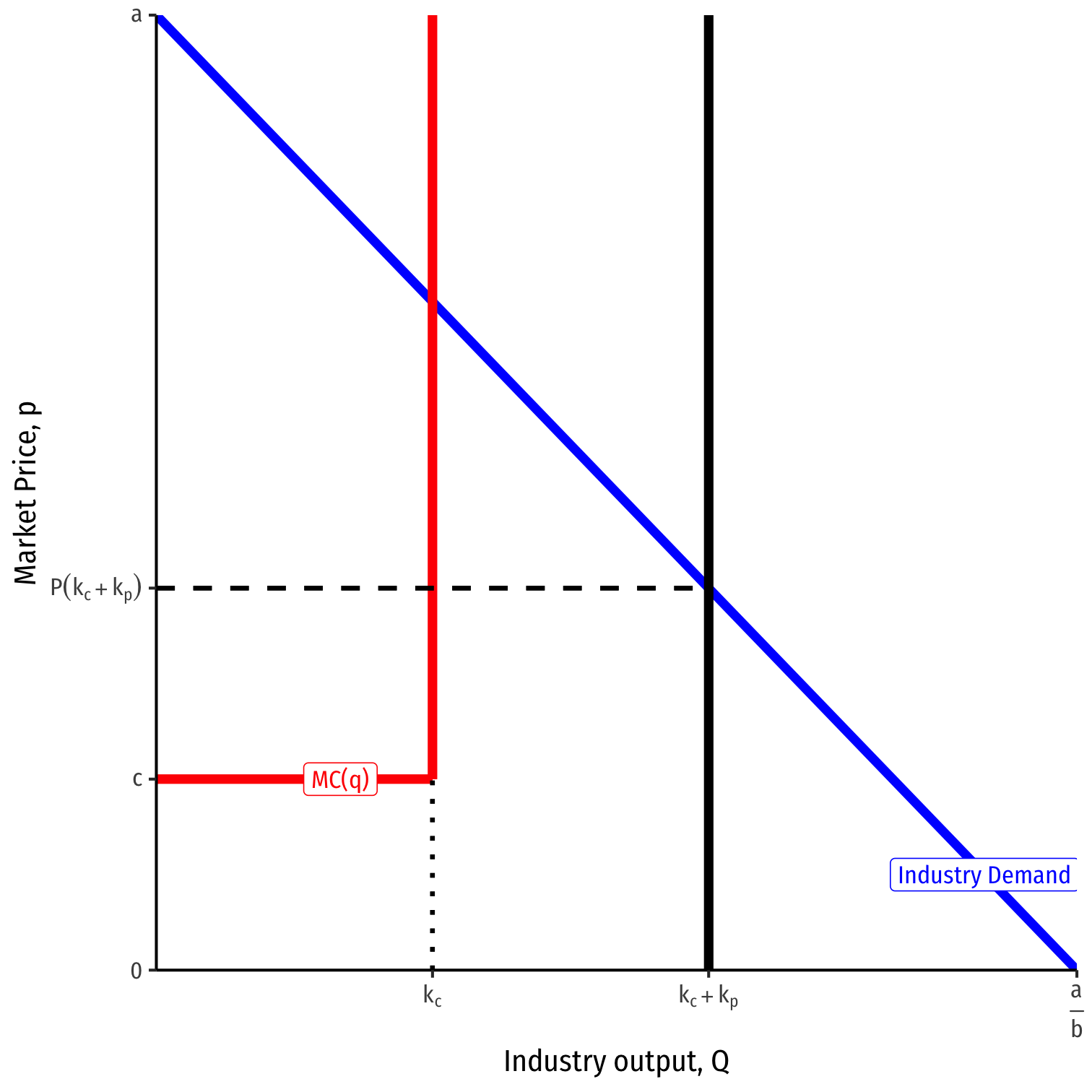

Bertrand Competition with Capacity Constraints

Capacity Constraints

One way to resolve the paradox is to assume that each firm has limited capacity to produce, and cannot supply the entire market

- certainly can't “flood” the market in a price war to drive price to MC

Consider in the short run we assume capital is fixed

Many goods/services are constrained by capacity: hotels, movie theaters, restaurants, etc.

Capacity Constraints

- Suppose each firm can only supply, at most:

q1≤k1q2≤k2k1+k2<QD(c)

Neither firm, nor both of them combined, can supply the entire market at marginal cost

Cost per unit for firm i is c up for qi<ki, then increases rapidly (if not ∞)

Capacity Constraints Change the Game

Suppose Pepsi charges a price pp>c.

Coke would simply have to charge pc=pp−ϵ to capture the market

- But Coke does not have the capacity to serve the whole market!

- Some customers would still buy Pepsi!

- So Pepsi can charge a price above marginal cost

pc=pp=c is not a Nash equilibrium any more

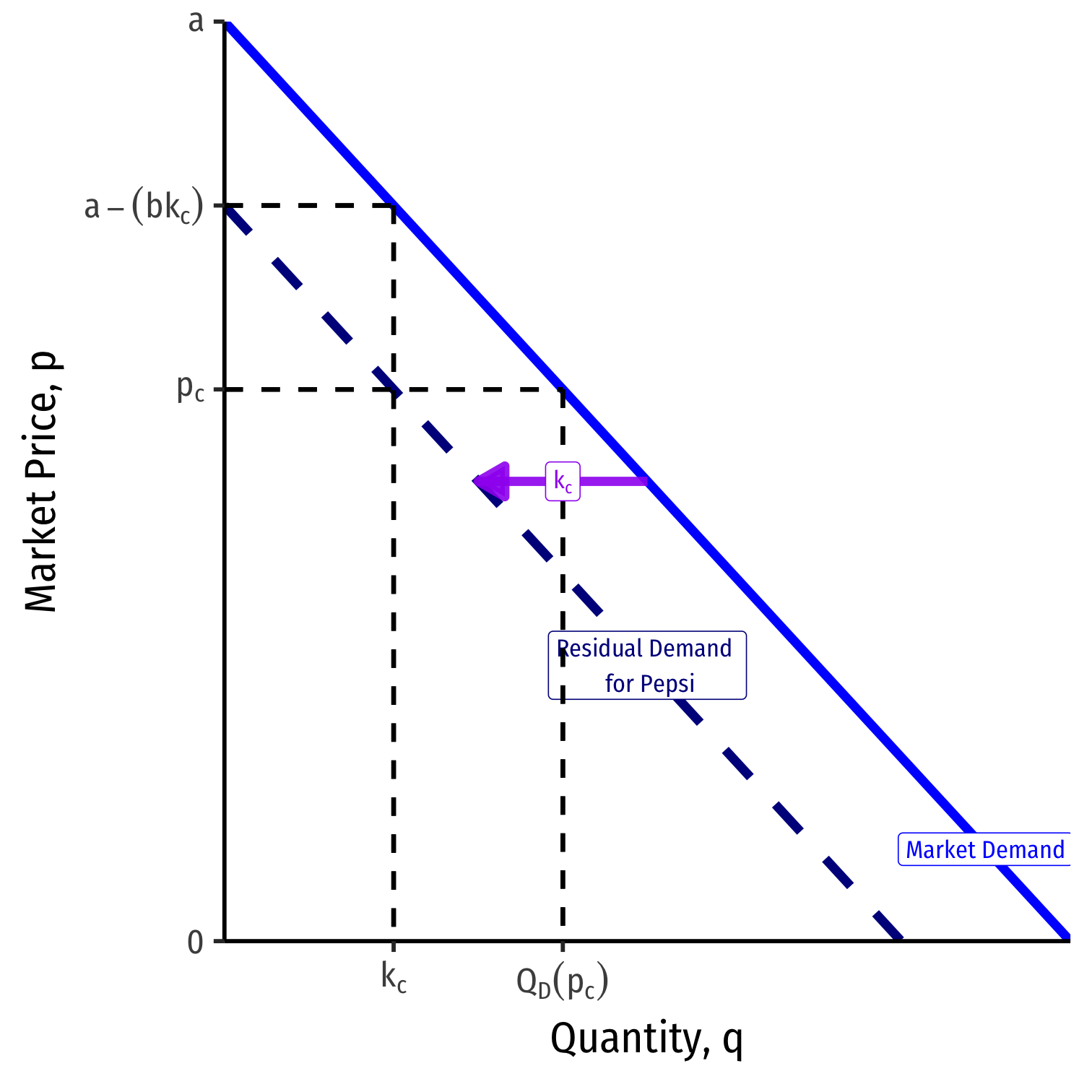

Capacity Constraints

Suppose Coke charges a price lower than Pepsi pc<pp.

- But Coke does not have the capacity to serve the whole market, kc<QD(pc)!

- Some customers will still buy Pepsi!

Since neither firm can serve the whole market, we assume that they ration efficiently, that is, Coke only serve the customers with highest willingness to pay (first)

Pepsi's residual demand is thus subtracting kc from the market demand

- Note: the same as Cournot model residual demand, assuming qc=qk, i.e. Coke sells at capacity

Capacity Constraints

Consider the perspective of Coke:

If it charges pc<pp, then it will sell min{QD(pc),kc}

- Either fulfills entire market demand (if its capacity kc exceeds demand); or its capacity (if kc is less than demand)

- QD is quantity demanded at that price

If it charges pc>pp, then it will sell min{kc,QD(pc)−kp}

- Pepsi sells its full capacity; Coke meets whatever demand is left (either sells its full capacity) or the remaining demand (if less than its capacity)

If pc=pp then we assume demand is allocated according to relative capacities, Coke sells min{kc,kc(kc+kc)D(p)}

- e.g. if Coke has 45% of total industry capacity, it takes 45% of industry demand

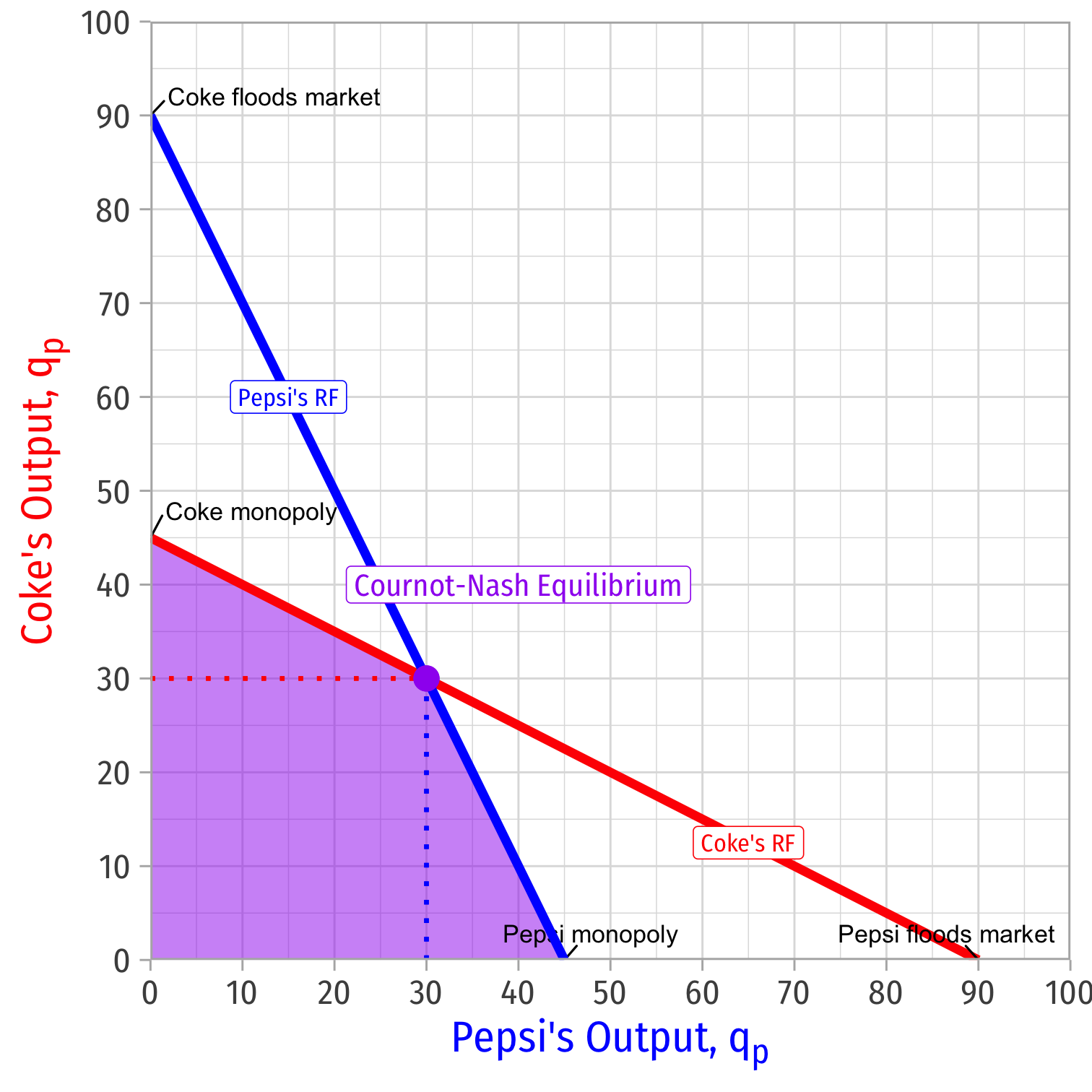

Nash Equilibrium Under Capacity Constraints

- Case 1 (small capacities): Suppose each firm’s capacity is no larger than its Cournot best response to its competitor producing at capacity kc≤30−0.5kpkp≤30−0.5kc

Nash Equilibrium Under Capacity Constraints

Nash equilibrium: pc=pp=P(k1+k2)

- Each firm charges the same price, produces at capacity, and the price is the market demand at their combined capacities

No incentive to lower price, can't produce more output (each at capacity)!

No incentive to raise price either

- Best response to other firm producing at k is your Cournot best response; but not possible (beyond your capacity); raising price makes you worse off (in fact you'd like to sell more and lower your price, but you can't!)

Nash Equilibrium Where Not Capacity Constrained

Case 2 (no capacity constraints): Suppose each firm’s capacity is sufficient to meet the entire market demand at marginal cost pricing

Nash equilibrium: pc=pp=c

Both firms flood the market, charging marginal cost (back to classic Bertrand game)

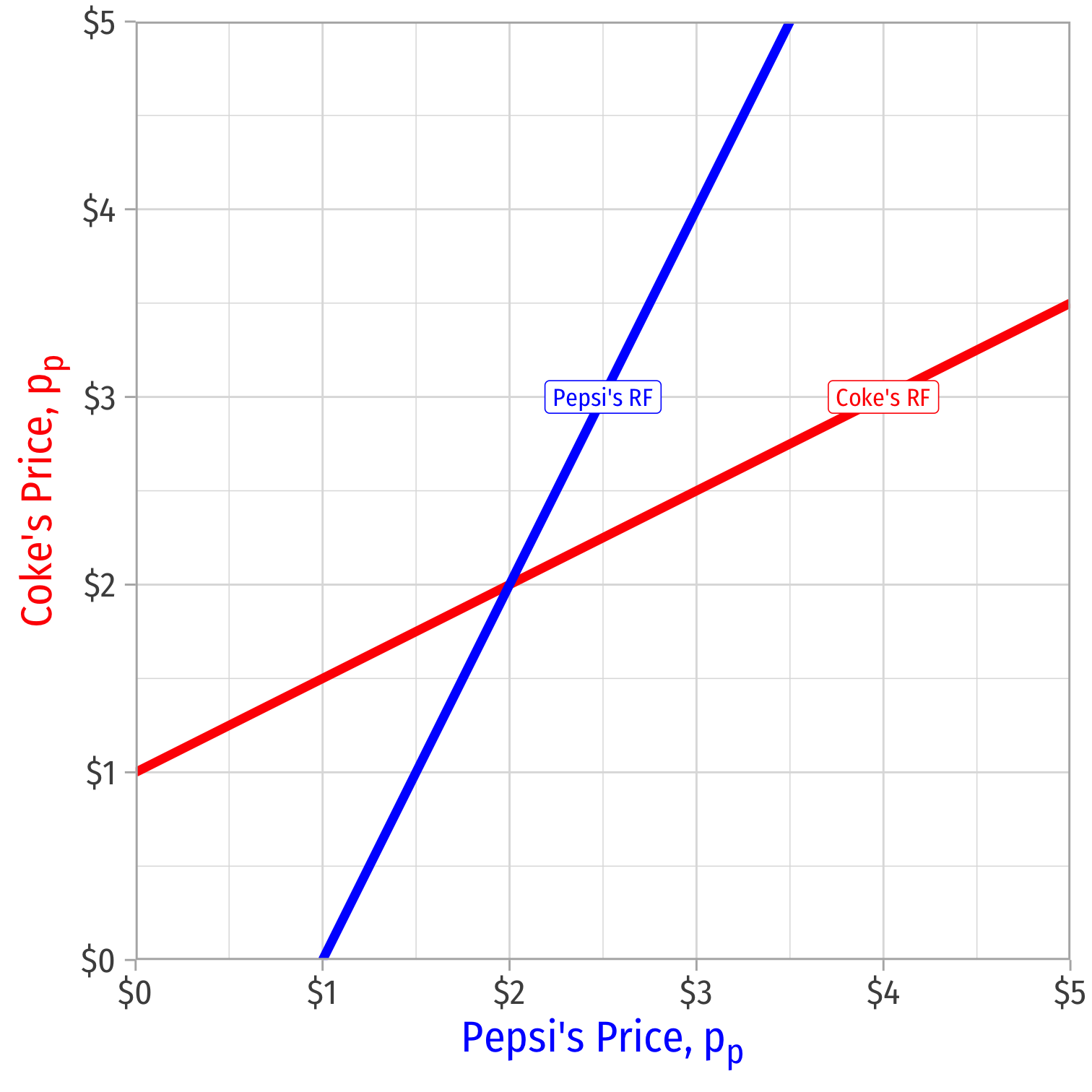

Bertrand Competition with Product Differentiation

Product Differentiation

Now consider instead of homogenous goods, each seller is selling differentiated products (i.e. imperfect substitutes)

- Consumers have preferences between Coke and Pepsi

Same assumptions of Bertrand model:

- Firms set their own prices simultaneously

But now each firm faces its own downward-sloping demand curve

Product Differentiation

Suppose the demand for Coke and for Pepsi, respectively, are: qc=1.00−0.25pc+0.25ppqp=1.00+0.25pc−0.25pp

Notice the positive relationship between pp and qc (and pc and qp): imperfect substitutes

Product Differentiation

Suppose the demand for Coke and for Pepsi, respectively, are: qc=1.00−0.25pc+0.25ppqp=1.00+0.25pc−0.25pp

Notice the positive relationship between pp and qc (and pc and qp): imperfect substitutes

Solving for Coke:

MRc=1.00+0.25pp−0.50pc

Product Differentiation

- Solving for Coke:

MRc=MCc1.00+0.25pp−0.50pc=0.50pc=1.00+0.5pp

- Coke's reaction function to Pepsi's price

Product Differentiation

- Solving for Coke:

MRc=MCc1.00+0.25pp−0.50pc=0.50pc=1.00+0.5pp

Coke's reaction function to Pepsi's price

Eqivalently for Pepsi:

pp=1.00+0.5pc

Reaction Functions and Nash Equilibrium

Reaction Functions and Nash Equilibrium: Algebraically

- Nash Equilibrium algebraically: plug one firm's reaction function into the other's

p∗c=1.00+0.5ppp∗p=1.00+0.5pc

Reaction Functions and Nash Equilibrium: Algebraically

- Nash Equilibrium algebraically: plug one firm's reaction function into the other's

p∗c=1.00+0.5ppp∗p=1.00+0.5pc

p∗p=p∗c=2.00

Conjectural Variations

Cournot vs Bertrand

Outcomes are very different between Cournot and Bertrand competition (with homogeneous products and no capacity constraints)

- Market power & profits with Cournot; decreases with competitors and ε

- Perfect competition with Bertrand

Why? In Bertrand, firm anticipates that if it undercuts rival, can drive its sales to zero; but in Cournot it believes its rival will not change its output

Cournot vs Bertrand

One interpretation: consider a two-stage game between firms with homogeneous products:

- Firms invest in capacity (setting ki)

- Firms compete over price

We can consider this once we learn more game theory

Nash equilibrium: each firm invests in capacity ki=qci, equal to it's Cournot quantity; then prices equal to producing capacity

- Limit capacity to reduce price competition in second stage! (Larger capacity ⟹ more aggressive price cutting)

- In this case, Cournot model is a “shorthand” or reduced form of this 2 stage game

Conjectural Variations

- Cournot's best response function is traditionally called a reaction function - from his discussion about how firms respond to another's output, assuming the other firm does not change its output

Conjectural Variations

Cournot's best response function is traditionally called a reaction function - from his discussion about how firms respond to another's output, assuming the other firm does not change its output

Bowley (1924) calls this a conjecture: firm's belief about how its rivals will react to changes in its output

Conjectural Variations

Cournot's best response function is traditionally called a reaction function - from his discussion about how firms respond to another's output, assuming the other firm does not change its output

Bowley (1924) calls this a conjecture: firm's belief about how its rivals will react to changes in its output

Consider Cournot competition with homogenous goods, identical costs. Firm 1's marginal revenue is:

MR1=P+ΔPΔQΔQΔq1q1

Conjectural Variations

MR1(Q)=P+ΔPΔQΔQΔq1q1

- ΔQΔq1 is the rate of change in industry output that firm 1 expects when it increases its output

- ΔQ=Δq1+Δq2Δq1Δq1

- where Δq2Δq1 is Firm 1’s conjecture about how Firm 2 will respond to Firm 1's output change

Conjectural Variations

MR1(Q)=P+ΔPΔQΔQΔq1q1

ΔQΔq1 is the rate of change in industry output that firm 1 expects when it increases its output

- ΔQ=Δq1+Δq2Δq1Δq1

where Δq2Δq1 is Firm 1’s conjecture about how Firm 2 will respond to Firm 1's output change

Divide everything by Δq1:

ΔQΔq1=1+ν1

- where ν1=Δq2Δq1, Firm 1's conjecture

Conjectural Variations

- Substituting this back in, we get

MR1(Q)=P(Q)+ΔP(Q)ΔQ(1+ν1)q1

- Equilibrium: each firm is profit-maximizing, given its conjecture about its rival

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν1)q1=MC(q1)

And likewise for firm 2

Conjectural Variations

- Substituting this back in, we get

MR1(Q)=P(Q)+ΔP(Q)ΔQ(1+ν1)q1

- Equilibrium: each firm is profit-maximizing, given its conjecture about its rival

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν1)q1=MC(q1)

And likewise for firm 2

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν2)q2=MC(q2)

Conjectural Variations

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν1)q1=MC(q1)

We can characterize effects of different conjectures on equilibrium output

Larger values of ν (more aggressive response by other firm) reduce firm's MR(q) and therefore its output

Conjectural Variations

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν)q1=MC(q1)

- Assume a common conjecture between firms ν=ν1=ν2

Conjectural Variations

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν)q1=MC(q1)

- Assume a common conjecture between firms ν=ν1=ν2

- ν=0: the Cournot conjecture† (reduces to the simple Cournot model)

- rival does not change their output when you increase yours

† Recall the definition of MR(q)=p+ΔpΔqq; or double the slope as demand.

Conjectural Variations

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν)q1=MC(q1)

- Assume a common conjecture between firms ν=ν1=ν2

- ν=0: the Cournot conjecture† (reduces to the simple Cournot model)

- rival does not change their output when you increase yours

† Recall the definition of MR(q)=p+ΔpΔqq; or double the slope as demand.

- ν=−1: the Bertrand conjecture; firm is a price-taker, setting p=MC

- rival reduces their output to offset each increase in yours (leaving price unchanged)

Conjectural Variations

P+ΔPΔQ(1+ν)q1=MC(q1)

- Assume a common conjecture between firms ν=ν1=ν2

- ν=1: the Collusive/monopoly conjecture, firm(s) acts like a monopolist over the industry (since 2q1 is the total industry output)

- rival changes their output exactly same as yours (collusive)

- you can affect total industry output but not your market share (it will always remain constant)

- one firm can't increase its profits at the expense of the other (i.e. cheating cartel is counterproductive)

P+ΔPΔQ2q1=MC(q1)

Conjectural Variations: Flaws & Benefits

Logical flaw in the conjectural variations model: assumes firms make decisions simultaneously, not “reacting” to each other in real time!

- We’ll deal with dynamic responses later

But a useful empirical framework to explore market power and competitiveness

- interpret and estimate ν as a conduct parameter to see if industry performing closer to Cournot/Bertrand/Collusion

- in general, the greater ν is, the greater market power and markups are