4.3 — Asset Specificity

ECON 326 • Industrial Organization • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/ioS23

ioS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Theory of the Firm & Transaction Costs

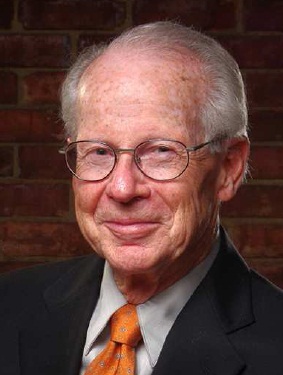

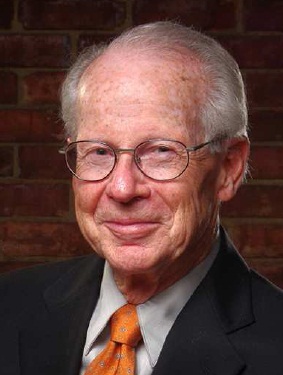

Ronald H. Coase

(1910-2013)

Economics Nobel 1991

- Coase’s (1937) answer to why there are firms is very general, almost tautological, what about the details?

- Life cycle of firms

- Stigler (1951)

- Nexus of Contract Theory

- Alchian and Demsetz (1972); Jensen and Meckling (1976)

- Asset specificity theory

- Williamson (1975); Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978)

- Property Rights View of the Firm

- Grossman and Hart (1986)

Transaction Costs & The Economics of Governance

Transaction Costs and the Economics of Governance

John R. Commons

1862-1945

“[T]he ultimate unit of activity ... must contain in itself the three principles of conflict, mutuality, and order. This unit is a transaction,” (p.4).

Transaction Costs and the Economics of Governance

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“As the term suggests, transaction cost economics adopts a microanalytic approach to the study of economic organization. The focus is on transactions and the economizing efforts that attend the organization thereof...With a well-working interface, as with a well-working machine, these transfers occur smoothly. In mechanical systems we look for frictions: Do the gears mesh, are the parts lubricated, is there needless slippage or other loss of energy?” (p.1).

Transaction Costs and the Economics of Governance

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“The economic counterpart of friction is transaction cost: Do the parties to the exchange operate harmoniously, or are there frequent misunderstandings and conflicts that lead to delays, breakdowns, and other malfunctions? Transaction cost analysis supplants the usual preoccupation with technology and steady-state production (or distribution) expenses with an examination of the comparative costs of planning, adapting, and monitoring task completion under alternative governance structures.“ (pp.1-2).

Transaction Costs and the Economics of Governance

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“Rather than characterize the firm as a production function, transaction cost economics maintains that the firm is (for many purposes at least) more usefully regarded as a governance structure.” (p.13)

“Contrary to earlier conceptions–where the economic institutions of capitalism are explained by reference to class interests, technology, and/or monopoly power–the transactions cost approach maintains that these institutions have the main purpose and effect of economizing on transaction costs,” (p.1).

Transaction Costs and the Economics of Governance

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“Governance...is the means by which to infuse order, thereby to mitigate conflict and realize mutual gain...Furthermore, the transaction is made the basic unit of analysis,” (p.2).

The Fundamental Transformation

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

A contract between two parties constitutes a “fundamental transformation” from ex ante competitive market to an ex post bilateral monopoly

- Two parties depend on one another’s performance to jointly capture the gains from exchange (“quasi-rents” of cooperation)

- Committing a factor of production into such a relationship is a specific investment, possibly sunk cost

Creates the possibility of post-contractual opportunism by the parties

The Fundamental Transformation

This bilateral dependency creates “quasi rents” from cooperation that might be appropriated by a party

Need to contract ex ante to protect ex post possibility of someone threatening to appropriate the rents

Inability to prevent this may cause parties to inefficiently avoid making agreements!

Appropriable Quasi-Rents

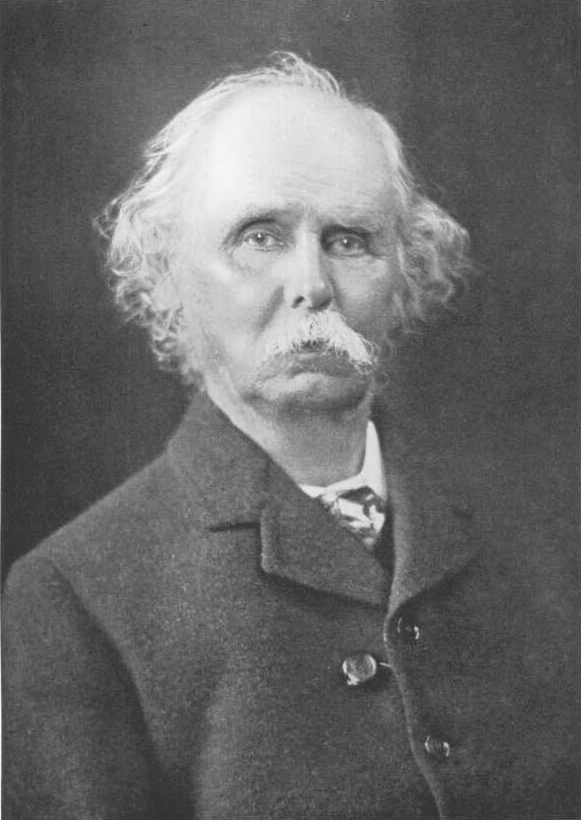

Alfred Marshall

1842-1924

“Indeed, in some cases and for some purposes, nearly the whole income of a business may be regarded as a quasi-rent, that is an income determined for the time by the state of the market for its wares, with but little reference to the cost of preparing for their work the various things and persons engaged in it. In other words it is a composite quasi-rent divisible among the different persons in the business by bargaining, supplemented by custom and by notions of fairness...Thus the head clerk in a business has an acquaintance with men and things, the use of which he could in some cases sell at a high price to rival firms. But in other cases it is of a kind to be of no value save to the business in which he already is; and then his departure would perhaps injure it by several times the value of his salary, while probably he could not get half that salary elsewhere,” (VI.viii.35).

Appropriable Quasi-Rents

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Coase's fundamental insight [was] that transaction, coordination, and contracting costs must be considered explicitly in explaining the extent of vertical integration...[We] explore one particular cost of using the market system-the possibility of postcontractual opportunistic behavior,” (p.297)

“The particular circumstance we emphasize as likely to produce a serious threat of this type of reneging on contracts is the presence of appropriable specialized quasi rents. After a specific investment is made and such quasi rents are created, the possibility of opportunistic behavior is very real. Following Coase's framework, this problem can be solved in two possible ways: vertical integration or contracts,” (p.298)

Appropriable Quasi-Rents

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“An appropriable quasi rent is not a monopoly rent in the usual sense, that is, the increased value of an asset protected from market entry over the value it would have in an open market. [It] can occur with no market closure or restrictions placed on rival assets. Once install, an asset may be so expensive to remove or so specialized to a particular user that if the price paid to the owner was somehow reduced the asset's services to that user would not be reduced,” (p.299).

Appropriable Quasi-Rents

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Because of transaction and mobility costs, ‘market power’ will exist in many situations not commonly called monopolies. There may be many potential suppliers of a particular asset to a particular user but once the investment in the asset is made, the asset may be so specialized to a particular user that monopoly or monopsony power, or both, is created,” (p.299).

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Asset Specificity

Asset Specificity

“Asset specificity”: degree to which an asset has alternative valuable uses outside a specific use

- Or degree to which it loses value for other uses

General assets can easily be diverted to other productive uses for most or all of their value

- Very liquid: easily re-sold on thick markets for most of its value

- e.g. trucks, shipping containers, hammers, computers

Asset Specificity

- Specific assets have few alternative uses outside a specific use

- Illiquid: would sell for drastically lower than its value

- e.g. dyes, drill presses, designed to make a very specific output

Asset Specificity

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“Four types of asset specificity are usefully distinguished:

[1.] site specificity - e.g. successive stations that are located in a cheek-by-jowl relation to each other so as to economize on inventory and transportation expenses;

[2.] physical asset specificity - e.g. specialized dies that are required to produce a component;

[3.] human asset specificity that arises in a learning-by-doing fashion; and

[4.] dedicated assets, which represent a discrete investment in generalized...production capacity that would not be made but for the prospect of selling a significant amount of product to a specific consumer,” (p. 95).

Asset Specificity

Olvier E Williamson

1932-

Economics Nobel 2009

“Transaction cost economics maintains that the principal factor that is responsible for transaction cost differences among transactions is variations in asset specificity. Transactions that are supported by non-specific (redeployable) investments are ones for which neoclassical analysis is well-suited to deal. As a condition of asset specificity becomes more important, however, exchange relations take on a progressively stronger bilateral trading character. The reason is that parties to such trades have a stake in preserving the continuity of the relationship,” (p. 367).

Riordan, Michael H and Oliver E Williamson, 1985, “Asset Specificity and Economic Organization,” International Journal of Industrial Organization 3: 365-378.

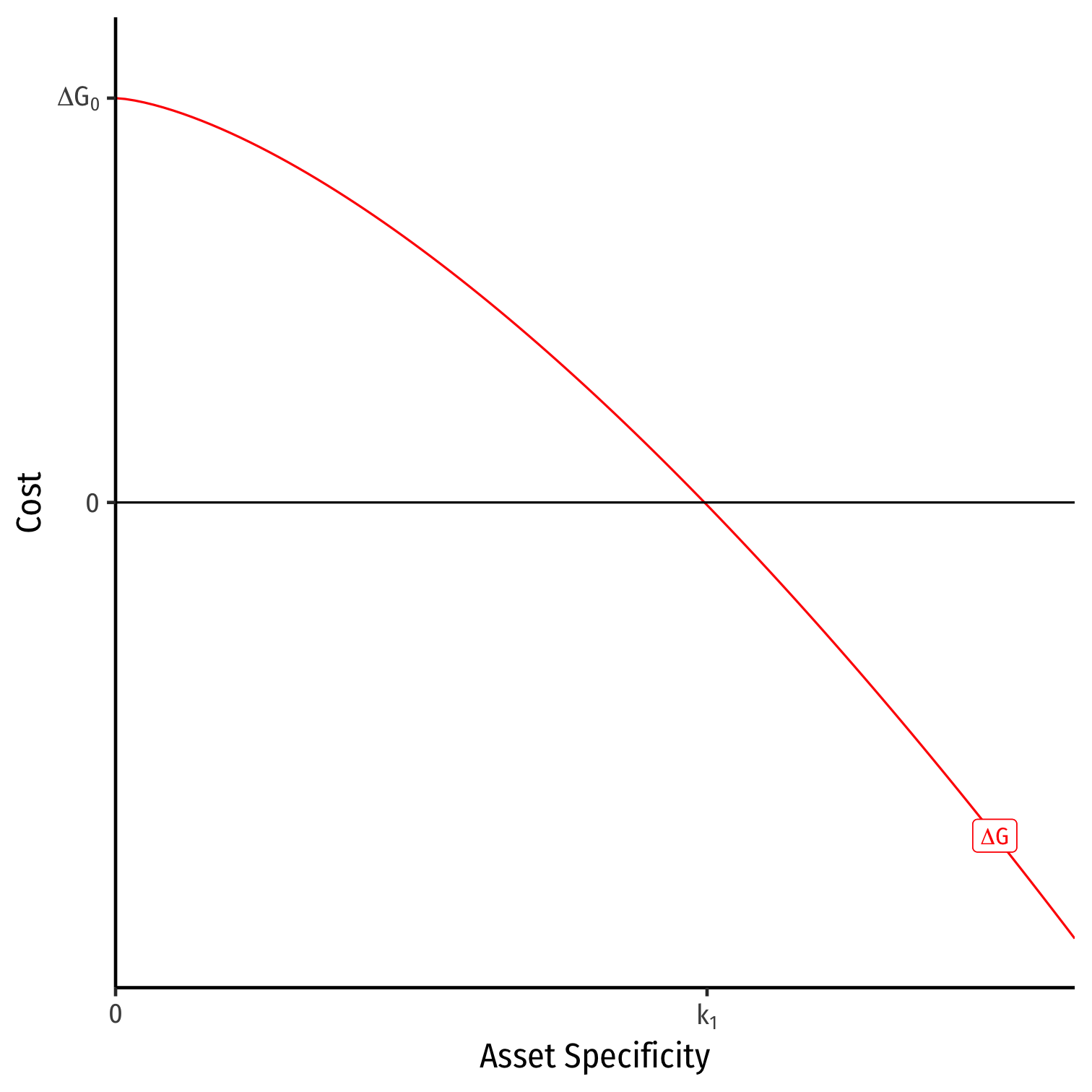

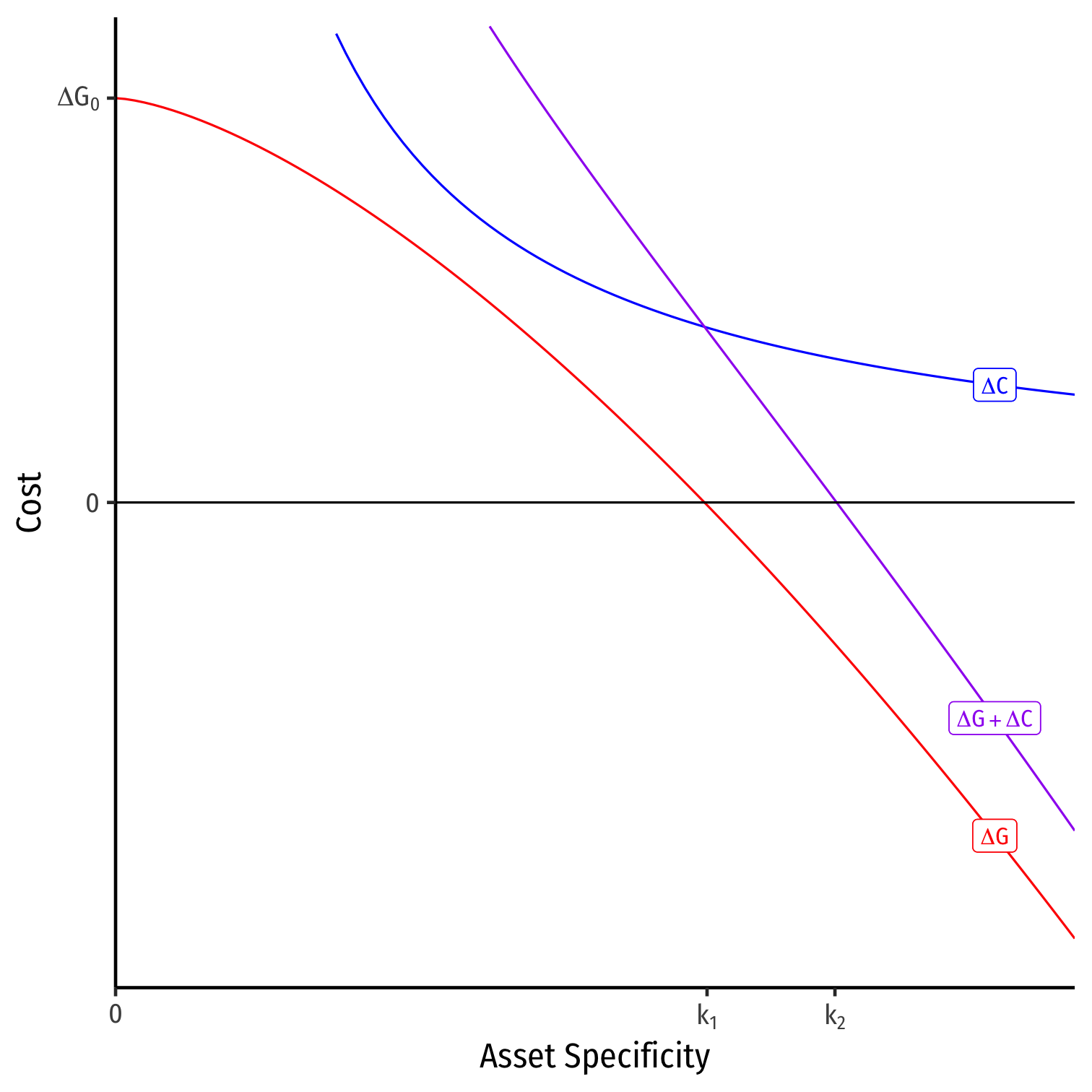

Asset Specificity: Simple Heuristic Model

- ΔG: difference in governance cost of organization (firm) vs. market

- ΔG(0): advantages of markets > costs of asset specificity

- declines as assets are more specific (market contracts become disadvantageous beyond k1)

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

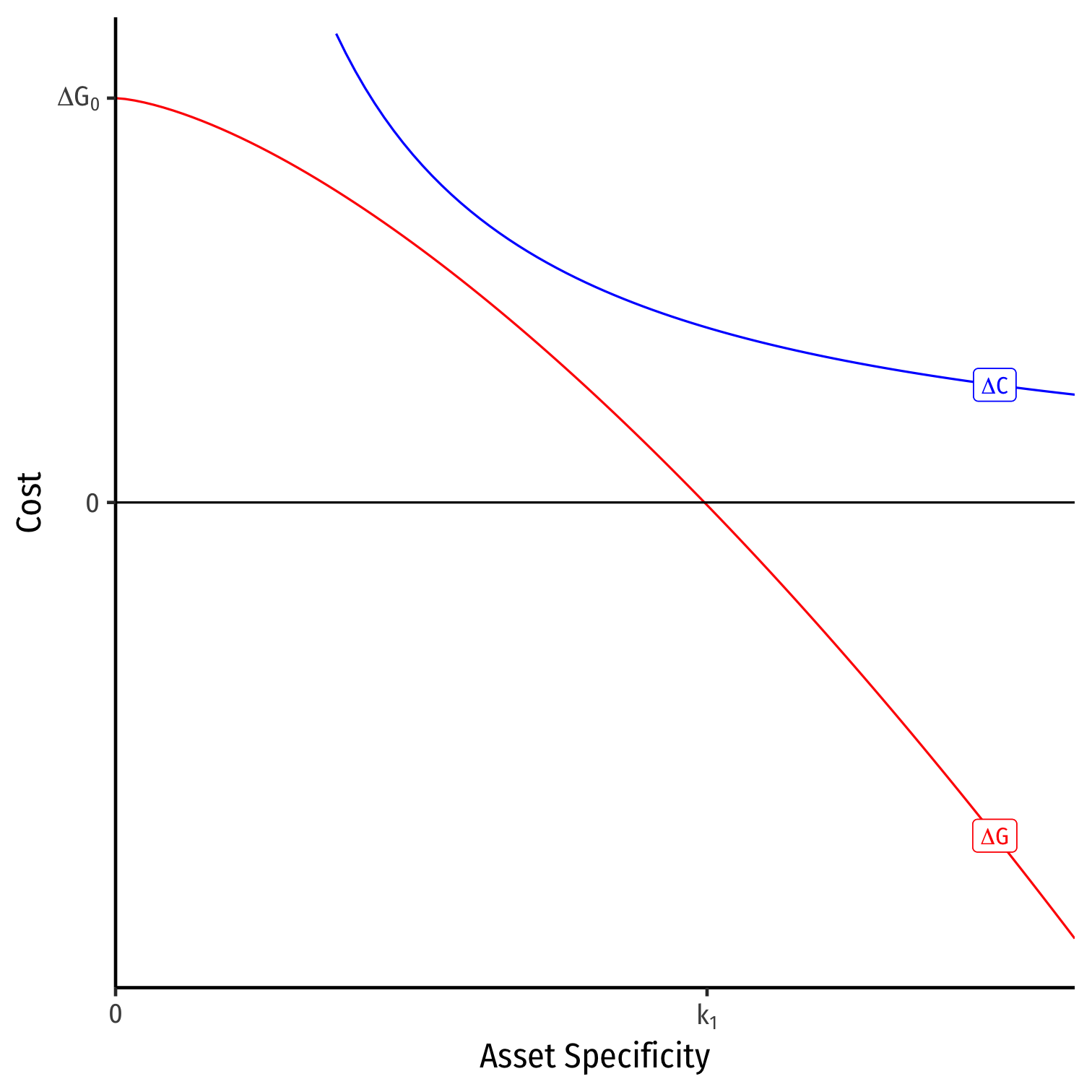

Asset Specificity: Simple Heuristic Model

ΔG: difference in governance cost of organization (firm) vs. market

- ΔG(0): advantages of markets > costs of asset specificity

- declines as assets are more specific (market contracts become disadvantageous beyond k1)

ΔC: difference in production costs of organization (firm) vs. market

- advantages of markets > organization (firm)

- declines as assets get more specific, but never fully reduced to zero (same as market)

- since ΔC>0, firm will never internalize for production cost reasons alone

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

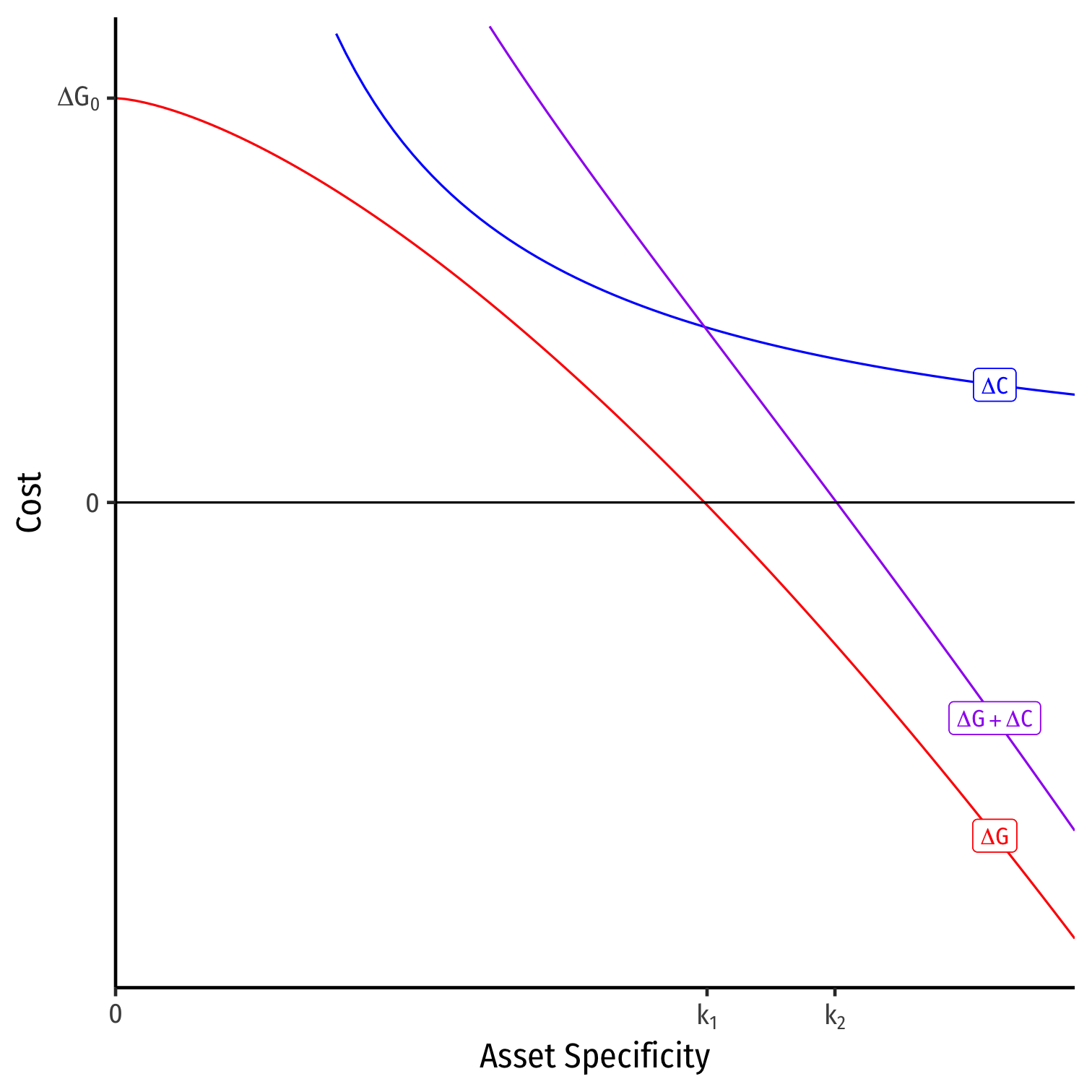

Asset Specificity: Simple Heuristic Model

ΔG: difference in governance cost of organization (firm) vs. market

- ΔG(0): advantages of markets > costs of asset specificity

- declines as assets are more specific (market contracts become disadvantageous beyond k1)

ΔC: difference in production costs of organization (firm) vs. market

- advantages of markets > organization (firm)

- declines as assets get more specific, but never fully reduced to zero (same as market)

- since ΔC>0, firm will never internalize for production cost reasons alone

- ΔC+ΔG: total cost difference between organization and market

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

Asset Specificity: Simple Heuristic Model

At low levels of asset specificity (k<k2), market transactions are lower cost than organization

- contract & buy most things

- since ΔC>0, firm will never internalize for production cost reasons alone

At higher levels of asset specificity (k>k2), organization is lower cost than market

- produce most things internally

At modest levels of asset specificity k2, no clear superior mode, may be a combination

- make some things, buy some things

Based on Riordan and Williamson, 1985

Asset Specificity: Example

Suppose one party owns a generic asset - trucks

- High opportunity cost - easily resold or put to other uses

Another party owns a highly specific asset - highly specialized machines

- Next best alternative use is a boat anchor

Asset Specificity: Example

Suppose a contract between them creates $50,000 of joint net value for the owner of the generic asset and the owner of the specific asset

Can't recontract until next year

Once the contract is signed, the owner of the generic asset threatens to pull out of the contract

- Demands $49,000 of the "quasirents of cooperation"

They Are Altering The Deal...

...Pray They Don't Alter it Any Futher

Asset Specificity: Example

Foreseeing such contractual hazards parties will be reluctant to cooperate

Or will choose a less specialized and less efficient technology

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model

Two players, Party A and Party B

Party A incurs a sunk cost -C once contract is signed C>0.10π

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model

- Subgame perfect Nash equilibrium:

{(Generic Tech, Give In), (Hold Up) }†

- Outcome: Party A uses less efficient Generic Tech

† Strategies for Party A chosen at (A.1, A.2) and Party B at (B.1)

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model: Hostages

Suppose before Party A makes their initial decision, Party B supplies a bond or a hostage to Party A

Hostage will be forfeited if Party B does not Fulfill their contract:

- Party A gets αH−C

- Party B gets −H

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model: Hostages

- H: value of hostage to Party B

α: fraction of H that is valuable to Party A

- α=0: no value to A

- α=1: cash

If αH>0.10π+C, Party A will Not Give In to a Hold Up, and Party B will thus Fulfill

A Game-Theoretic Hold-Up Model

- Subgame perfect Nash equilibrium:

{(Specialized Contract, Don't Give In), (Fulfill) }†

- Outcome: Party A uses more efficient Specialized Contract, and generates more value for both Party A and Party B

† Strategies for Party A chosen at (A.1, A.2) and Party B at (B.1)

Using Hostages to Support Exchange

Using Hostages to Support Exchange

Williamson, Oliver E, 1983, "Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support Exchange," American Economic Review

Double Marginalization Problem

Double Marginalization Problem

Double Marginalization Problem

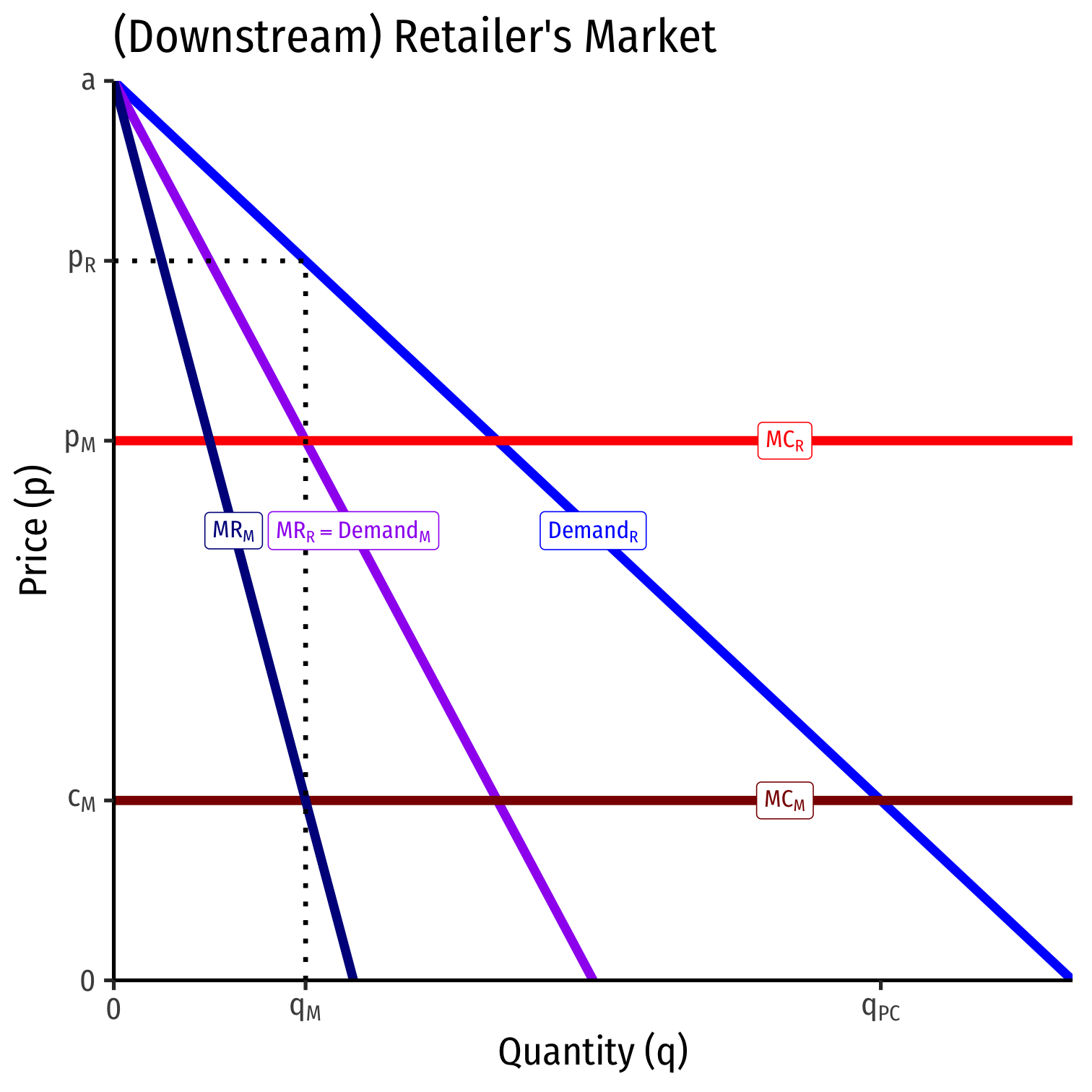

Consider a simple model of two-stage production:

- Manufacturing (“upstream”)

- Retailing (“downstream”)

Assume each unit of final product (sold by retailer to consumers) requires 1 unit of input (sold by manufacturer to retailer)

- e.g. 1 engine for 1 car

Each stage is a separate market, which could be competitive or monopolistic

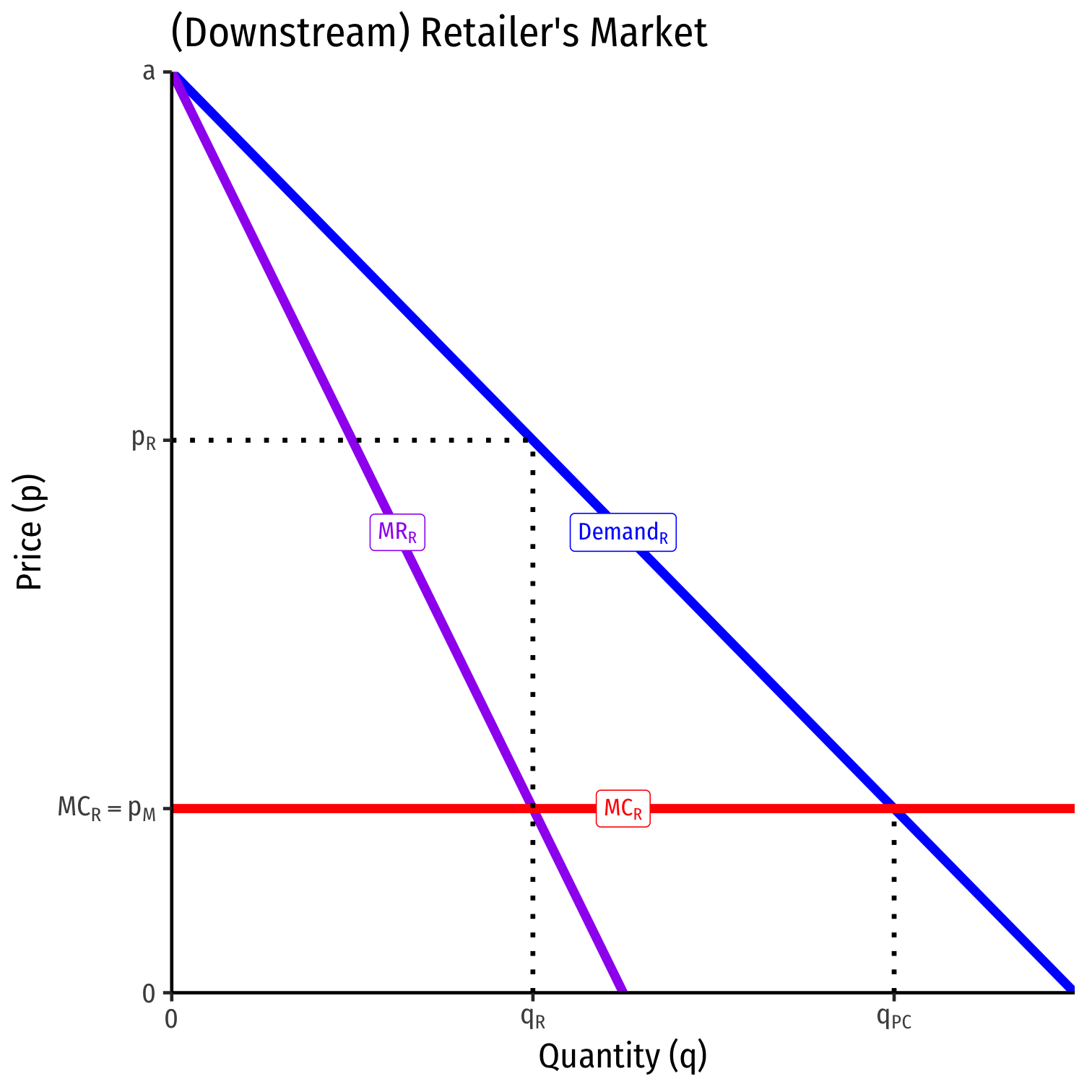

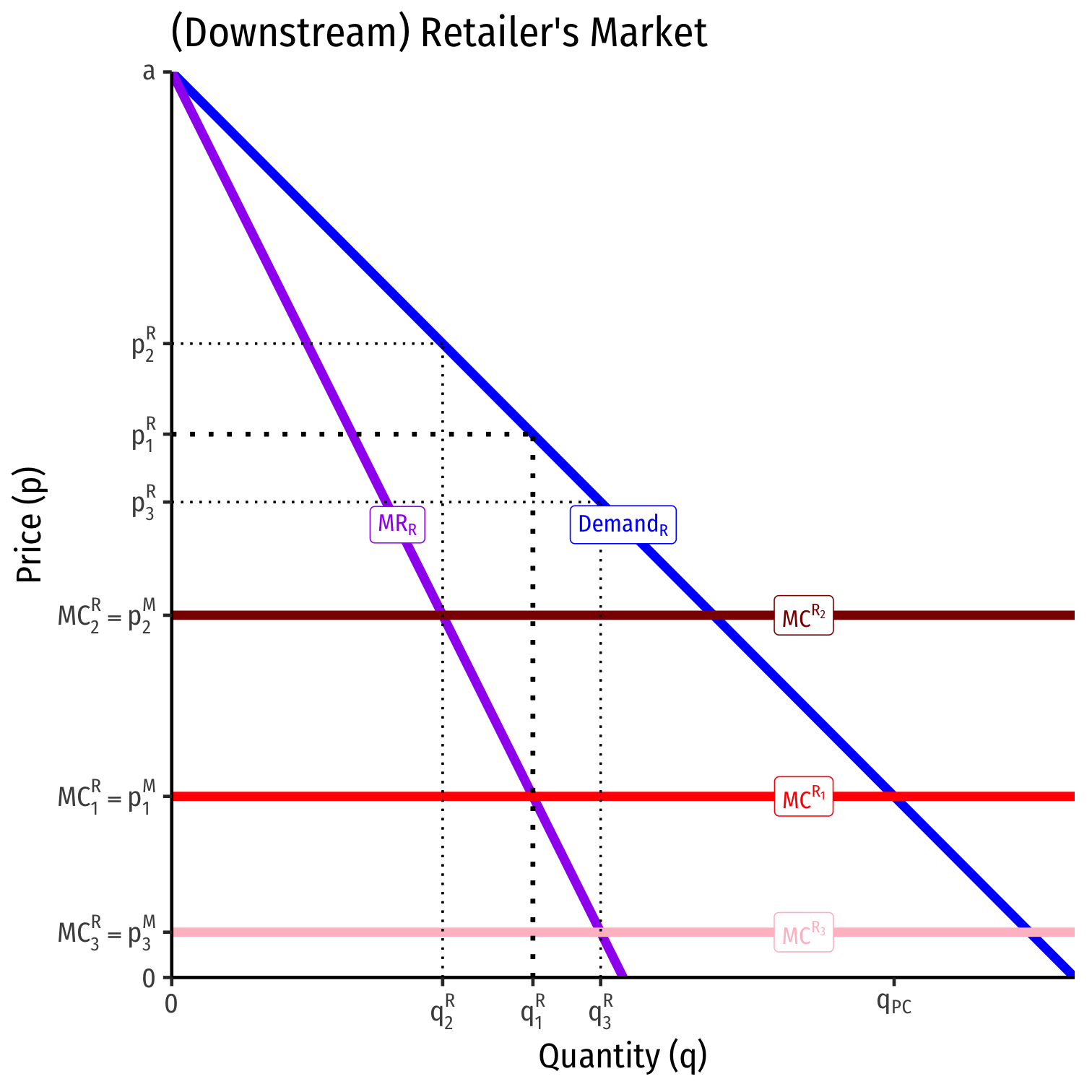

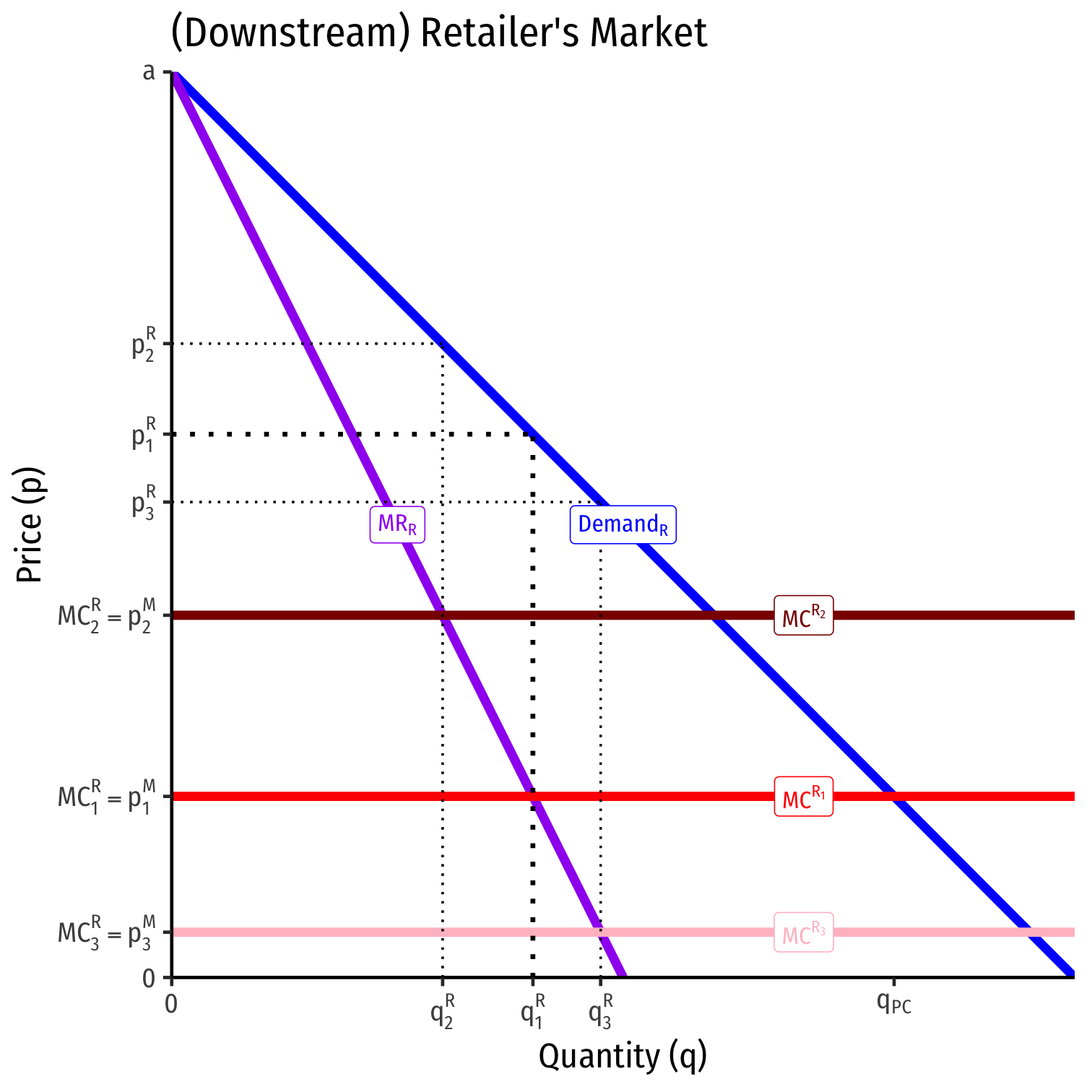

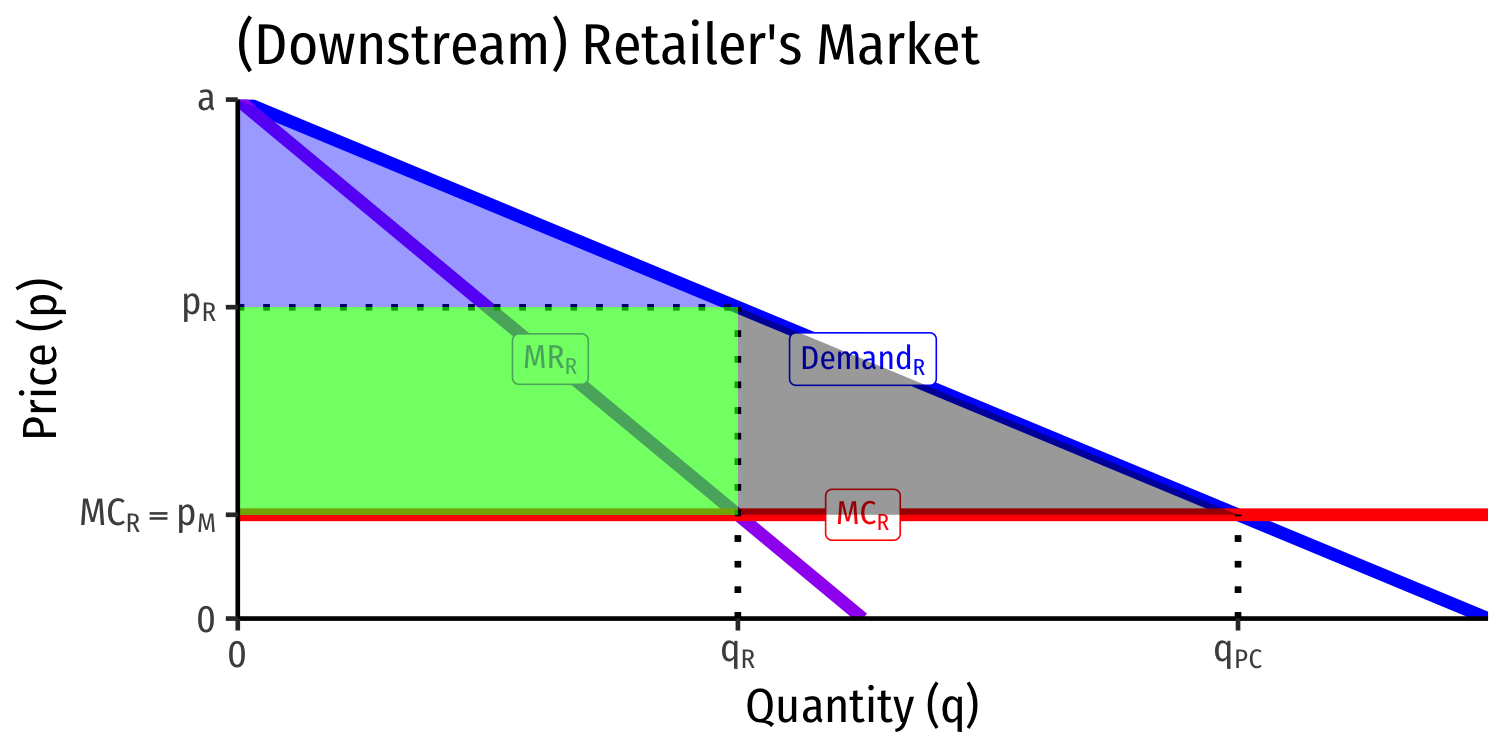

Double Marginalization Problem

MCR for Retailer = price for Manufacturer’s output (MCR=pM)

Retailer sets MR=MC at qR and marks up pR>MCR to consumers

Double Marginalization Problem

MCR for Retailer = price for Manufacturer’s output (MCR=pM)

Retailer sets MR=MC at qR and marks up pR>MCR to consumers

Retailer earns Profits

Generates Consumer surplus and DWL

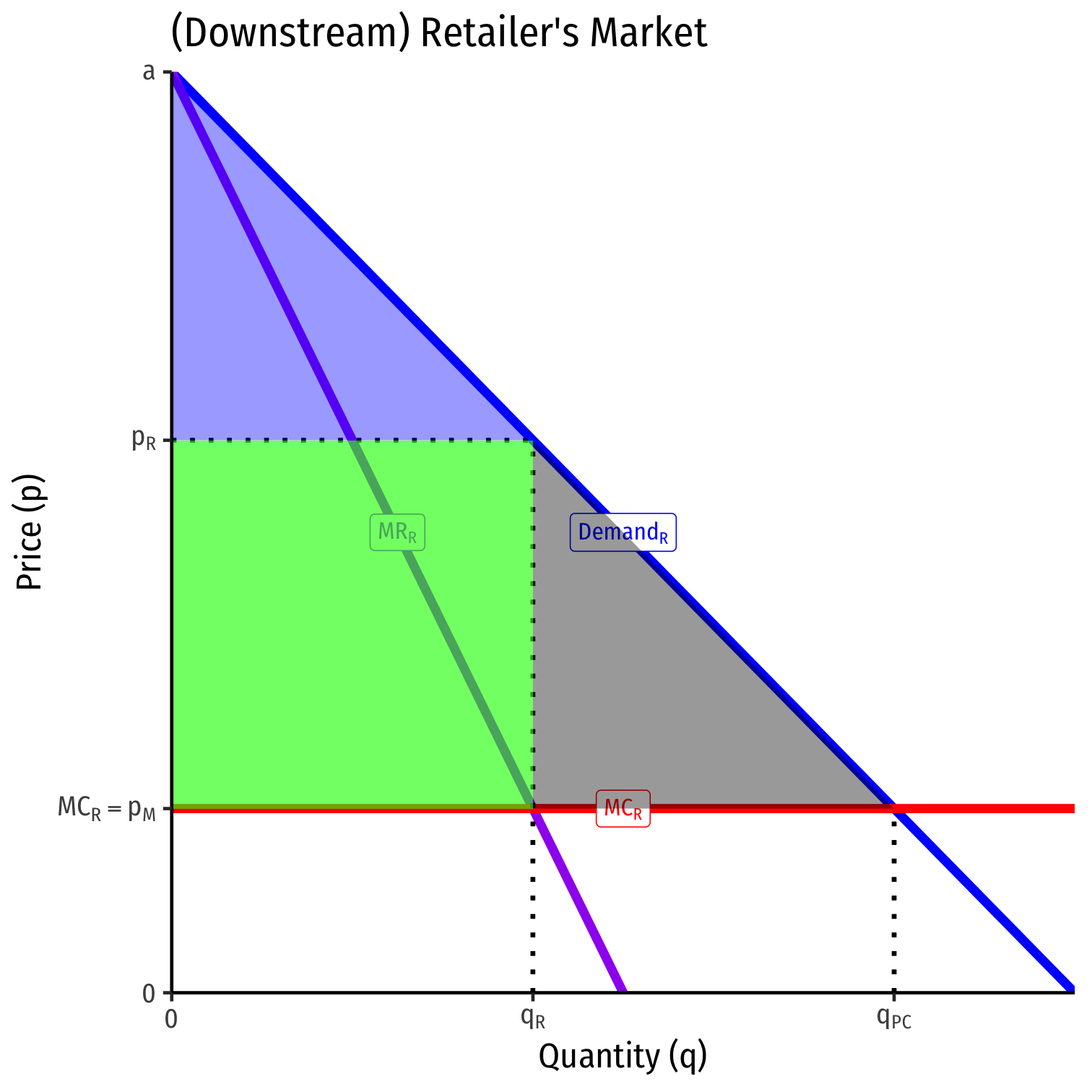

Double Marginalization Problem

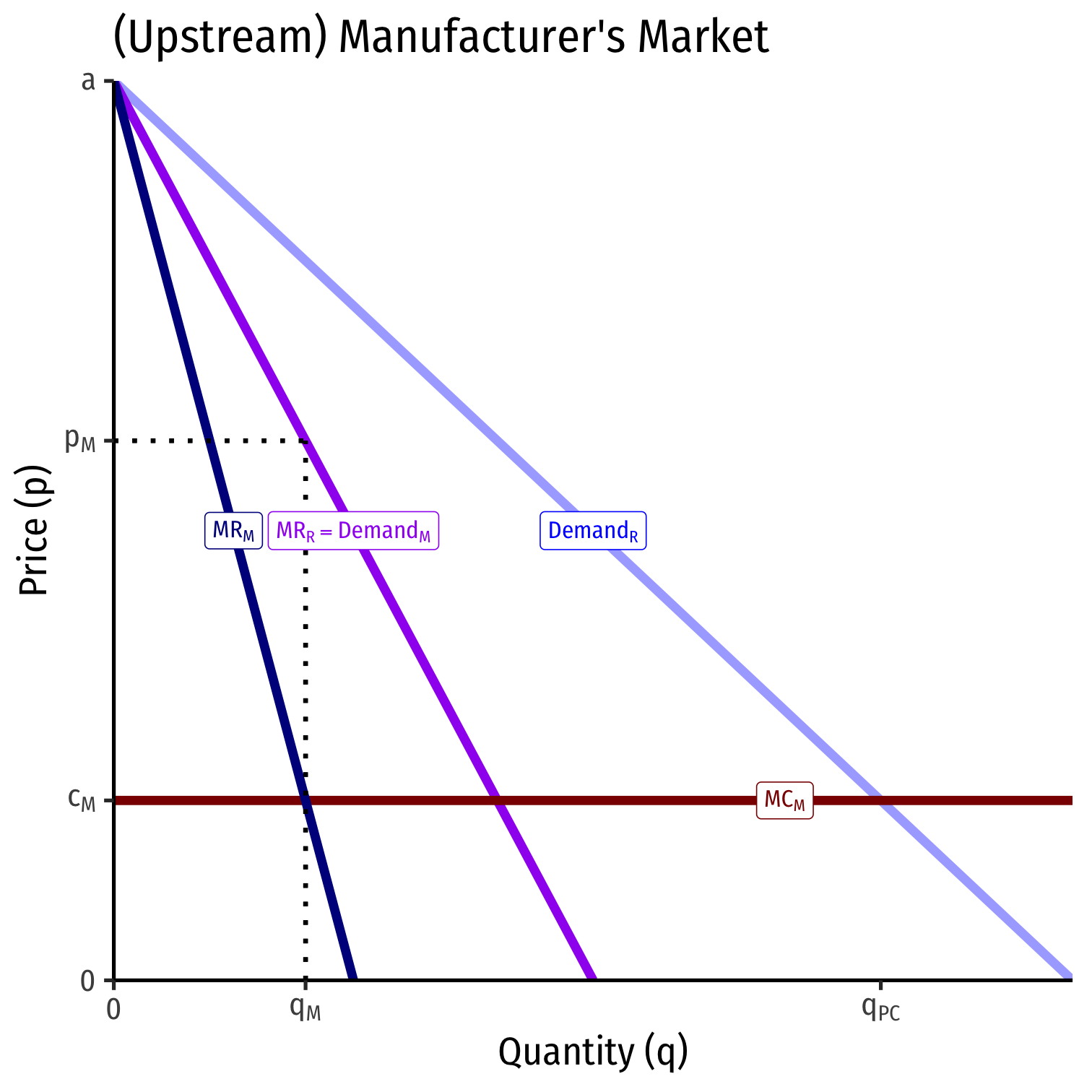

Note that Retailer's MR curve is the demand curve for the Manufacturer

If Manufacturer were to raise/lower price, Retailer would buy qR where MRR=MCR

- Recall Retailer's MCR is Manufacturer's PM!

Double Marginalization Problem

Note that Retailer's MR curve is the demand curve for the Manufacturer

If Manufacturer were to raise/lower price, Retailer would buy qR where MRR=MCR

- Recall Retailer's MCR is Manufacturer's PM!

Double Marginalization Problem

Note that Retailer's MR curve is the demand curve for the Manufacturer

If Manufacturer were to raise/lower price, Retailer would buy qR where MRR=MCR

- Recall Retailer's MCR is Manufacturer's PM!

Describes qR for every possible PM!

So what price PM will the Manufacturer set??

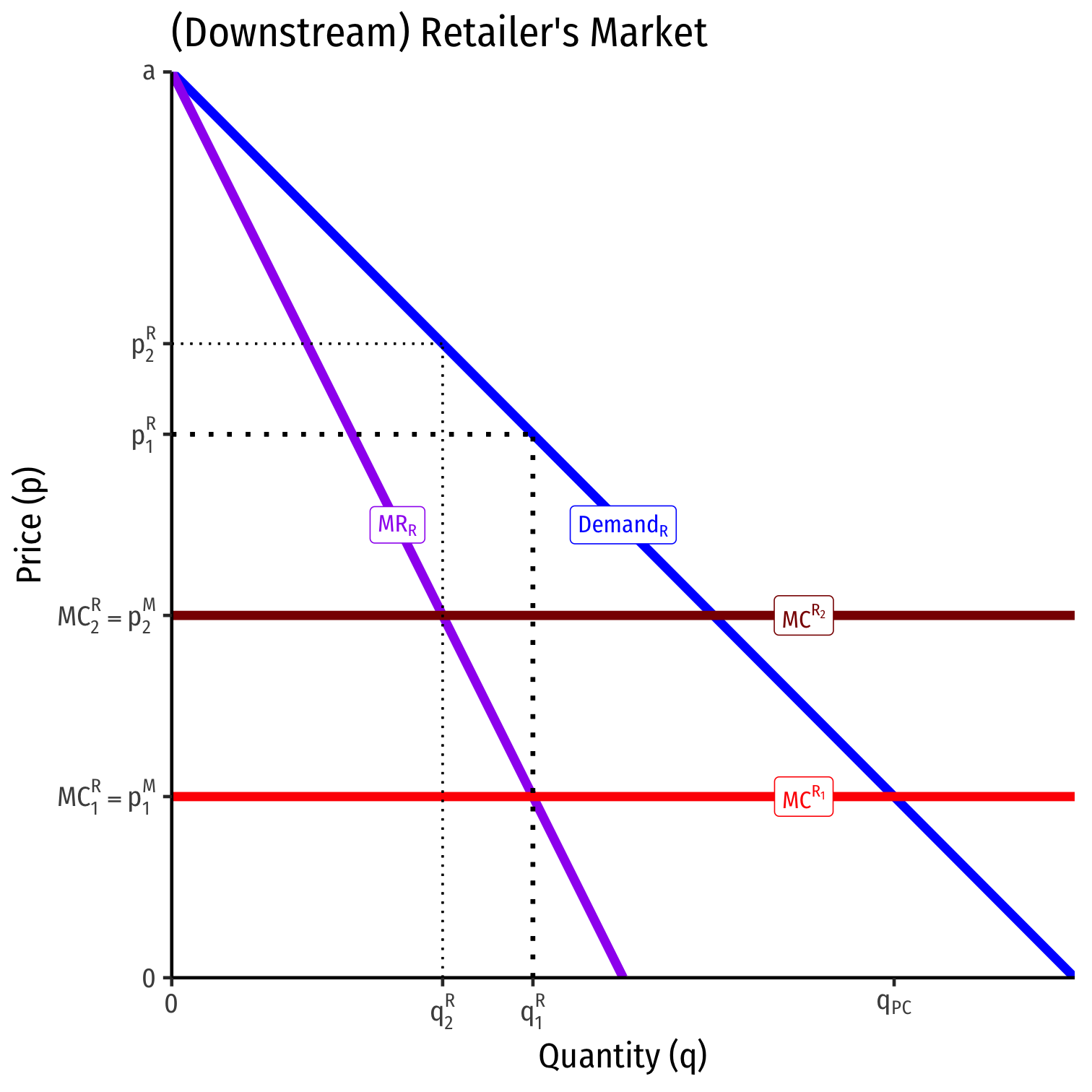

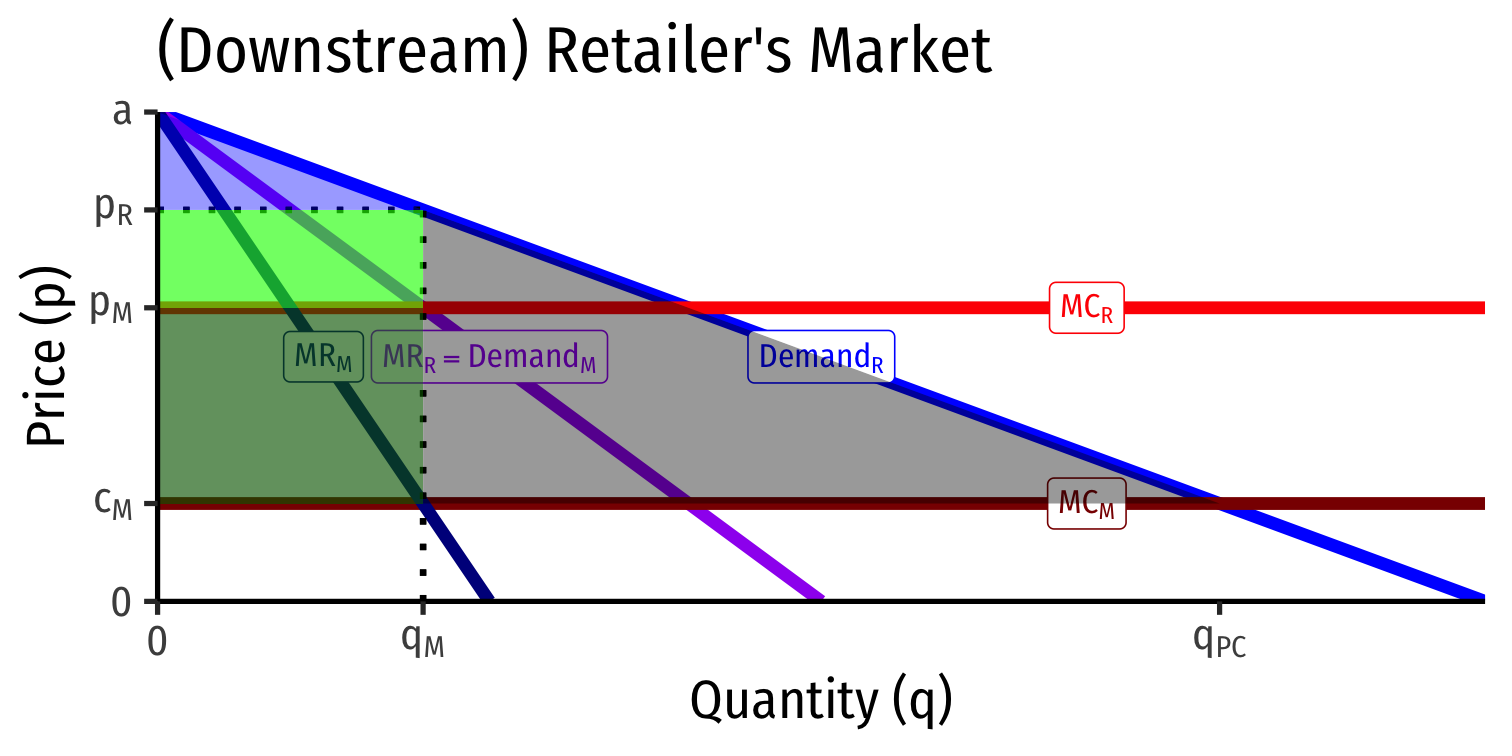

Double Marginalization Problem

Since Manufacturer's MRM curve is Retailer's Demand curve, consider Retailer's MRR curve

- Starting at a, with twice the slope of MRM!

It will set its own MCM=MRM

Then markup the price to pM (most Retailer is willing to pay!)

Double Marginalization Problem

Since Manufacturer's MRM curve is Retailer's Demand curve, consider Retailer's MRR curve

- Starting at a, with twice the slope of MRM!

It will set its own MCM=MRM

Then markup the price to pM (most Retailer is willing to pay!)

pM becomes the new MCR for Retailer

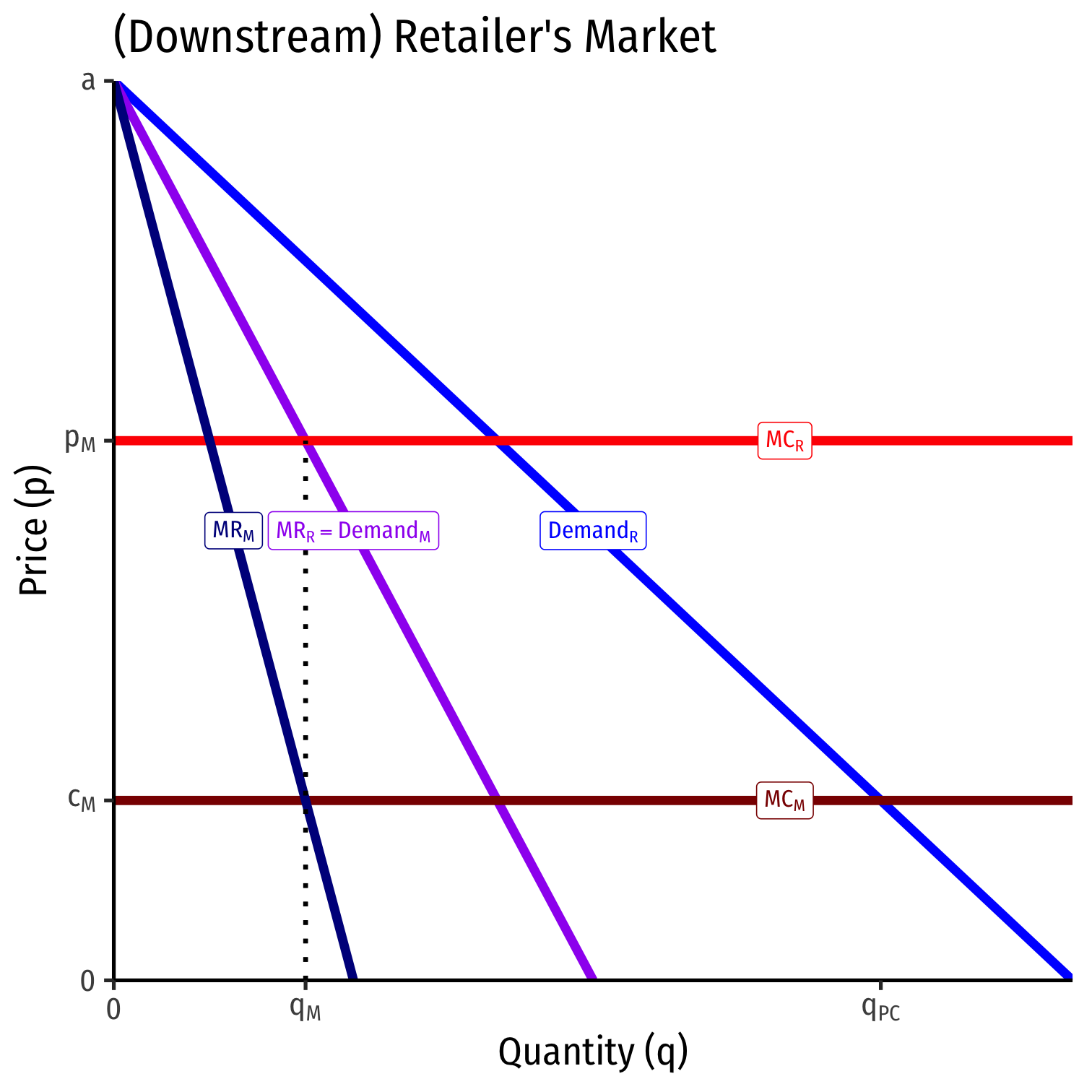

Double Marginalization Problem

Retailer takes this higher pM=MCR and sets it equal to its own MRR

Marks up the price to pR

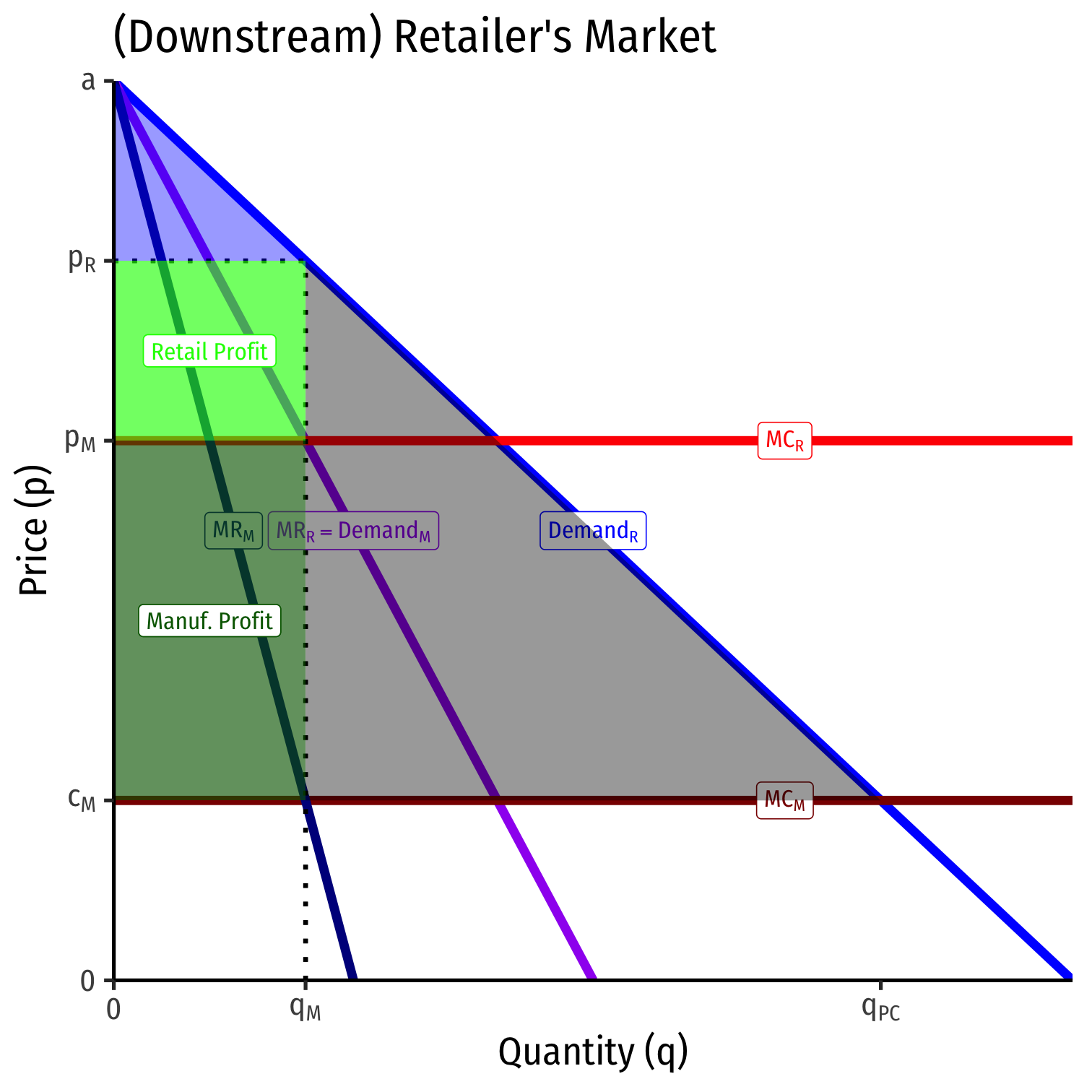

Double Marginalization Problem

Manufacturer earns some profit

Retailer extracts some of this profit (darker)

Less Consumer Surplus

Much greater DWL from double markup

Double Marginalization Problem

With bilateral monopoly, a double-markup causing:

Much less consumer surplus

Much more DWL

Less total profit (and it's split between Manufacturer & Retailer)

Vertical Integration

Vertical Integration

One solution to this problem is vertical integration: the firm internalizes a stage of production in the supply chain

- Often by buying its supplier

Avoids hold up problems and post-contractual opportunism

Vertical Integration

- Antitrust implications: vertical integration may not be done to intentionally create market power, but to economize on transaction costs from asset specificity

Vertical Integration

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“[A]s assets become more specific and more appropriable quasi rents are created (and therefore the gains from opportunistic behavior increases), the costs of contracting will generally increase more than the costs of vertical integration. Hence, ceterus paribus, we are more likely to observe vertical integration,” (p.298).

Vertical Integration

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“We maintain that if an asset has a substantial portion of quasi rent which is strongly dependent upon some other particular asset, both assets will tend to be owned by one party,” (p.300).

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Vertical Integration

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“The primary alternative to vertical integration as a solution to the general problem of opportunistic behavior is some form of economically enforceable long-term contract,” (p. 302).

Vertical Integration

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Long-term contracts used as alternatives to vertical integration can be assumed to take two forms: (1) an explicitly stated contractual guarantee legally enforced by the government or some other outside institution, or (2) an implicit contractual guarantee enforced by the market mechanism of withdrawing future business if opportunistic behavior occurs...[However, they are] often very costly solutions. They entail costs of specifying possible contingencies and the policing and litigation costs of detecting violations and enforcing the contract in the courts..every contingency cannot be cheaply specified in a contract or even known and because legal redress is expensive...” (p.303).

GM and Fisher Body Example

GM and Fisher Body Example

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“The manufacture of dies for stamping parts in accordance with the above specifications [for a Mustang or Ford model] gives a value to these dies specialized to Ford, which implies an appropriable quasi rent in those dies...once the large sunk fixed cost of the specific investment in the dies is made, the incentive for Ford to opportunistically renegotiate a lower price at which it will accept body parts from the independent die owner may be large. Similarly, if there is a large cost to Ford from the production delay of obtaining an alternative supplier of the specific body parts, the independent die owner may be able to capture quasi rents by demanding a revised higher price for the parts. Since the opportunity to lose the specialized quasi rent of assets is a debilitating prospect, neither party would invest in such equipment. Joint ownership of designs and dies removes this incentive to attempt appropriation,” (p.308).

GM and Fisher Body Example

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“[I]n 1919 General Motors entered a ten-year contractual agreement with Fisher Body for the supply of closed auto bodies. In order to encourage Fisher Body to make the required specific investment, this contract had an exclusive dealing clause whereby General Motors agreed to buy substantially all its closed bodies from Fisher. This exclusive dealing arrangement significantly reduced the possibility of General Motors acting opportunistically by demanding a lower price for the bodies after Fisher made the specific investment in production capacity,”

GM and Fisher Body Example

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“But large opportunities were created by this exclusive dealing clause for Fisher to take advantage of General Motors, namely to demand a monopoly price for the bodies. Therefore, the contract attempted to fix the price which Fisher could charge for the bodies supplied to General Motors...The price was set on a cost plus 17.6 per cent basis [and had other provisions to protect GM].”

GM and Fisher Body Example

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Unfortunately, however, these complex contractual pricing provisions did not work out in practice. The demand conditions facing General Motors and Fisher Body changed dramatically over the next few years. There was a large increase in the demand for automobiles and a significant shift away from open bodies to the closed body styles supplied by Fisher. Meanwhile, General Motors was very unhappy with the price it was being charged by its now very important supplier, Fisher...By 1924, General Motors had found the Fisher contractual relationship intolerable and began negotiations for purchase of the remaining stock in Fisher Body, culminating in a final merger agreement in 1926,” (pp.309-310).

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326