4.4 — Contractual Restraints

ECON 326 • Industrial Organization • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/ioS23

ioS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Recap

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Coase's fundamental insight [was] that transaction, coordination, and contracting costs must be considered explicitly in explaining the extent of vertical integration...[We] explore one particular cost of using the market system-the possibility of postcontractual opportunistic behavior,” (p.297)

“The particular circumstance we emphasize as likely to produce a serious threat of this type of reneging on contracts is the presence of appropriable specialized quasi rents. After a specific investment is made and such quasi rents are created, the possibility of opportunistic behavior is very real. Following Coase's framework, this problem can be solved in two possible ways: vertical integration or contracts,” (p.298)

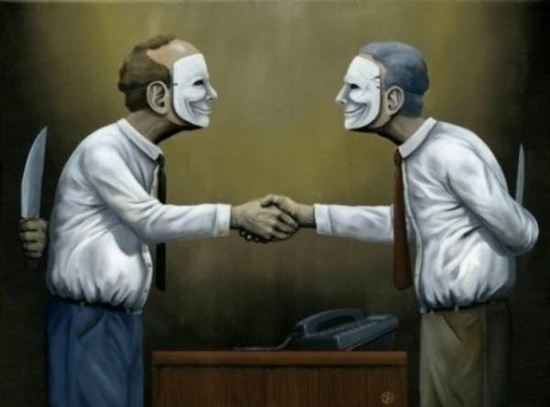

Solutions to Minimize Post-Contractual Opportunism

Recap: a contract removes parties from a competitive market and creates bilateral dependency between them

- incentives for post-contractual opportunism

- parties may try to capture more quasi-rents from cooperation

- may be caused by asset specificity

Two general solutions:

- Contracting solutions: write a better contract

- Vertical integration: have one party buy the other

Let's Talk More About Contracts

Contract: an agreement through which exchange is mediated

- basically: a promise

- may be written down or implied

- enforceable in courts

Common law recognizes a contract to be valid if there is:

- Offer and acceptance (a “meeting of the minds”)

- Consideration (something of value is to be transferred)

- An “intention to be legally bound”

Contracting

Learn more in my Economics of the Law course

Valid contracts create legal rights and duties that are enforceable by courts

An aggrieved party can sue the other party for breach of contract, and court will enforce judgment

Courts typically require defendant to pay damages

- may invalidate a contract

- or require “specific performance” (very rare)

Complete Contracts

A complete contract (theoretically) specifies all actions or transfers that parties must take under every possible contingency

In the real world of uncertainty (and transaction costs), complete contracts are impossible (and costly)

Instead people maximize their expected utility given limited information at the time (“bounded rationality”)

Consequences of Incomplete Contracts

Agreements are always incomplete contracts, actions for many (unforeseen) contingencies are left unspecified

Even for specified actions and contingencies, outcomes are indeterminate due to enforcement costs

- argument about facts, law, interpretation

- litigation is slow, very costly

Gives rise to opportunism (shirking, fraud, renegotiation, hold-up, etc)

Vertical Integration

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“The primary alternative to vertical integration as a solution to the general problem of opportunistic behavior is some form of economically enforceable long-term contract,” (p. 302).

Vertical Integration vs. Contract Solutions

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Long-term contracts used as alternatives to vertical integration can be assumed to take two forms: (1) an explicitly stated contractual guarantee legally enforced by the government or some other outside institution, or (2) an implicit contractual guarantee enforced by the market mechanism of withdrawing future business if opportunistic behavior occurs...[However, they are] often very costly solutions. They entail costs of specifying possible contingencies and the policing and litigation costs of detecting violations and enforcing the contract in the courts,” (p.303)

Vertical Integration vs. Contract Solutions

Vertical integration creates its own administrative & agency costs

- And others we’ll see later today

- Not always an efficient response to opportunism

Alternative contractual solutions exist, often called “vertical restraints”, e.g.:

- Exclusive dealing

- Territorial restraints

- Franchising agreements

- Resale price maintenance (RPM)

Examples of Contractual Restraints

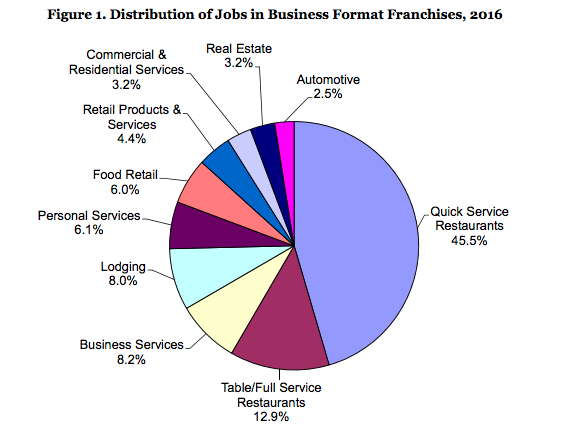

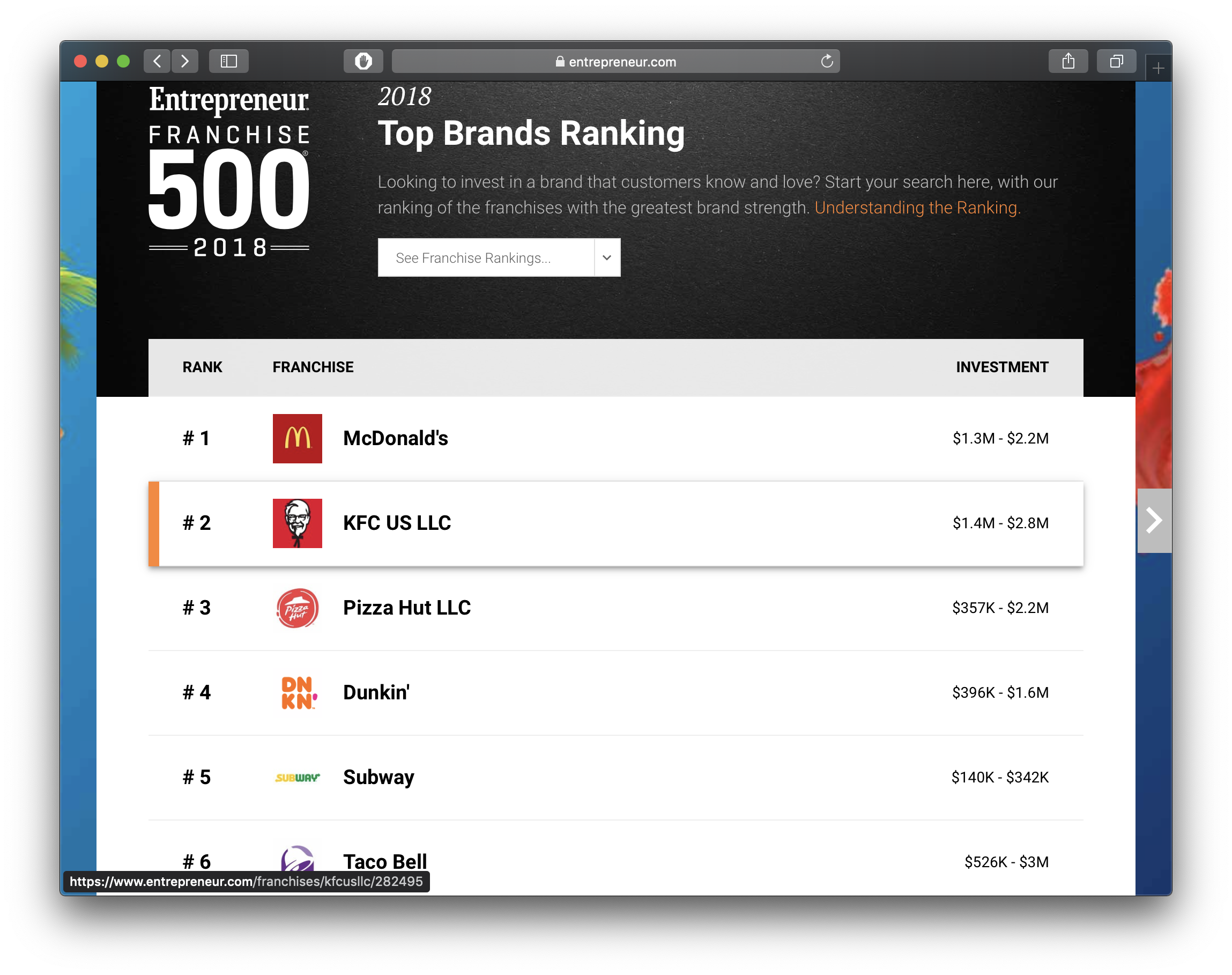

Franchising

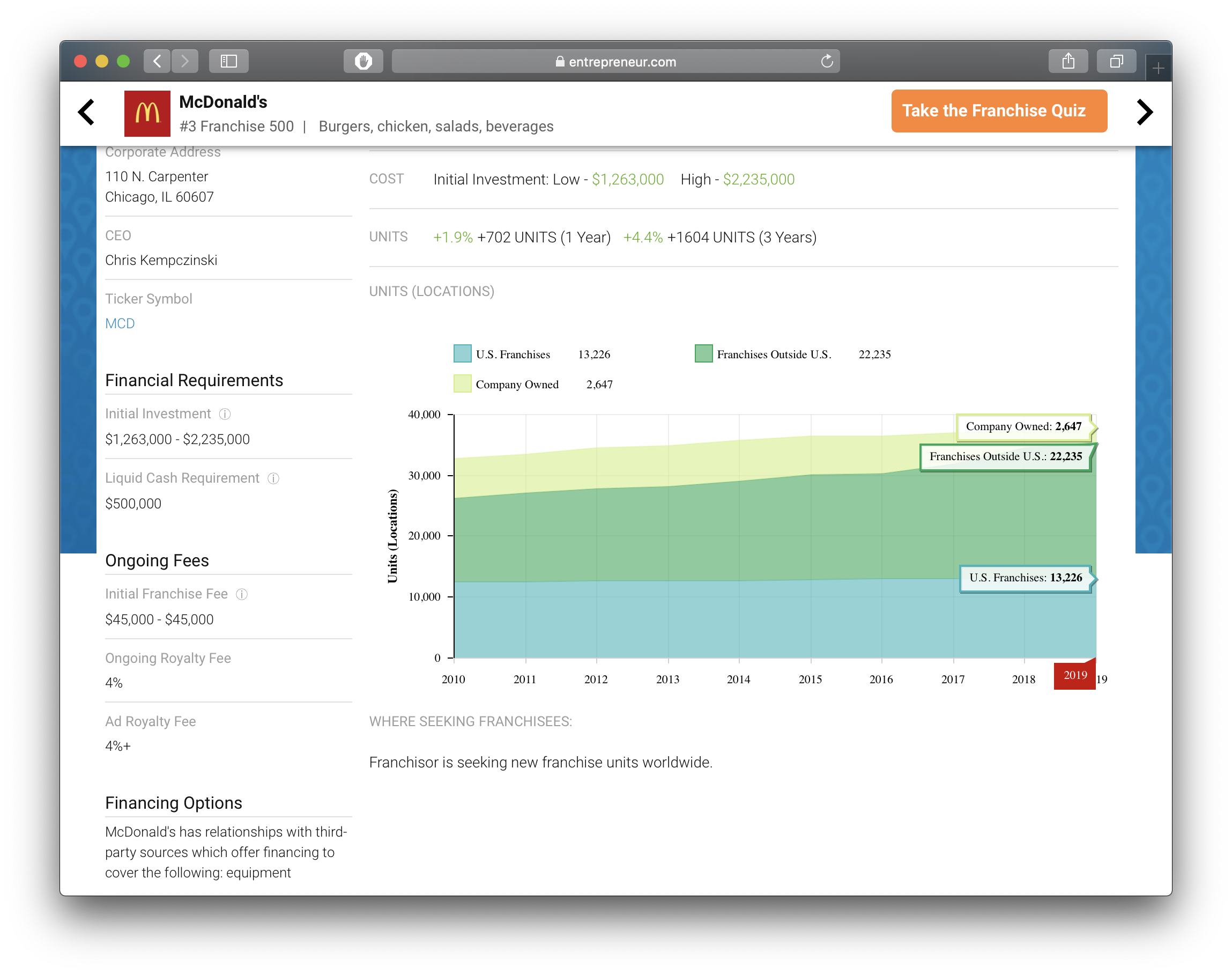

Franchise contract: a franchisor leases use of its key nontangible assets to franchisee

Franchisor’s non-tangible assets leased: business model, use of brand name, logos, trademarks, trade secrets, know-how, etc.

Franchisee as entrepreneur owns/rents and manages physical assets (retail location, capital equipment, etc) & bears the risk

Franchisee pays franchisor fees & royalties to license franchisor’s brand

Franchising

Economies of scale with national (“corporate”) advertising, business strategy, name-recognition for all franchisees licensing the same brand

Franchise contract contains many restrictions on what franchisee may do with franchisor’s brand, why?

Franchising

- Parties could free ride off the brand name!

- All parties make joint investments in the brand name

- Benefits of high quality brand are shared, not owned entirely by any party — a positive externality or public good

- Incentives to shirk and underinvest in quality!

Franchising

- “Horizontal” free riding:

- Many franchisees share the franchisor’s brand name & reputation

- Each franchisee will undersupply investment to maintain brand quality

Franchising

- “Vertical” free riding:

- Franchisor’s income comes from fees and royalties from franchisees, it’s not the residual claimaint

- Each franchisee is a residual claimant, earns own profits off of their own sales (franchise fee is a cost to them)

- Franchisor will want to undersupply investments in advertising, strategy, quality provision (doesn’t fully internalize the value created)

Franchising

Franchisor has incentive to find efficient way to monitor itself and franchisees to maintain quality

- As in Alchian and Demsetz (1972) and Jensen and Meckling (1976)!

- Franchisor can charge higher fees from a more valuable brand name

Common stipulations in franchising agreements:

- Franchisees may need to use specific equipment (e.g. certain shapes of buildings for fast food restaurants, hotels)

- Franchisees’ employees often need to go through common ("corporate") training programs to maintain quality and consistency

Exclusive Dealing/Tie-In Contracts

Many contracts (including franchises) have exclusive dealing or tie-in agreements that require firm (e.g. franchisee) to purchase inputs exclusively from other firm (e.g. franchisor) or a designated third-party

Sound like market power/price discrimination?

Efficient response to horizontal & vertical free riding problem

- Easy to monitor quality

Examples

Territorial Restraints

Franchisors often include territorial restraints to create exclusive territories for franchisees

Removes competition between franchisees in geographic area

Avoids cannabalizing one another and diluting the franchisor’s brand

Territorial Restraints?

Resale Price Maintenance

A manufacturer in long-term contracts with retailers will often require retail or resale price maintenance (RPM):

- Manufacturer often sets a maximum or minimum price that retailers can charge for their products

Sound like a cartel agreement?

Or maybe manufacturer trying to prevent retailers from horizontal free riding on maintaining the manufacturer’s brand

Resale Price Maintenance

Lester G Telser

1931-

“If some retailers [provide extra] services [such as advertising, pre-sale demonstrations, etc] and ask for a corespondingly higher price whereas others do not provide the services and offer to sell the product to consumersat a lower price then an unstable situation emerges. Sales are diverted from the retailers who do provide the special services at the higher price to the retailers who do not provide the special services and offer to sell the product at the lower price....A customer,because of the special services provide by one retailer, is persuaded to buy the product. But he purchases the product from another paying the latter a lower price. In this way the retailers who do not provide the special services get a free ride at the expense of those who have convinced consumers to buy the product,” (pp. 91-92).

Resale Price Maintenance

Lester G Telser

1931-

“[The manufacturer can prevent] this by establishing a minimum retail price that guarantees a minimum gross markup. Therefore retailers are forced to compete by providing special services with the product and not by reducing the retail price,” (pp. 91-92).

Contracting Over Specific Human Capital

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“When specific human capital is involved, the opportunism problem is often more complex and, because of laws prohibiting slavery, the solution is generally some form of explicit or implicit contract rather than vertical integration,” (p.315)

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Contracting Over Specific Human Capital

When the specific asset is human capital, firms generally resort to long-term contracts, not vertical integration

Firms cannot own their labor inputs!

Compulsory arbitration clauses

- instead of threats of costly litigation

Bonds that employers or employees forfeit (a “hostage”) for bad behavior, or leaving the company too soon

- stock options that take time to vest, etc.

Contracting Over Specific Human Capital

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Contractual provisions specifying compulsory arbitration or more directly imposing costs on the opportunistic party (for example, via bonding) are alternatives often employed to economize on litigation costs and to create flexibility without specifying every possible contingency and quality dimension of the transaction,” (p.303)

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Since every contingency cannot be cheaply specified in a contract or even known and because legal redress is expensive, transactors will generally also rely on an implicit type of long-term contract that employs a market rather than legal enforcement mechanism, namely, the imposition of a capital loss by the withdrawal of expected future business. This goodwill market-enforcement mechanism undoubtedly is a major element of the contractual alternative to vertical integration,” (p.303)

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“One way in which this market mechanism of contract enforcement may operate is by offering to the potential cheater a future ‘premium,’ more precisely, a price sufficiently greater than average variable (that is, avoidable) cost to assure a quasi-rent stream that will exceed the potential gain from cheating. The present-discounted value of this future premium stream must be greater than any increase in wealth that could be obtained by the potential cheater if he, in fact, cheated and were terminated. The offer of such a long-term relationship with the potential cheater will eliminate systematic opportunistic behavior,” (p.304).

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“The larger the potential one-time ‘theft’ by cheating (the longer and more costly to detect a violation, enforce the contract, switch suppliers, and so forth) and the shorter the expected continuing business relationship, the higher this premium will be in a nondeceiving equilibrium. This may therefore partially explain both the reliance by firms on long-term implicit contracts with particular suppliers and the existence of reciprocity agreements among firms...The threat of termination of this relationship mutually suppresses opportunistic behavior. The premium stream can be usefully thought of as insurance payments made by the firm to prevent cheating,” (pp.304-5)

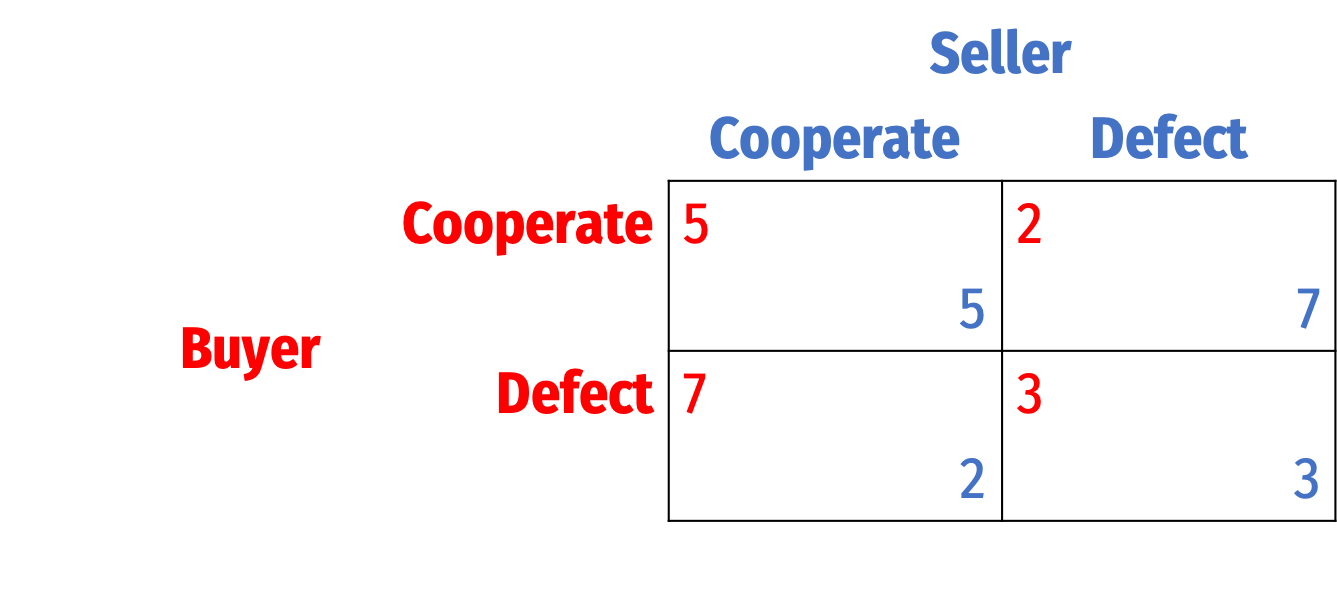

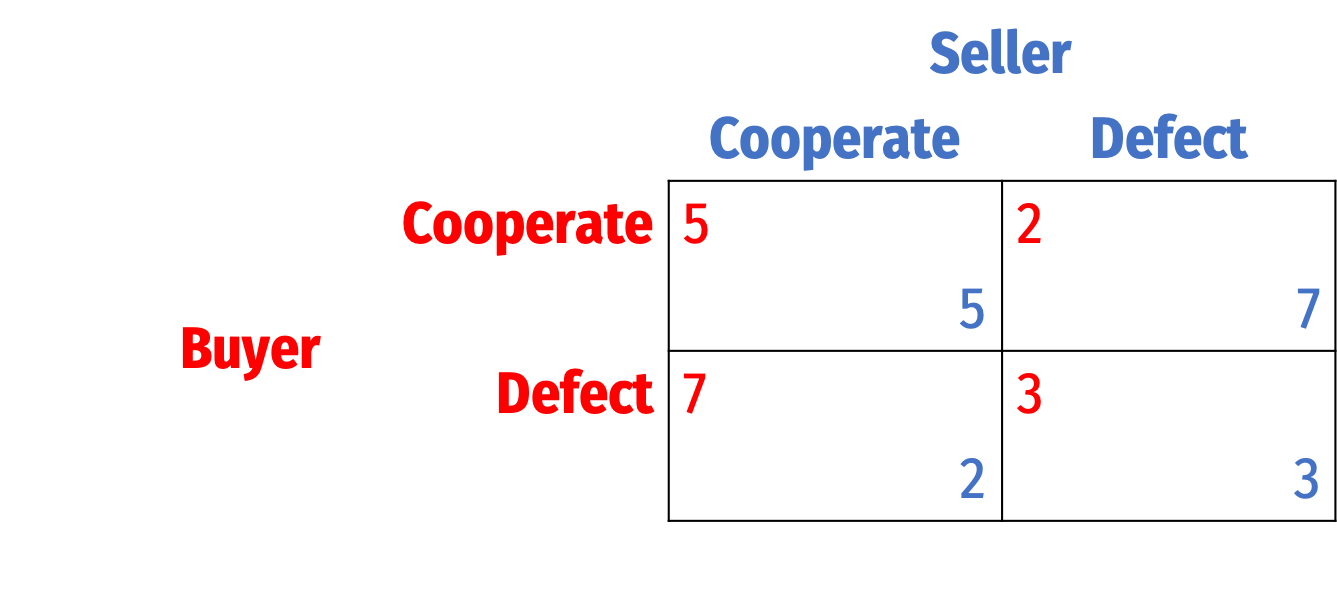

A Repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma

- Essentially firm and customer (which could be another firm) are playing an infinitely repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma

- Cooperate = fulfill contract

- Defect = don’t buy, cheat, renege, hold up, opportunism

A Repeated Prisoners' Dilemma

Consider the “Grim” Trigger strategy: cooperate, but once the other party plays Defect for the first time, Defect for all future turns

Each player will always Cooperate iff:

∞-payoff stream of (C,C)>payoff of 1 (D,C)+∞-payoff stream of (D,D)

- With these payoffs, Cooperating is a SPNE when:

51−δ>7+3δ1−δδ>0.50

- Sufficiently high discount rate/probability of future play constrains incentive to Defect

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“Any profits are competed away in equilibrium by competitive expenditures on fixed (sunk) assets, such as initial specific investments (for example, a sign) with low or zero salvage value if the firm cheats, necessary to enter and obtain this preferred position of collecting the premium stream. These fixed (sunk) costs of supplying credibility of future performance are repaid or covered by future sales on which a premium is earned. In equilibrium,the premium stream is then merely a normal rate of return on the 'reputation,' or 'brand-name' capital created by the firm by these initial expenditures. This brand-name capital, the value of which is highly specific to contract fulfillment by the firm, is analytically equivalent to a forfeitable collateral bond put up by the firm which is anticipated to face an opportunity to take advantage of appropriable quasi rents in specialized assets,” (p.306).

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

Using Market Forces to Enforce Contracts: Reputation

Benjamin Klein

1943-

“We can generally say that the larger the appropriable specialized quasi rents (and therefore the larger the potential short-run gain from opportunistic behavior) and the larger the premium payments necessary to prevent contractual reneging, the more costly this implicit contractual solution will be...the lower the appropriable specialized quasi rents, the more likely that transactors will rely on a contractual relationship rather than common ownership. And conversely, integration by common or joint ownership is more likely, the higher the appropriable specialized quasi rents of the assets involved,” (pp.306-307).

Klein, Benjamin, Robert G Crawford, and Armen A Alchian, 1978, "Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process," Journal of Law and Economics 21(2): 297-326

The Property-Rights Approach to the Firm

Theory of the Firm & Transaction Costs

Ronald H. Coase

(1910-2013)

Economics Nobel 1991

- Coase’s (1937) answer to why there are firms is very general, almost tautological, what about the details?

- Life cycle of firms

- Stigler (1951)

- Nexus of Contract Theory

- Alchian and Demsetz (1972); Jensen and Meckling (1976)

- Asset specificity theory

- Williamson (1975); Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978)

- Property Rights View of the Firm

- Grossman and Hart (1986)

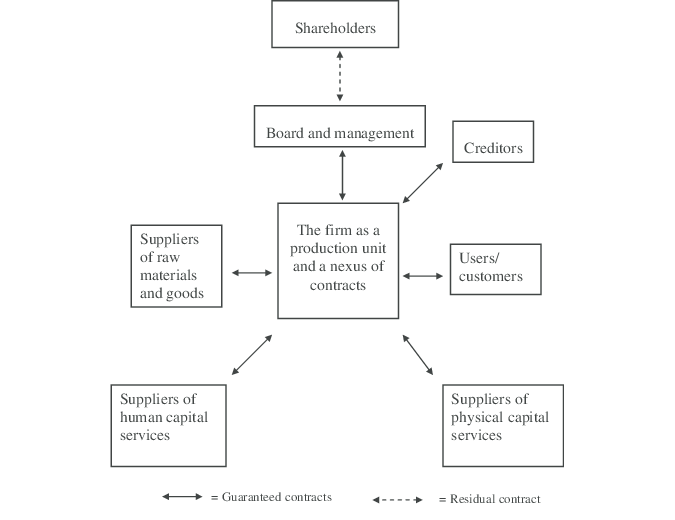

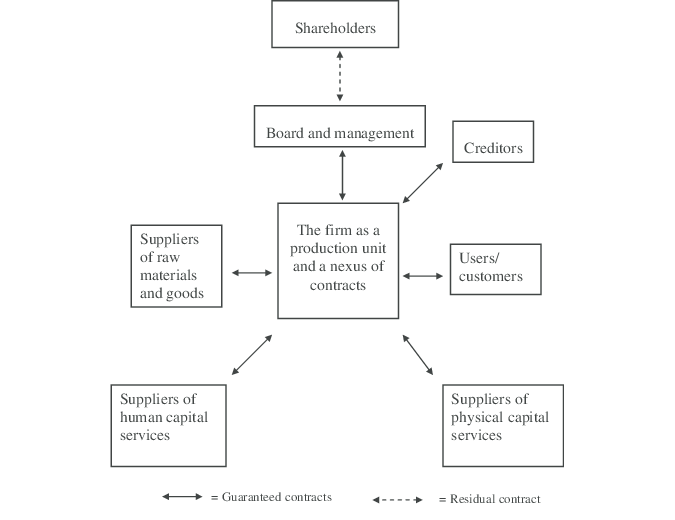

Problems With Other Approaches

- Agency theories of the firm don’t distinguish between contracts within a firm vs. contracts between firms

- The firm is just the legal “nexus” of many contracts between various stakeholders of production

- May be that the “entrepreneur” is the individual that is a party to all contracts

Problems With Other Approaches

- Where is the boundary of the firm? Why would, or would not, firms merge?

- Every contract written within a firm could be written between them

- Why does the information structure or cost of monitoring change when one firm buys out another

- Why does the hold up problem disappear under vertical integration?

- Whether it's one firm or several, they are still using the same physical inputs and assets!

Problems With Other Approaches

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“Klein et al. (1978) and Williamson (1979) added further content by arguing that a contractual relationship between a separately owned buyer and seller will be plagued by opportunistic and inefficient behavior in situations in which there are large amounts of surplus to be divided ex post and in which, because of the impossibility of writing a complete, contingent contract, the ex ante contract does not specify a clear division of this surplus. Such situations in turn are likely to arise when either the buyer or seller must make investments that have a smaller value in a use outside their own relationship than within the relationship (i.e., there exist ‘asset specificities’),” (p.692).

Hart, Oliver and Sanford J Grossman, 1986, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration," Journal of Political Economy 94(4): 691-719

Problems With Other Approaches

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“While these statements help us understand when the costs of contracting between separately owned firms may be high, they do not elucidate what the benefits are of 'organizing the transaction within the firm.' In particular, given that it is difficult to write a complete contract between a buyer and seller and this creates room for opportunistic behavior, the transactions cost-based arguments for integration do not explain how the scope for such behavior changes when one of the self-interested owners becomes an equally self-interested employee of the other owner,” (p.692).

Problems With Other Approaches

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“A second question raised by the transactions cost-based arguments concerns the definition of integration itself. In particular, what does it mean for one firm to be more integrated than another? For example, is a firm that calls its retail force ‘employees’ more integrated than one that calls its retail force ‘independent but exclusive sales agents’?”

“Existing theories cannot answer these questions because they do not give a sufficiently clear definition of integration for its costs and benefits to be assessed...We define integration in terms of the ownership of assets and develop a model to explain when one firm will desire to acquire the assets of another firm,” (p.693).

Hart, Oliver and Sanford J Grossman, 1986, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration," Journal of Political Economy 94(4): 691-719

Ownership As a Response to Uncertainty

“[I]f I am quite sure what kinds of actions my neighbour contemplates, I might be indifferent between his owning the field at the bottom of my garden and my owning it but renting it out for him to graze his horse in. But once I take into account that he may discover some new use for the field that I haven’t yet thought of, but would find objectionable, it will be in my interest to own the field so as to put the use of it under my own control. More generally, ownership of a resource reduces exposure to unexpected events. Property rights are a means of reducing uncertainty without needing to know precisely what the source or nature of the future concern will be,” (Littlechild 1986, p. 35.)

Firm as Owner of Residual Control Rights

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“We define the firm as being composed of the assets (e.g., machines, inventories) that it owns. We present a theory of costly contracts that emphasizes that contractual rights can be of two types: specific rights and residual rights. When it is too costly for one party to specify a long list of the particular rights it desires over another party's assets, it may be optimal for that party to purchase all the rights except those specifically mentioned in the contract. Ownership is the purchase of these residual rights of control.” (p.692).

Hart, Oliver and Sanford J Grossman, 1986, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration," Journal of Political Economy 94(4): 691-719

Firm as Owner of Residual Control Rights

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“We show that there can be harmful effects associated with the wrong allocation of residual rights. In particular, a firm that purchases its supplier, thereby removing residual rights of control from the manager of the supplying company, can distort the manager's incentives sufficiently to make common ownership harmful. We develop a theory of integration based on the attempt of parties in writing a contract to allocate efficiently the residual rights of control between themselves.” (p.692).

Hart, Oliver and Sanford J Grossman, 1986, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration," Journal of Political Economy 94(4): 691-719

Firm as Owner of Residual Control Rights

Oliver Hart

1948-

Economics Nobel 2016

“[W]hen it is too costly for one party to specify a long list of the particular rights it desires over another party's assets, then it may be optimal for the first party to purchase all rights except those specifically mentioned in the contract. Ownership is the purchase of these residual rights of control. Vertical integration is the purchase of the assets of a supplier (or of a purchaser) for the purpose of acquiring the residual rights of control.” (p.716).

Hart, Oliver and Sanford J Grossman, 1986, "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration," Journal of Political Economy 94(4): 691-719

Specific Rights vs. Residual Control Rights

Any contract can specify who has control rights under specific circumstances

- But not possible to do this for all possible circumstances, hence incomplete contracts

Designate a party that has residual control rights to determine what is to be done in an unspecified circumstance

- This right cannot be contracted away

- This is the “owner” of the assets

- We call this, “the firm”

Benefits and Costs of Ownership

Vertical integration = purchasing firm buys right to determine non-specified decisions of purchased firm

Purchased firm (supplier) becomes a division of the purchasing firm

- Purchased firm’s manager may become manager of the division

- Previously held the residual control rights in non-specified circumstances

Benefits and Costs of Ownership

- Benefits of common ownership/vertical integration

- complementary assets owned in common

- economies of scale

- owner (“boss”) controls physical assets to respond to unanticipated circumstances

- can fire the division manager (formerly the purchased-firm’s manager) who causes hold-up problems

Benefits and Costs of Ownership

Costs of common ownership/vertical integration:

Manager of division (formerly independent firm) no longer has residual control rights

- If that manager knows how to better respond than her new boss (manager of purchasing firm), no longer has the residual control rights

- Must convince their boss (puchasing firm manager)

- Division managers thus have less reasons to innovate

Benefits and Costs of Ownership

Thus, it’s very important to allocate ownership correctly!

If you know the Coase Theorem, it’s the same idea!

- Resources tend to flow to those individuals/firms that value them the most, if there are clear and enforceable property rights, and transaction costs are low

- With positive transaction costs, who is given a property right matters for efficiency!