5.1 — Measuring Market Power

ECON 326 • Industrial Organization • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/ioS23

ioS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Measuring Market Power

Recall, market power is the ability of a firm to raise \(p>MC\)

Measures of market concentration

- Concentration Ratios

- Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

Measures of markup pricing

- Lerner Index

The New Empirical Industrial Organization

- importance of econometrics

Market Concentration

Real world markets fall between the polar extremes of our models of perfect competition and monopoly

Concentration measures allow us to gauge the proximity of a market to either extreme

- Easy to compare

- Assist in market regulation

Often \(\in [0,1]\)

- 0 \(\implies\) perfect comepetition

- 1 \(\implies\) monopoly

Market Concentration Measures

- Good measure of market concentration meets:

Principle of Transfer of Sales: a transfer of sales from a small firm to a large firm should increase concentration

Entry condition: entry (exit) of a small firm (holding constant the relative shares of existing firms) should decrease (increase) concentration

Merger condition: merger of 2 or more firms should increase concentration

- Transfer of sales + exit of smallest firm (each raises concentration)

Measuring Market Concentration: Concentration Ratio

- An industry's concentration ratio (CR) adds the market share of the largest \(n\) firms, e.g.

$$CR_n = \sum_{i=1}^n s_i$$

- where \(s_i=\frac{q_i}{Q}\), that firm's fraction of total industry sales

- Common concentration ratios:

- \(CR_4\)

- \(CR_8\)

Market Concentration: The Film Industry

| Rank | Studio | Releases | Tickets | Sales | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Walt Disney | 13 | 410,812,035 | $3,742,497,656 | 0.3315 |

| 2 | Warner Bros. | 43 | 172,395,261 | $1,570,520,862 | 0.1391 |

| 3 | Sony Pictures | 24 | 150,913,744 | $1,374,824,330 | 0.1218 |

| 4 | Universal | 26 | 143,128,035 | $1,303,896,396 | 0.1155 |

| 5 | Lionsgate | 21 | 87,579,701 | $797,851,162 | 0.0707 |

| 6 | Paramount | 11 | 61,899,898 | $563,908,126 | 0.0499 |

| 7 | 20thC. Fox | 13 | 54,024,024 | $492,158,921 | 0.0436 |

Measuring Market Concentration: Concentration Ratio

| Rank | Studio | Share |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Walt Disney | 0.3315 |

| 2 | Warner Bros. | 0.1391 |

| 3 | Sony Pictures | 0.1218 |

| 4 | Universal | 0.1155 |

| 5 | Lionsgate | 0.0707 |

| 6 | Paramount | 0.0499 |

| 7 | 20thC. Fox | 0.0436 |

$$CR_2 = \sum^2_{i=1} =0.4706$$

$$CR_3 = \sum^3_{i=1} = 0.5924$$

$$CR_4 = \sum^4_{i=1} = 0.7079$$

$$CR_7 = \sum^7_{i=1} = 0.8721$$

Measuring Market Concentration: Concentration Ratio

Problems with CR's:

\(n\) is arbitrarily chosen (2? 4? 8?)

Does not follow transfer of sales principle

- e.g. Firm 1 gaining 0.20 and Firm 3 and 4 each losing 0.10 doesn't change \(CR_4\)!

No weighting by size

Measuring Market Concentration: Concentration Ratio

Example: Take industry A with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.60 |

| 2 | 0.10 |

| 3 | 0.05 |

| 4 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 0.05 |

$$CR_4 = 0.80$$

Example: Take industry B with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 0.20 |

| 3 | 0.20 |

| 4 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 0.20 |

$$CR_4 = 0.80$$

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

- Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI): measures the sum of the squares of market share of all firms in an industry

$$HHI=\sum^n_{i=1} s_i^2$$

- Where \(s_i=\frac{q_i}{Q}\)

- Why squared? Gives more weight to firms with more market share (unlike CR)

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

\(HHI \in[0,1]\)

Monopoly \(HHI = 1\)

Perfect competition: \(HHI = \frac{1}{n} \rightarrow 0\)

- \(n\) firms of equal size

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

Example: Take industry A with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.60 |

| 2 | 0.10 |

| 3 | 0.05 |

| 4 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 0.05 |

$$CR_4 = 0.80$$

$$\begin{align*}HHI &= 0.60^2+0.10^2+0.05^2+0.05^2+0.05^2\\ &= 0.3775\\ \end{align*}$$

Example: Take industry B with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 0.20 |

| 3 | 0.20 |

| 4 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 0.20 |

$$CR_4 = 0.80$$

$$\begin{align*} HHI &= 0.20^2+0.20^2+0.20^2+0.20^2+0.20^2 \\ &= 0.20 = 1/5 \\ \end{align*}$$

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

- Equivalent number \(n^*\), number of equal-sized firms in a hypothetical market that would give rise to the same HHI as observed

$$n^* = \frac{1}{HHI}$$

\(HHI=0.2 \implies \frac{1}{HHI} = 5\) equal sized firms

\(HHI=0.8 \implies \frac{1}{HHI} = 1.25\) equal sized firms

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

$$HHI \text{ (in percentages)} = 10,000 \sum^n_{i=1} s_i^2$$

HHI is often measured in percentage form by U.S. antitrust authorities

- Market shares as percentages instead of decimals

Here, \(HHI \in [0, 10,000]\)

- Monopoly: HHI = 10,000, 1 firm with 100% market share \(\implies 100^2 = 10,000\)

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

Example: Take industry A with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 60% |

| 2 | 10% |

| 3 | 5% |

| 4 | 5% |

| 5 | 5% |

$$\begin{align*} HHI &= 60^2+10^2+5^2+5^2+5^2\\ &= 3,775\\ \end{align*}$$

Example: Take industry B with

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 20% |

| 2 | 20% |

| 3 | 20% |

| 4 | 20% |

| 5 | 20% |

$$\begin{align*} HHI &= 20^2+20^2+20^2+20^2+20^2 \\ &= 2,000 \bigg(=\frac{10,000}{5} \bigg) \\ \end{align*}$$

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

- If two firms, with market share \(s_1\) and \(s_2\), merge, HHI increases by \((s_1+s_2)^2-s_1^2-s_2^2=2s_1s_2\)

Measuring Market Concentration: HHI

Before Firms 1 and 2 Merge

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 60% |

| 2 | 10% |

| 3 | 5% |

| 4 | 5% |

| 5 | 5% |

$$HHI_{pre} = 3,775$$

After Firms 1 and 2 Merge

| Firm | Market Share |

|---|---|

| 1 | 70% |

| 2 | 5% |

| 3 | 5% |

| 4 | 5% |

$$HHI_{post} = 4,975$$

$$\Delta HHI = 1,200 = (2 \times 60 \times 10)$$

Measuring Markups

Recall: Lerner Index and Inverse Elasticity Rule

- Lerner Index measures market power as % of firm's price that is markup above \(MC(q)\)

$$L=\frac{p-MC(q)}{p} = -\frac{1}{\epsilon_D}$$

- i.e. \(L \times 100\%\) of firm's price is markup

- \(L=0 \implies\) perfect competition

- (since \(P=MC)\)

- As \(L\rightarrow 1 \implies\) more market power

Recall: Lerner Index and Inverse Elasticity Rule

$$L = \frac{p-MC}{p} = -\frac{1}{\epsilon_D}$$

This simple formula only works for a monopoly \((n=1)\)!

Lerner Index and Cournot Theorem

- Consider Cournot competition between \(n\) firms with identical costs \(MC_i\), the Lerner index actually becomes:

$$L = \frac{p-MC_i}{p} = -\frac{s_i}{\epsilon_D}$$

Where \(s_i = \frac{q_i}{Q}\)

- Note monopoly is special case where \(\frac{q_i}{Q}=1\)!

Lerner Index and Cournot Theorem

$$L = \frac{p-MC_i}{p} = -\frac{s_i}{\epsilon_D}$$

Alternatively, since \(s_i=\frac{1}{n}\):

$$L = \frac{p-MC_i}{p} = -\frac{1}{n\epsilon_D}$$

Lerner Index and Cournot Theorem

$$L = \frac{p-MC_i}{p} = -\frac{s_i}{\epsilon_D} = -\frac{1}{n\epsilon_D}$$

Market power is inversely related to price elasticity of demand

- Larger (smaller) \(\epsilon\), smaller (larger) markup \(p-MC\)

Market power is inversely related to the number of competitors

- Greater number of competitors \(\uparrow n\), smaller \(s_i\), and hence less market power

Lerner Index and Cournot Theorem

$$\sum^n_{i=1} s_i\frac{p-MC_i}{p} = -\frac{\sum^n_{i=1}s_i^2}{\epsilon_D} = -\frac{HHI}{\epsilon_D}$$

Can add up all of the market-share-weighted markups

Equivalent to HHI divided by price elasticity

Recall we saw implication of Cournot competition

Can use HHI to measure implications about firm conduct

Some Estimates

Some Estimates

DOJ on HHI

“The agencies generally consider markets in which the HHI is between 1,500 and 2,500 points to be moderately concentrated, and consider markets in which the HHI is in excess of 2,500 points to be highly concentrated.

“Transactions that increase the HHI by more than 200 points in highly concentrated markets are presumed likely to enhance market power under the Horizontal Merger Guidelines issued by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission.”

Department of Justice, 2017, HHI

Market Definition

Shortcomings of Market Concentration Measures

Measures crucially rest on the definition of the industry or market

Product dimension: which products do consumers see as substitutes?

Geographic dimension: where are firms that produce similar products? (supply-side substitutes)

Differentiated products \(\implies\) imperfect substitutes

Often include all products that have significant cross-price elasticity of demand

Industry Classification

NAICS used by statistical agencies such as the U.S. Census to classify industries

Places production into one of 1,004 4-digit industries, defined nationally

Do not accurately correspond to economic markets

- May include some products clearly not substitutes, or leave out some products that clearly are substitutes

- Hence, should not be assumed to match properly with HHI measures

Market Definition

“The Agencies employ the hypothetical monopolist test to evaluate whether groups of products in candidate markets are sufficiently broad to constitute relevant antitrust markets. The Agencies use the hypothetical monopolist test to identify a set of products that are reasonably interchangeable with a product sold by one of the merging firms.”

Department of Justice, 2010, Horizontal Merger Guidlines

Market Definition

“The hypothetical monopolist test requires that a product market contain enough substitute products so that it could be subject to post-merger exercise of market power significantly exceeding that existing absent the merger. Specifically, the test requires that a hypothetical profit-maximizing firm, not subject to price regulation, that was the only present and future seller of those products (‘hypothetical monopolist’) likely would impose at least a small but significant and non-transitory increase in price ‘SSNIP’) on at least one product in the market, including at least one product sold by one of the merging firms. For the purpose of analyzing this issue, the terms of sale of products outside the candidate market are held constant. The SSNIP is employed solely as a methodological tool for performing the hypothetical monopolist test; it is not a tolerance level for price increases resulting from a merger.”

Department of Justice, 2010, Horizontal Merger Guidlines

Market Definition

Starting in 1982, Department of Justice began defining an “antitrust market” to solve some of these problems

Determined by a “hypothetical monopolist test”: a set of products and a geographic area where a single seller would be able to exert significant market power (raise price)

Specifically, a “small but significant and nontransitory increase in price” (SSNIP) of 5% for 1 year

Courts regularly talk about cross-price elasticities of demand in antitrust cases!

The Courts on Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand

“For every product substitutes exist. But a relevant market cannot meaningfully encompass that infinite a range. The circle must be drawn narrowly to exclude any other product to which, within reasonable variations in price, only a limited number of buyers will turn; in technical terms, products whose ‘cross-elasticities of demand’ are small,” Times-Picayune Publishing v. United States, 345 U.S. 594 at 621 n. 31 (1953)

“Every manufacturer is the sole producer of the particular commodity it makes but its control in the above sense of the relevant market depends on the availability of alternative commodities for buyers: i.e., whether there is a cross-elasticity of demand between cellophane and the other wrappings,” U.S. v. E. I. du Pont de Nemours &. Co., 351 U.S. 377 (1956))

“Cross-price elasticity is a more useful tool than own-price elasticity in defining a relevant antitrust market. Cross-price elasticity estimates tell one where the lost sales will go when the price is raised, while own-price elasticity estimates simply tell one that a price increase would cause a decline in volume,” New York v. Kraft General Foods, 926 F. Supp. 321 (1995)

Can We Measure Market Power from Prices?

Can We Measure Market Power from Prices?

- Can we tell a collusive market from a competitive one?

$$L=\frac{p-MC}{p}=-\frac{1}{\epsilon_D}$$

We can only observe \(p\)'s and \(q\)'s

Could be Bertrand price competition, firms setting \(p=MC\)

- Or it could be a cartel splitting monopoly profits by fixing the price

Data problems: we never know MC!

Empirical Challenge: Identifying Power from Prices

$$L=\frac{p-MC}{p}$$

Imagine we observe a market with \(n\) sellers all charging price \(p\) and selling quantity \(q\)

Two possible explanations:

- The market is competitive, and all firms are charging \(p=MC\)

- The market is collusive, and all firms are marking up \(p>MC\)

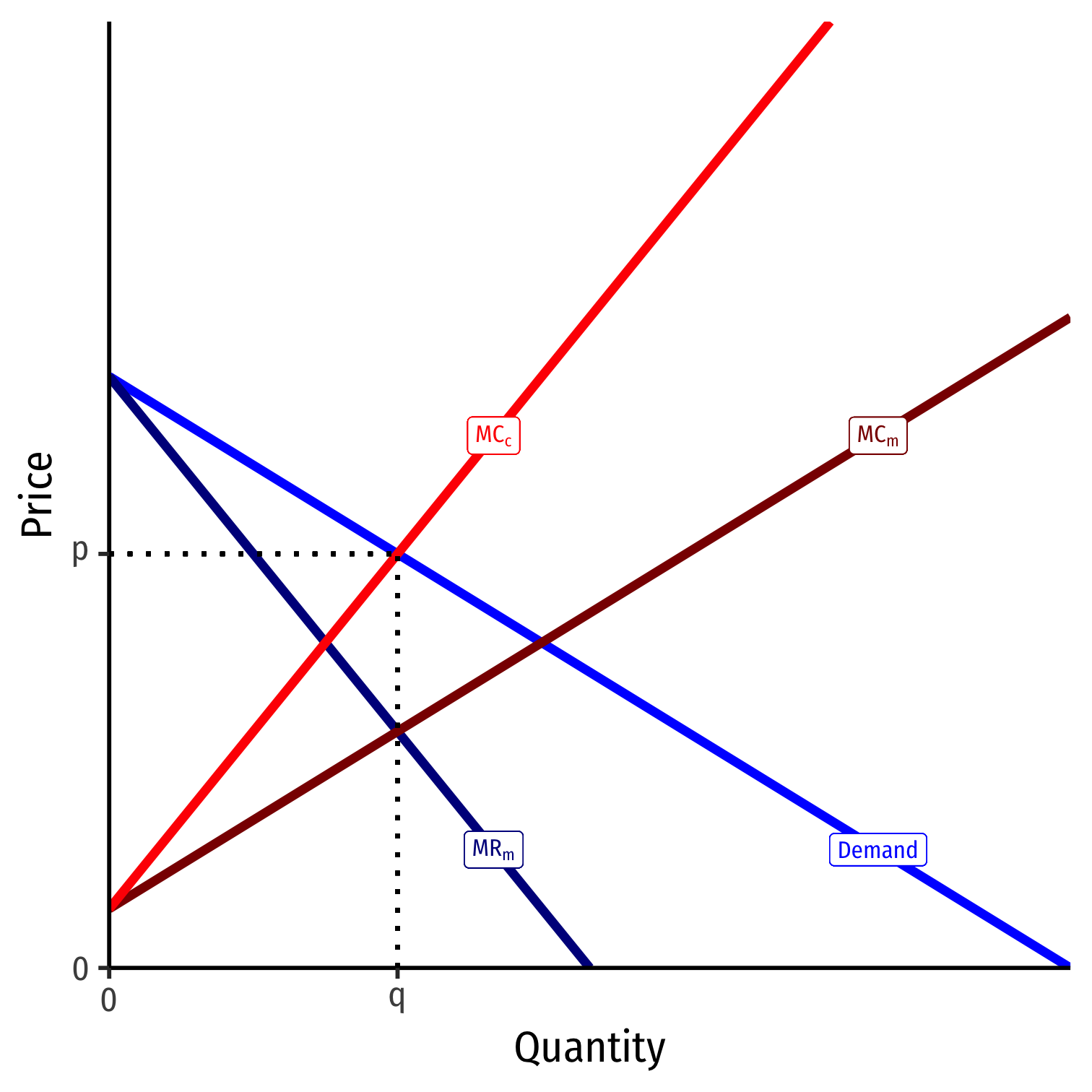

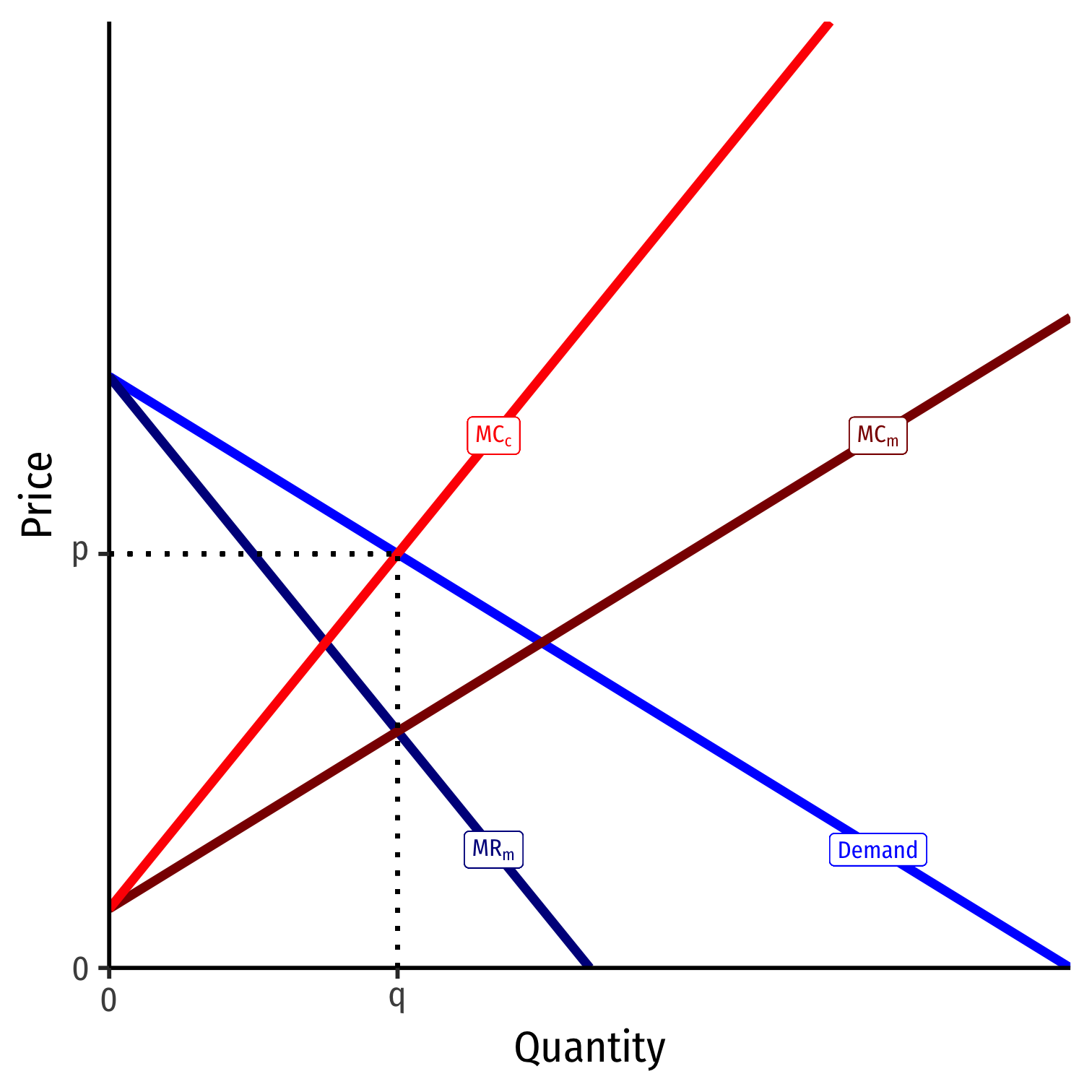

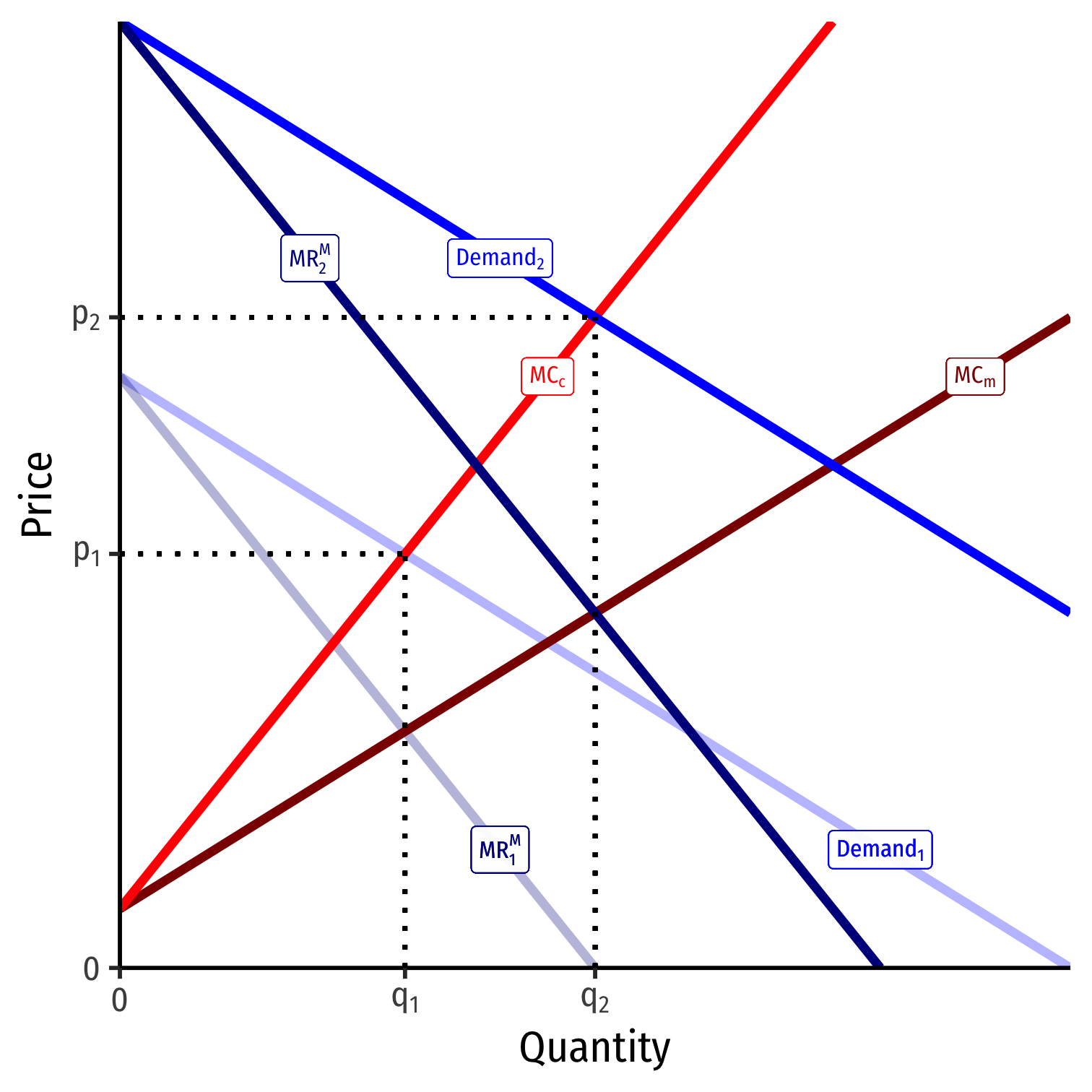

Empirical Challenge: Identifying Power from Prices

- We can rationalize each explanation as follows:

Competitive firms have (higher) \(\color{red}{MC_c}\) and are setting it equal to demand to get \(p\) at quantity \(q\)

Cartel has (lower) \(\color{darkred}{MC_m}\) at quantity \(q\), sets it equal to \(MR_M=m\), marking price up to \(p\)

Empirical Challenge: Identifying Power from Prices

- What if Demand shifts to Demand \(_2\)? Same problem!

Competitive firms set \(\color{red}{MC_c}\) equal to new demand 2 to get \(p_2\) at \(q_2\)

Cartel sets \(\color{darkred}{MC_M}\) equal to new \(MR_2^M\) at \(q_2\), mark up to \(p_2\)

- Changes in demand aren’t sufficient to identify market power

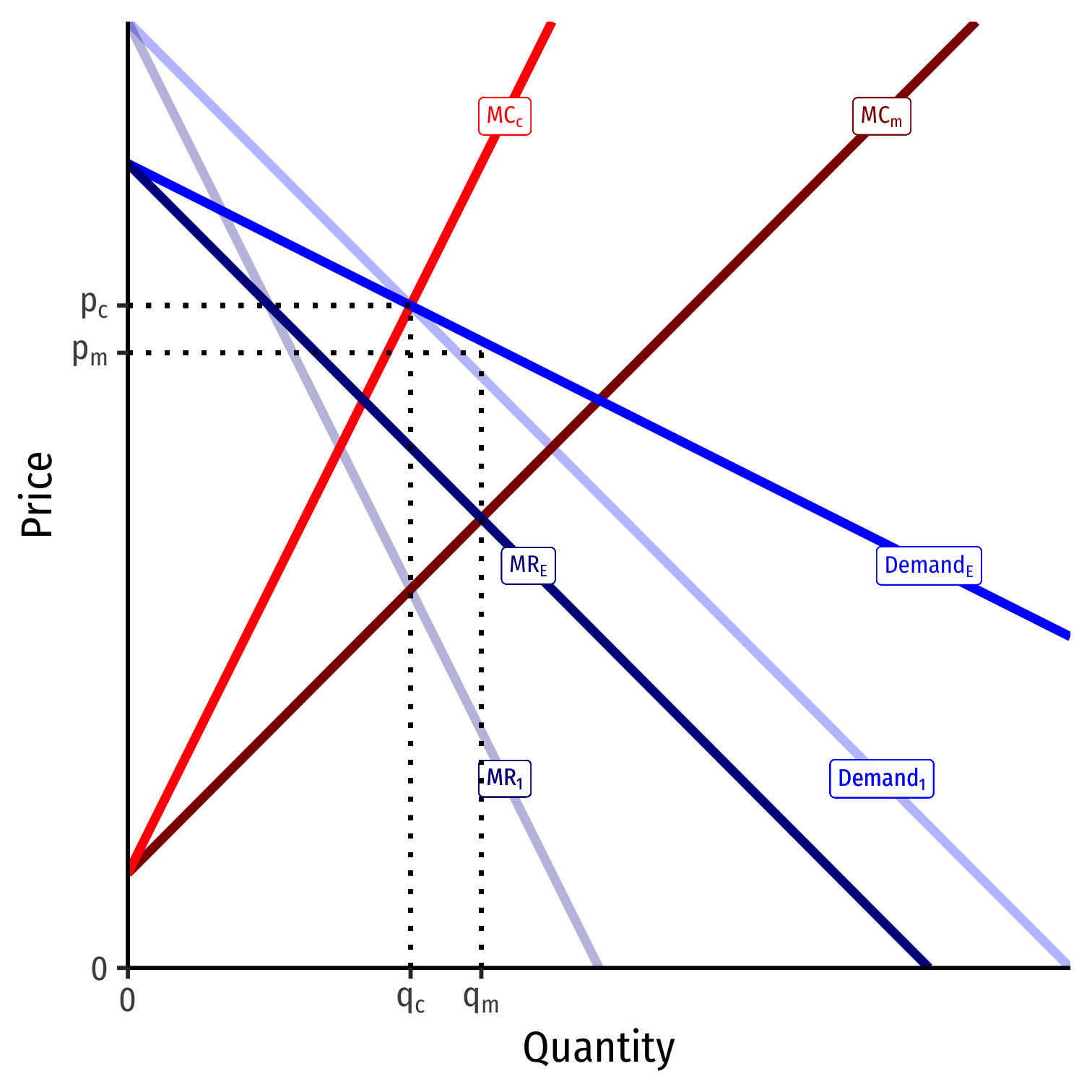

Empirical Challenge: Identifying Power from Prices

Potential solution famously identified by Bresnahan (1982):

If demand rotates through a price (i.e. becomes more elastic without changing equilibrium price)

Competitive firms don't change \(p\) or \(q\) \((MC_c\) still intersects Demand at same point!)

Cartel changes to \(p_m\) and \(q_m\) since \(MR\) will change (and hence, intersection of \(MC_m=MR)\)

"Translations [i.e. shifting] of the demand curve will always trace out a supply relation. Rotations of the demand curve around the equilibrium point will reveal the degree of market power," (Bresnahan 1982)

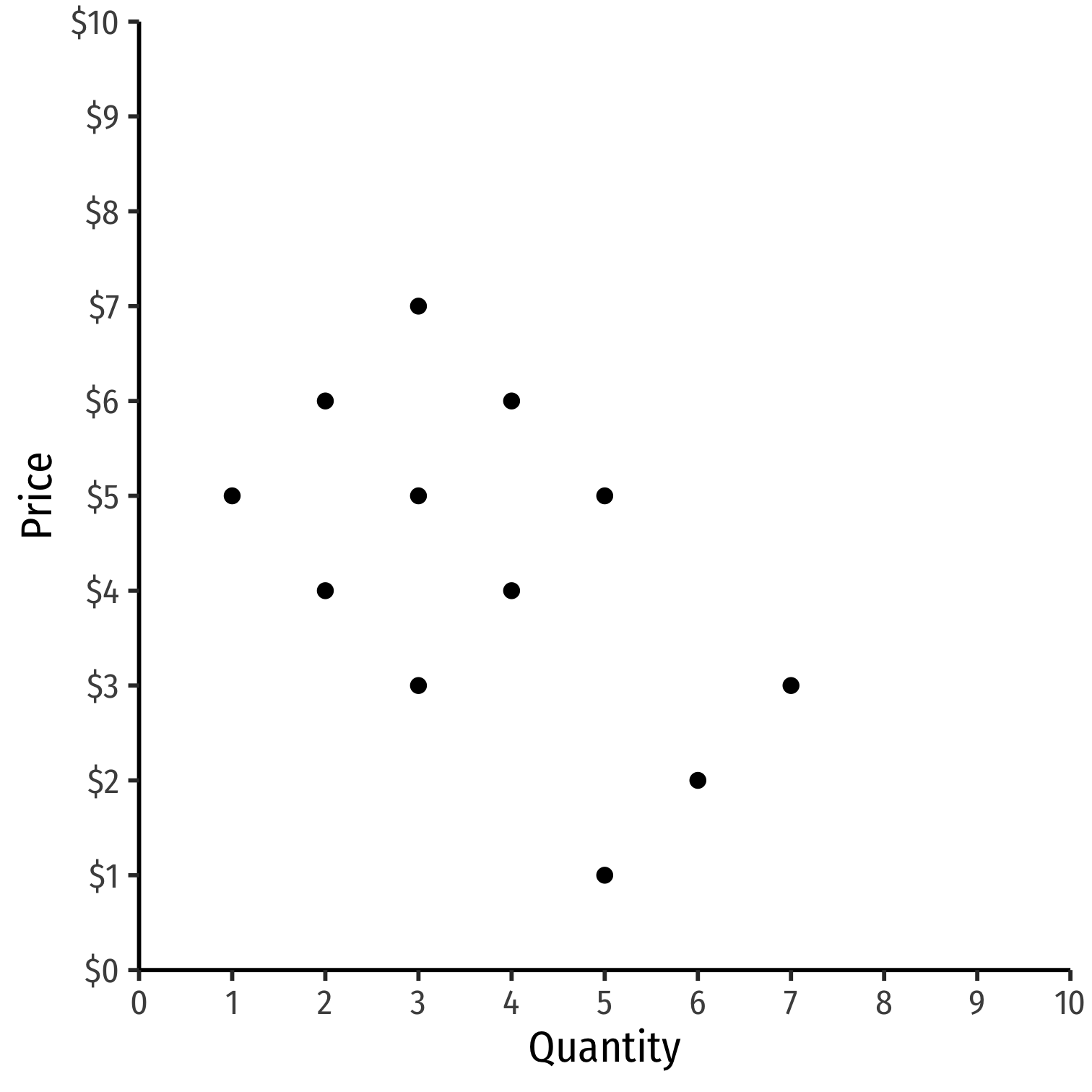

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

Suppose we have price and consumption data for an industry

Fairly easy to acquire

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

Suppose we have price and consumption data for an industry

Fairly easy to acquire

Why can't we estimate the demand curve with a simple regression here?

$$\ln(Quantity_{it}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \ln(Price_{it}) + \varepsilon_{it}$$

- With natural logs, \(\beta_1\) is the price elasticity of Demand

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

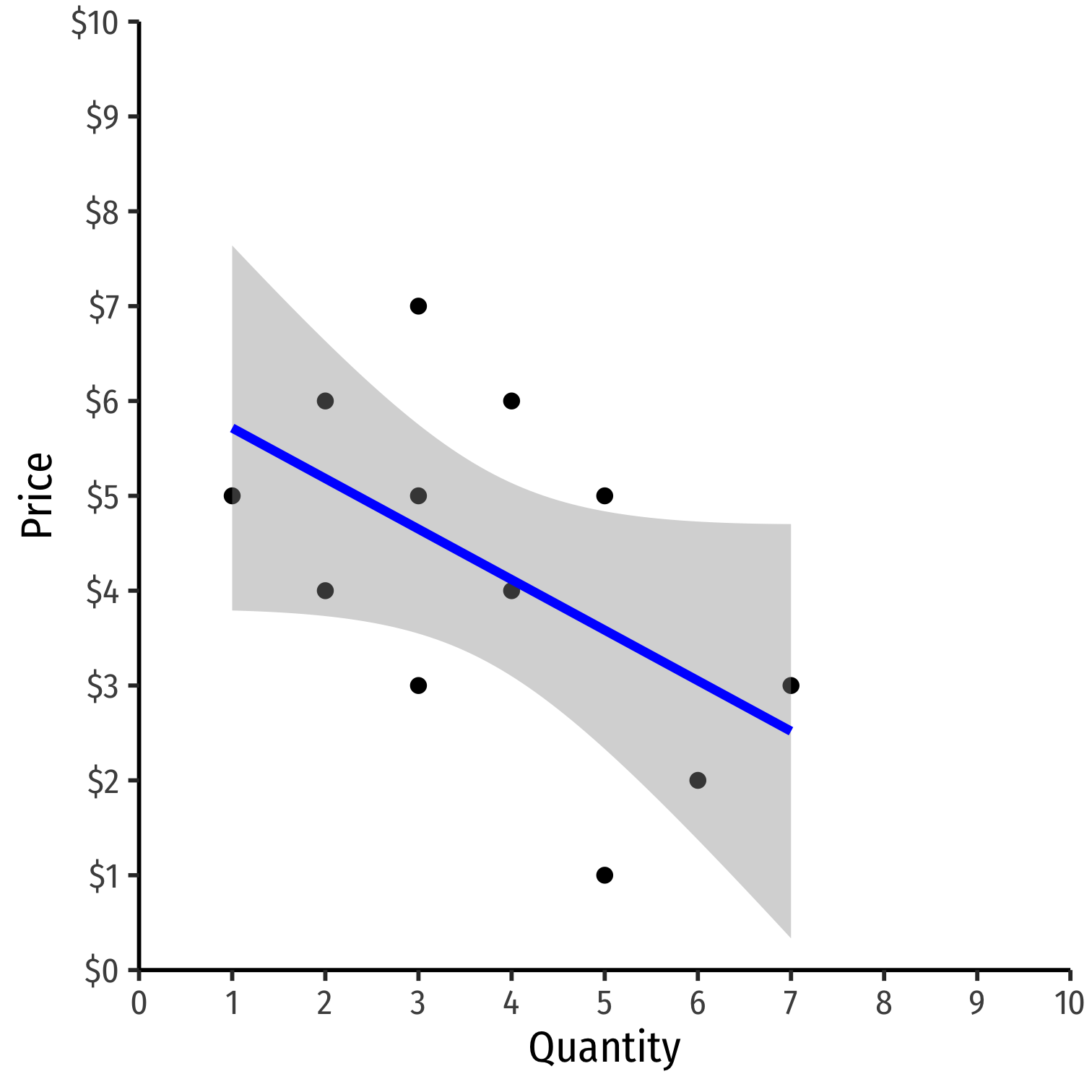

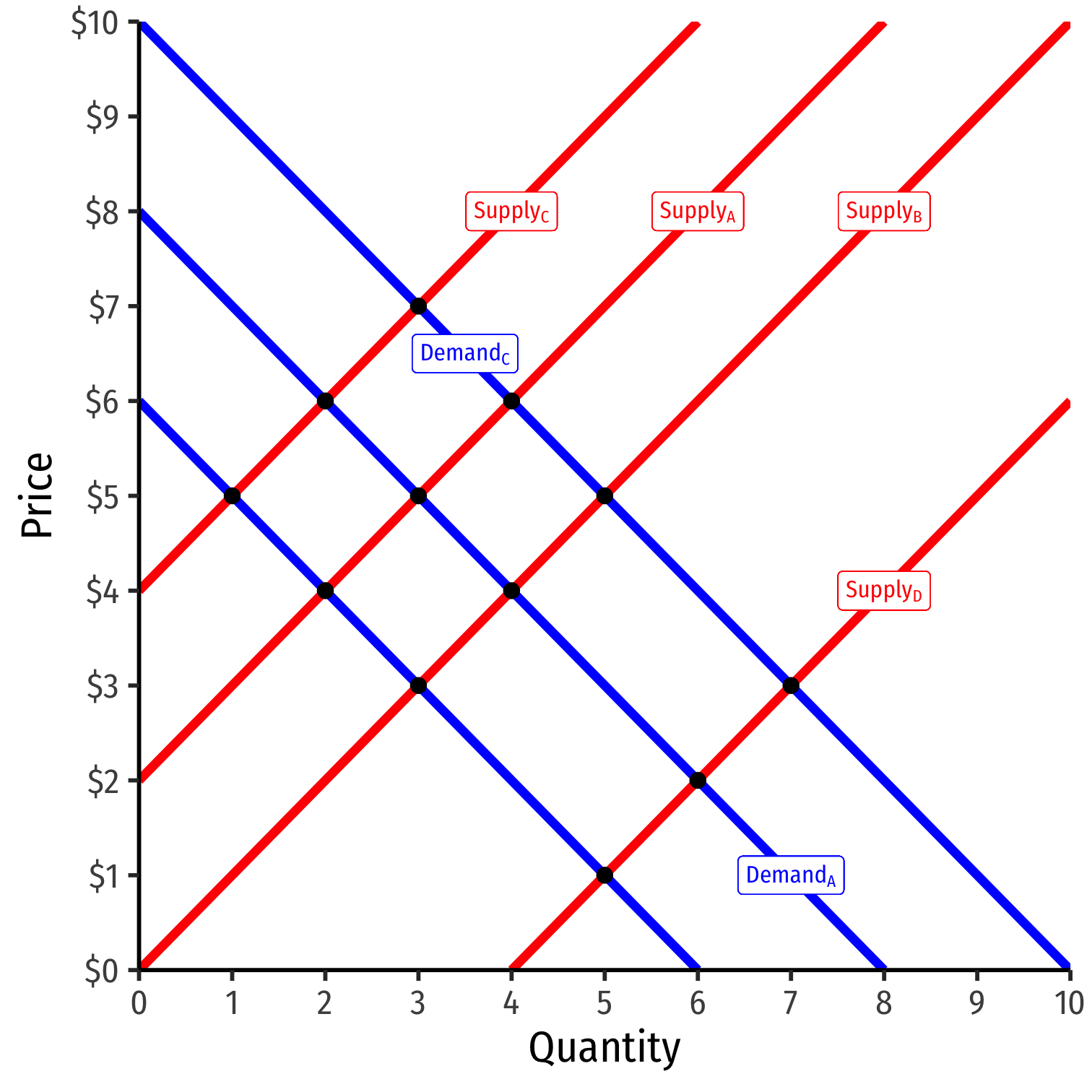

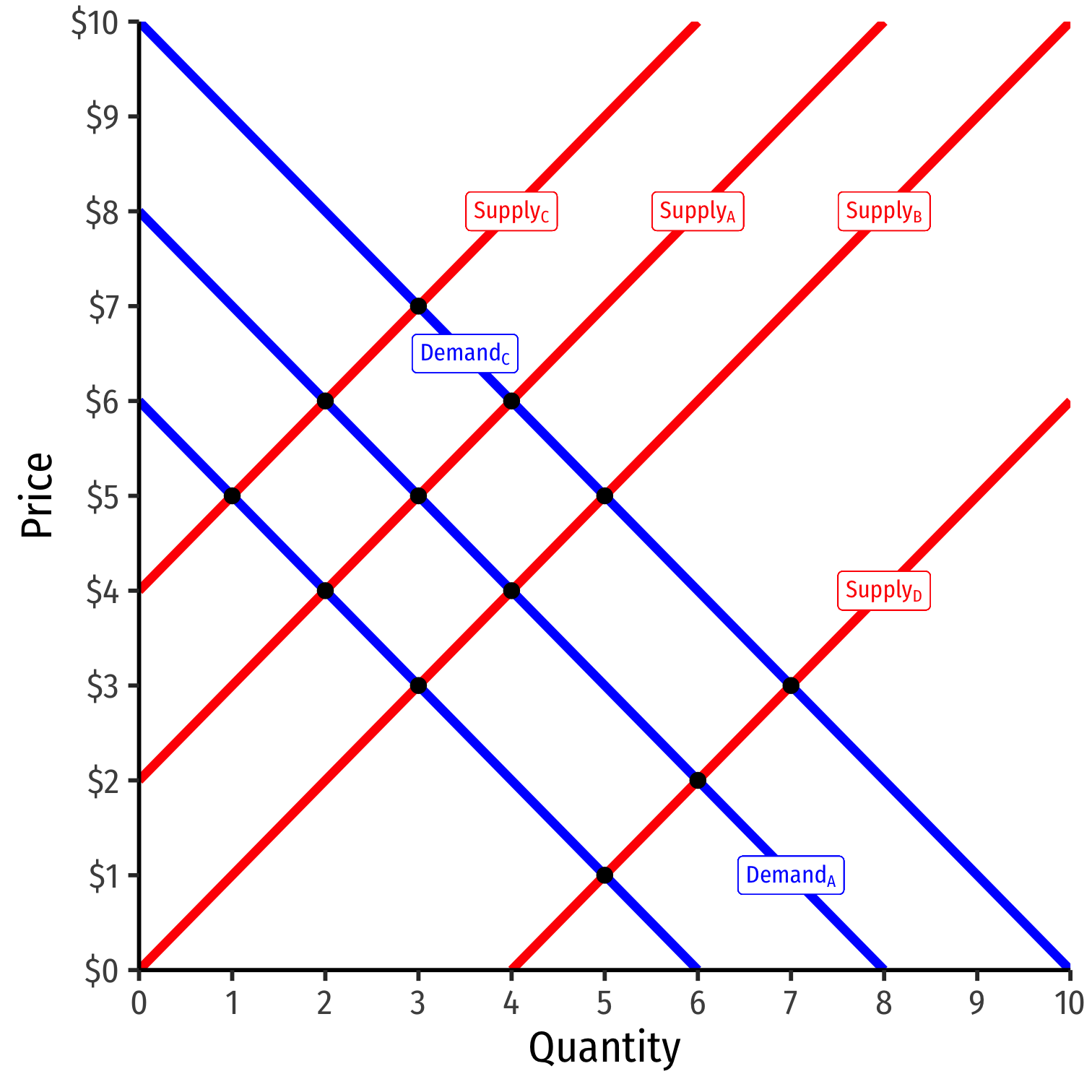

What we are actually looking at are a series of equilibrium \((Q^*,P^*)\) points!

Result of many demand and supply curve shifts & intersections!

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

- Structural equation model of demand and of supply:

$$\begin{align*} \color{blue}{Q_D} & \color{blue}{= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 P + \alpha_2 M + u_D} \\ \color{red}{Q_S} & \color{red}{= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P + \beta_2 C+ u_S} \\ \end{align*}$$

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

- Structural equation model of demand and of supply:

$$\begin{align*} \color{blue}{Q_D} & \color{blue}{= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 P + \alpha_2 M + u_D} \\ \color{red}{Q_S} & \color{red}{= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P + \beta_2 C+ u_S} \\ \end{align*}$$

- \(\alpha\)'s and \(\beta\)'s are parameters (to be estimated), \(u\)'s are unobserved error terms

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

- Structural equation model of demand and of supply:

$$\begin{align*} \color{blue}{Q_D} & \color{blue}{= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 P + \alpha_2 M + u_D} \\ \color{red}{Q_S} & \color{red}{= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P + \beta_2 C+ u_S} \\ \end{align*}$$

\(\alpha\)'s and \(\beta\)'s are parameters (to be estimated), \(u\)'s are unobserved error terms

\(P\) is price

- Notice \(P\) simultaneously determines \(\color{blue}{Q_D}\) and \(\color{red}{Q_S}\)!

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

- Structural equation model of demand and of supply:

$$\begin{align*} \color{blue}{Q_D} & \color{blue}{= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 P + \alpha_2 M + u_D} \\ \color{red}{Q_S} & \color{red}{= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P + \beta_2 C+ u_S} \\ \end{align*}$$

\(\alpha\)'s and \(\beta\)'s are parameters (to be estimated), \(u\)'s are unobserved error terms

\(P\) is price

- Notice \(P\) simultaneously determines \(\color{blue}{Q_D}\) and \(\color{red}{Q_S}\)!

\(\color{blue}{M}\) are variables that shift demand (i.e. income, prices of other goods, etc)

- \(\color{red}{C}\) are variables that shift supply (i.e. costs, etc)

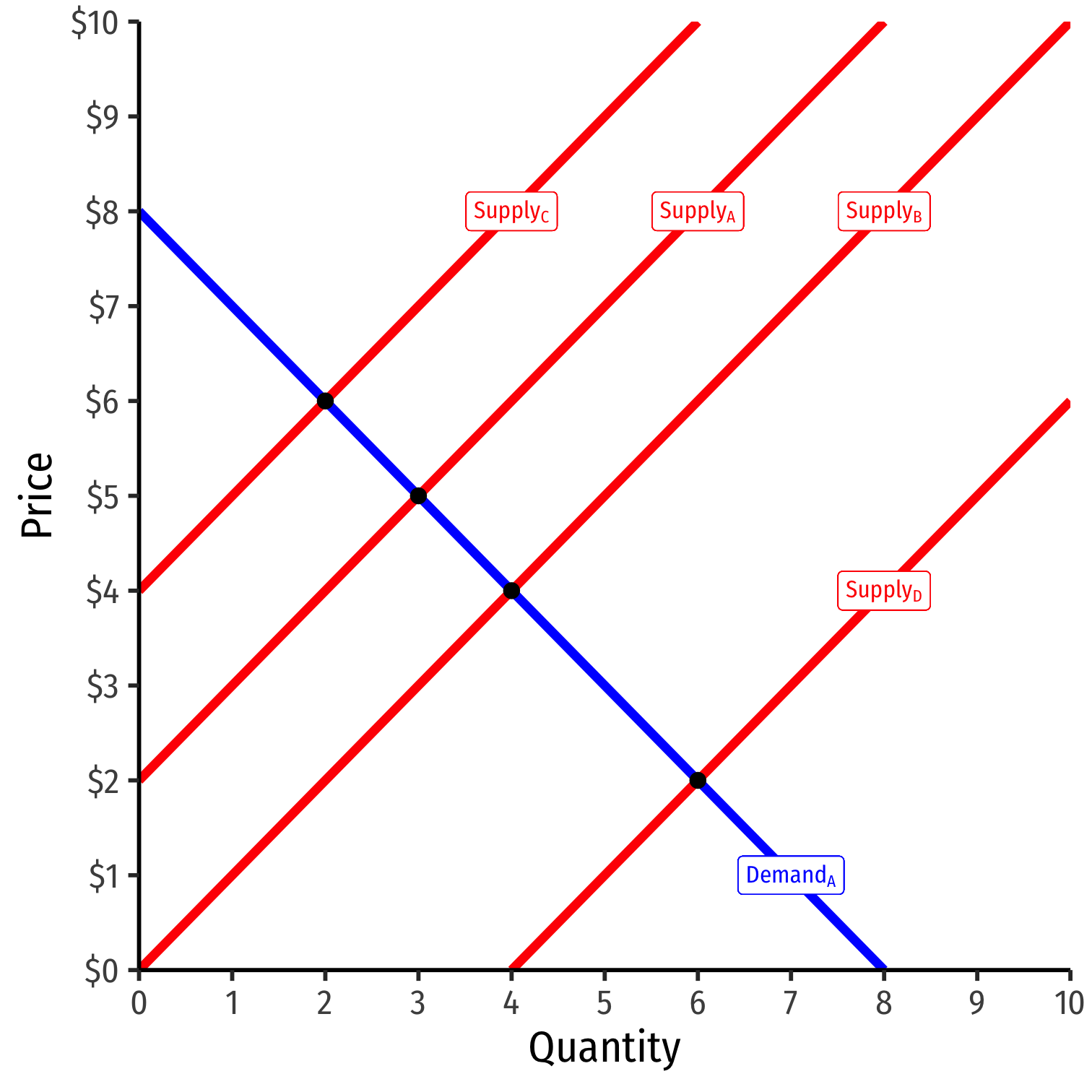

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

$$\color{blue}{Q_D = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 P + \alpha_2 M + u_D}$$

Why can't we just estimate price elasticity of demand \((\alpha_1)\) with the demand equation?

P is partially a function of quantity supplied!

Empirical Challenges: Estimating Demand & Elasticity

Instrumental variables and 2-stage least squares techniques to identify demand relationship

Often use some supply shifter (like cost changes, \(C)\) correlated with price \(\color{blue}{P}\), but not correlated with \(\color{blue}{u_D}\)

Essentially: traces out unique demand relationship by allowing supply to vary & shift

Then, can estimate demand elasticity \(\beta_1\)

The New Empirial Industrial Organization

See an example of this in my econometrics course

“New Empirical Industrial Organization” (NEIO)

Focus on data, econometrics, machine learning, merger simulations

Private businesses, law firms, consulting firms, and government agencies (FTC, DOJ) hire economists trained in econometrics and IO for antitrust research, expert testimony